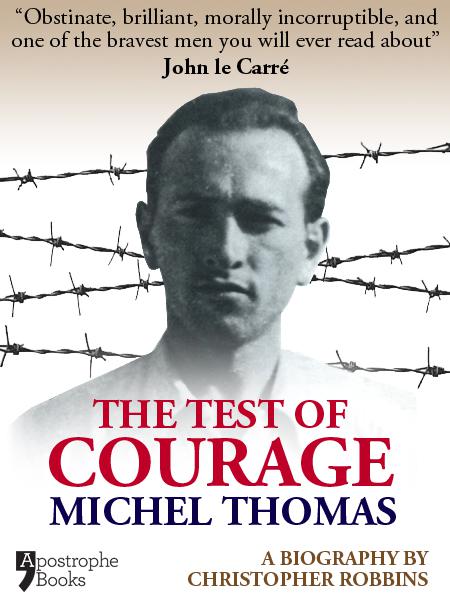

The Test of Courage: (A Biography of) Michel Thomas

Read The Test of Courage: (A Biography of) Michel Thomas Online

Authors: Christopher Robbins

In memory of Freida and Idessa, and of Georgina

“Often the test of courage is not to die but to live.”

Vittorio Alfieri (1749-1803)

Contents

I - ‘Everything seems hopeless: what are we to do?’

Prologue

As a natural sceptic I would not have been inclined to believe the biography of Michel Thomas if I had not been told about him by someone whose own wartime experiences were beyond doubt. My friend spoke of a man who had endured hell in the early years of the war through internment in concentration and deportation camps in France, but who had refused to become a victim. He had escaped to fight with the Résistance, suffered further imprisonment and torture, and then fought with the US Army. Later, in the years directly after the war, he hunted Nazis and war criminals as a special agent with American Counter Intelligence, posing in one elaborate operation as a high-ranking Nazi intelligence officer. It was a life that seemed as fascinating as it was unlikely.

And then there was Michel Thomas’ equally improbable post-war reputation as one of the world’s great language masters with the ability to teach students in a matter of days. His celebrity clients included people as diverse as Woody Allen, Bob Dylan and Emma Thompson, yet his main interest was reforming the education system itself, and helping disadvantaged children. People spoke of miracles and magic, and his power to hypnotise, read minds and block pain. It was also said, by one of the great secret service cryptographers of the Second World War, that it was impossible to lie to him.

‘You should talk to Michel,’ my friend said. ‘You’ll find him interesting.’

Michel Thomas proved to be a quietly spoken, soberly-suited gentleman, with the old-fashioned, courtly manners of another age, but even during our first encounter, when the conversation was superficial and general, I became aware that I was in the presence of a highly unusual and unique individual.

He exuded intensity and warmth and I received an impression of immense self-confidence and inner strength that was almost tangible. In time, I would come to understand that beneath the calm exterior and easy charm, a constant anger burned white hot, and that Michel was as tough as anyone I had ever met, a man of steel. But after that first, brief meeting I left charged with an inexplicable energy and enthusiasm. True to his reputation, he had cast a spell of sorts.

We began to meet often whenever he was in London, and I sought him out in New York and Los Angeles. He seemed perpetually on the move and forever at work. We had long lunches that lasted until evening, and dinners that stretched into the early hours of the morning. I proposed chronicling his life story and Michel agreed. We came to an understanding whereby he would answer questions about all areas of his life, and I would be free to write the book in my own way, interview whomever I wished, and pursue any and every independent avenue of research. Michel would then have access to the final manuscript to correct errors of fact, and the editing process would be one of mutual consent.

The result was hundreds of hours of taped interviews that became the foundation of this book. Few men alive can have witnessed so much raw history, and Michel’s experiences have been kept alive by a unique form of emotional memory-consciously developed as a child - that relives rather than recalls past events. Memory of such power and immediacy can be a painful gift, and it has endowed Michel with what he describes as, ‘A past that does not pass.’

But memory, however powerful, inevitably distorts and telescopes time. Events are subconsciously ordered and re-arranged, and even if the past is held on to and not allowed to pass, it is edited and coloured and becomes blurred. Michel’s personal history is bolstered and verified by a suitcase full of personal papers that is never far from his side. In addition I unearthed a wealth of documents that fixed the principal dates and events of every period of his life. These came from a wide range of sources: French government and court records giving the dates of internment and transportation, family letters, official accreditation cards from the Résistance, ID cards from the US Army and Counter Intelligence, reports written at the time by combat and intelligence colleagues, and numerous interviews with contemporaries from the various periods of Michel’s life. There were also finds in the US National Archives and Army records.

The more I learned about Michel, the more interested I became in the connection between the experiences of his life and the revolutionary system of teaching languages that has evolved from it. I interviewed university professors and academics in an attempt to understand the technique, and spoke to scores of students - ranging from ambassadors and movie stars, to businessmen, nuns and schoolchildren - to confirm the results.

For me, the experience has been both an education and a remarkable journey. To follow the life of Michel Thomas is to be handed a human route map to some of the most disturbing history of the twentieth century, and to be guided along its treacherous roads by an eyewitness with a truly original mind. ‘It seems from what I know that I am the only living survivor of many of these events. I have never pushed memory away. I have nurtured, not buried it. If I am the only survivor I owe it to those who have died to remind people of the facts. I am a witness.’

I - ‘Everything seems hopeless: what are we to do?’

On a rainy night in Manhattan, more than fifty years after the end of the Second World War, Michel Thomas pulled a packet of letters from the safe in his apartment and placed them on a writing desk. It was late, and he was alone. The study was dimly lit so he switched on a lamp beside his chair, sat down and pulled the letters towards him. He spread them out in a fan, a dozen dog-eared airmail envelopes faded with age. There were two sets of handwriting, both distinctly feminine versions of an old-fashioned continental copperplate, and a single envelope that had been inexpertly typed on an antiquated machine.

The letters dated from just after the outbreak of war in Europe and were among Michel’s most prized possessions. He had lost count of the number of times he had taken them from their battered, black cardboard file and set them down in front of him. It was a ritual: he picked up the letters and held them, turned them over again and again, laid them back down and stared at them. He had removed the fragile airmail sheets from their envelopes and carefully unfolded and smoothed them a thousand times. But in fifty years he had never read a single word.

The fear of their impact had haunted him since the war. Now, with the century almost spent, he felt the time was right. He was an accomplished and successful man with an international reputation as a master language teacher, and the story of his life was such a potent mix of adventure and tragedy, dream and nightmare, that it had the power of myth. But until now not even the accumulated wisdom of a long and extraordinary life had enabled him to face the small packet of letters lying on the table.

At last, he felt he was ready. The letters were from his mother, aunt and uncle to a brother in New York, written at the time of their greatest peril. He picked up the solitary, typewritten envelope. It was from his uncle and Michel thought this might be the easiest to read for the man had been a businessman who wrote a businesslike letter. It had been written in Poland after he had been arrested and expelled from Breslau, a city then in Germany. He and his wife were among fifteen thousand German Jews who had been stripped of all their possessions and forced out of the country.

[1]

The letter had been hand-delivered to New York by a family friend who had crossed the Atlantic by liner.

Michel removed a single typed sheet of paper from the envelope. The sight of the familiar stationery bearing the letterhead WOLF GROSS - the family wholesale wine and liquor business - already stirred powerful memories.

[2]

He passed quickly over the banal opening paragraphs to reach the nub at the bottom of the first page: ‘Our emigration to the United States looks very bad. A letter from the American consul-general in Berlin states we will have to wait ten to fifteen years for a quota number. What shall we do? And what will happen? Our situation is well known to you. I ask you urgently to do everything possible. To address yourself energetically to the responsible immigration officials and to intervene on our behalf to send us a visa as quickly as possible. We wish you success and wait to hear from you. With all best wishes and heartfelt greetings - we hope for good news. Your brother-in-law.’

As Michel read these words something terrible and unexpected happened to him. For the first time in his life he was gripped by homicidal fury. The feelings aroused were primitive and brutal and thrust him into an extreme and alien psychological state. He had suffered internment and torture in the war, but had never experienced such corrosive hatred. Even his involvement in the arrest and interrogation of war criminals - whip-carrying SS officers and concentration camp executioners - had never triggered wrath like this. He had felt disgust and contempt for these men but now the emotions he experienced were utterly different. The act of a consul who sacrificed human lives on the altar of an American quota system ignited a rage of such violence he could have killed without pity or compunction.

[3]

Michel turned over the typewritten sheet and was slammed by another almost unbearable emotional blow as he caught sight of the handwriting of his beloved aunt. She had written a single, despairing paragraph: ‘Forgive me for writing so little but I’m completely down. I am so low I cannot write myself. Everything seems hopeless. What are we to do?’

The plea for help to a brother living in the haven of the United States - not yet at war - was an unadorned, final testament from the doomed.

[4]

All the papers needed for entry into America had long been in order, with sworn affidavits from family members guaranteeing financial support, but everything depended on obtaining an American quota number. The hopeless tone of his uncle’s letter conveyed the unwritten acknowledgement that nothing could be done -and the man who wrote it would not live to discover that the quota that could have saved him was never filled.

[5]