The Things They Cannot Say (12 page)

Read The Things They Cannot Say Online

Authors: Kevin Sites

After our Christmas meeting, my correspondence with Sperry over the next year is sporadic and shows his significant mood swings, likely from continued drug and alcohol use. I'm familiar with this, recognizing the chemically induced patterns of emotional highs and lows in myself. In some e-mails he seems helpless, in others defiant.

February 21, 2010 (e-mail from Sperry to me)

Sorry I have been really struggling with all my demons lately. I keep numbing myself up with weed, pills, and alcohol. I have been thinking about trying to tell the doctors at my next Marine Corps. doctor evaluation that I am totally fine and trying to release me. I was a great saw gunner and they need my talents over there. I hate being on the sidelines watching other boys and men fight this war. I can walk and pull my trigger finger. I think I am addicted to combat. Sorry for all the delay i have been numbing myself pretty good and trying to forget about how fucked up this world is. I want to be there for you as well I know you know the same pain. How do you cope with pain and mind-racing? I think I might check myself back in a VA hospital but if i do that there go my chances of the army. I hate being on the sidelines, I use to be important now everyone takes me for granted. I am so lost. . . . . .Peace

September 14, 2010 (Facebook message from Sperry to me)

Well lets get right back into it. I have time to contemplate everything in depth lately. The man that was James before everythingâwas motivated, naive, full of hope, and had innocence. I just feel like that man died over there and I am stuck with an existence that does not feelâit just calculates everything, the risk of going out in public, numb to any emotion I act emotions out so people think I am somewhat fine. But I haven't felt them then unless I am going 160 mph on a crotch rocket . . . I am told why are you not seeing your doctors? What are they going to do for me? They are not going to understand at all what I am going thru from the constant pains in my head, upper back, and hips, knees, feet. To not sleeping for days, nightmares, lack of feeling anything but anger, flashbacks, breaking down at the drop of a hat. To asking why did I lose twenty-six friends and I am still here. I constantly contemplate what the last few seconds for my friends were [like]. What were they feeling? I contemplate my death daily. Also my daughters. When I look at people I try not to, but I picture what they would look like dead. I smoke pot non-stop just to keep me from exploding. It calms me down. I think that if suicidal veterans would receive pot for PTSD it would calm them down and help them think things out. I have almost died so many times, I can't even count. . . . I don't know what to do anymore. Giving up is not an option. I am not a quitter.

L

ater, I learn through Facebook postings that Sperry has separated from his wife, Cathy. I'm not surprised. The challenges to their relationship seemed nearly insurmountable. Cathy told me that the effect of Sperry's drinking and multiple medications had left her feeling isolated and alone. There were also the occasions, she said, when he was verbally abusive and his explosive temper sometimes made her fear for the safety of her daughter and herself. I ask her about it. It takes her a few weeks to respond, but finally I receive this:

December 29, 2010 (Facebook message from Cathy to me)

Hi Kevin, I'm sorry, I didn't mean to blow you off. It's just that it's been easier to just push my feelings aside and not think about it. And to be honest it does make me a little nervous having so many personal details out there. As far as our marriage, I feel like we are done. It hurts me to see him in pain and I really hope that he gets help and finds happiness, mostly for Hannah's sake. I care about him and his well-being, but our marriage lacked passion for years. Maybe I am being selfish, but I feel like for years he put me down and I started to believe it and it turned me into a person I didn't like. Maybe it was because of his own insecurities that he knew he was weak inside and was afraid of me being strong. But for the first time in my life I feel strong and independent. I feel like him and I brought out the worst in each other, some of it Iraq is to blame, but also at 19, we didn't know how to be married and never truly respected each other. One example of this is, he got a motorcycle loan without talking to me first, and I got a credit card without telling him . . . we just started bad habits like that from the beginning. He is leaving this week to go to a rehab center out of state and I am very happy he is finally going to get help. I want to see him get better and I will always care about him, and I do feel sad for what has become of us. But, my feelings have changed for him, and it wouldn't be fair to either of us to stay together. We have so many different views on everything and are not the same people we married. And I don't feel like we are capable of being what each other wants in a mate. I do enjoy the freedom of being able to figure out who I am without someone standing in my way and I feel like I am a stronger person than I was then when we were together.

Shortly after, I see on Facebook that Cathy has changed back to her maiden name.

At the same time I e-mailed Cathy, I had also sent James a note asking him if he thinks his marriage was a casualty of his war injuries and PTSD and whether there are behaviors he wishes he could change.

He writes me back through Facebook, responding thoughtfully and candidly.

December 14, 2010 (Facebook message from Sperry to me)

I really do not like being away from Cathy because she was always that rock for me, but with all the stress that of the whole experience, I just was not the same confident person anymore I became very selfish, mood swings, and numb to any emotion. Unfortunately, I said and did so many bad things. There wasn't a name in the book that I didn't call her. I was just angry and violent. Then I found pot. This helped a ton into relaxing me and thinking through situations before I would fly off the handle. But the negatives that have come with it were the smell of it and me. Cathy saw that it helped me and wanted me to have it. During this time it was almost daily war between us. We both didn't care what we said to each other. We hurt each other a lot. But it got to a point that we would yell at each other so much that a brick wall just went up in our mind to what each other was trying to say. There were also very beautiful times and great times that we all had together. From group parties to beach days. Not all of it was yelling and fighting there were some great days in there. My anger was extreme I regret that more then anything I am deeply and truly sorry to Cathy for all that I put her threw emotionally. She is a very different person now she is very resourceful and strong willed. But at least in my presence I don't see the passion she used to have for me or her art or photography. I miss that more then anything she was a very bubbly person around me and I have not seen her truly happy in years. I am sure other people have but not me. She use to love me so much that nothing would have broken it but war did and the way I handled all the pain I have had to endure from weekly migraines and vomiting so much that my teeth are thinning out and decaying, to my hips, shoulders, chest and knee to all the emotional trauma that lost of so many friends. My whole world-view has changed to one of utter disgust of the human kind. Not the people trying to get by, but the hierarchy that rule and exploit the world. I am extremely afraid and depressed of what will be left of this earth for my daughter. I still live in the house you visited. Cathy is living a half hour away. I try and see Hannah three days a week. She is why I'm trying to get better. I am going to go to a in patient treatment center in Georgia called the Shepherd Center. I need to do this for myself. How have you been Kevin? Hannah asks about you everyone once in a while. She still sleeps every night with the panda you got her.

By January, I get a message from Sperry that he has checked himself into the Shepherd Center in Atlanta, Georgia, as he said he would. The Shepherd Center is a not-for-profit hospital that specializes in research, treatment and rehabilitation for people with spinal cord and brain injury. Sperry seems a perfect candidate and seems upbeat about the prospects for himself.

A

month later, he sends me another note about the center's holistic approach to treating post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury, which seems to mix the healing philosophies of both East and West.

February 2011 (Facebook message from Sperry to me)

The treatment has been great. They work on every aspect of your problems. They educate you on what happens to your brain after TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury) and PTSD. Then you have groups on PTSD, adjustment to civilian life, cognitive functions, controlling anger. They have a physical therapist that works on whatever ever hurts and explores why and how to treat or strengthen. They have a warrior life coach that shows you how to change your thought process. Then you have doctors that just work on pain management and general care. They aso do funcitonal life skills, yoga, tai chi, acupunctureâjust about everything.

I think about everything that James Sperry has been through and how he first wrote me during the middle of his own debilitating physical pain and mental chaos. Despite his embittered state, his feelings of being damaged, worthless and guilty for just being alive, he was still able to reach out to me with comfort for my own battlefield guilt. He's also shared with me the real-time narrative of his own healing. For all his wounds and the horrors he's experienced, I see the warrior still, a man whose humanity abides. Recognizing my small efforts on his behalf years ago, he returned the favor with an offer of redemption, helping protect me from what he knew to be the most unforgiving postwar enemy, ourselves. I smile when I see this self-portrait he posted on Facebook at the end of his treatment. The caption reads simply, “New and improved James.”

“New and improved James”âJames Sperry's profile picture on Facebook, May 12, 2011

Postscript

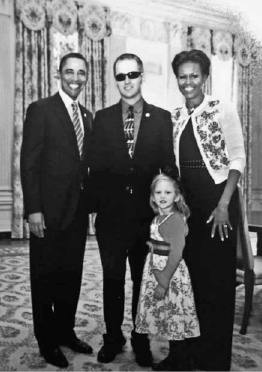

James is now a mentor with the Wounded Warrior Regiment and travels around the country helping other veterans to get treatment. After learning of his ordeal, President and Mrs. Obama invited James, Hannah and Cathy for a visit to the White House.

James Sperry and Hannah with the president and his wife

Gunnery Sergeant Leonard Shelton, U.S.M.C. (on left)

3rd Battalion, 5th Marines

The Gulf War (1991)

Chapter 4: Someone's Not Listening

After that battle everything was pretty foggy. I stopped praying, I grew up in a Christian environment. But I didn't believe it anymore. Human flesh melting on steel?

T

he evidence was mounting, but Marine Sergeant Leonard Shelton still didn't believe he would actually go to war. He didn't want to believe it. His unit was already deployed in the baking sands of the Saudi Arabian desert, the first potential combat deployment for the light armored infantry battalion that had just been activated six years earlier in 1985. Their LAV-25s were amphibious, eight-wheeled rapid-transit personnel carriers with a maximum speed of sixty miles per hour and were topped with a 25 mm cannon. They operated with a crew of three and could transport four to six Marines. Even though he was the commander of one of the LAV-25s, Shelton had never been in real combat before and was not prepared for what he was about to encounter.

“We were being kind of lazy in the back of the vehicles, trying to hide from the sun,” he says. “We weren't taking it seriously. Our behavior showed we weren't taking it seriously.”

Like all soldiers with time on their hands they would goof on each other mercilessly but then share stories about their homes and families. Shelton, a black kid from Cleveland, Ohio, says he joined the military as a way to escape a personal sense of confusion from events he suffered as a childâsexual abuse, he claimed, by a member of his own extended family. While the Marines weren't a completely natural fit for him, he found they provided him with purpose and direction. He also found camaraderie and friendship with young men from places he likely would've never been exposed to. One of them was a lance corporal named Thomas Jenkins from the historical gold-mining town of Mariposa, California. Jenkins's family was of pioneer stock. Jenkins himself was trained as an EMT and spent the summers fighting fires for the U.S. Forest Service.

Shelton says that when they were first training on the LAVs he and Jenkins would sometimes race their vehicles against each other when no one was watching. Their shenanigans continued in Saudi Arabia for a time. But then Alpha Company commander Captain Michael Schupp saw what was happening and gathered his men together.

“He put us in a

school circle

. He actually talked to us and didn't yell at us,” says Shelton. “He talked to us like human beings, like Marines. âI want to bring us all home and I need your help,' he told us. The look in his eyes of his concern and care, his sincerity, changed everything for me. We had to depend on each other.”

It wasn't long before Shelton and his unit got to see the real face of war. It would be the first actual ground engagement of the Gulf War, the culmination of a coalition air campaign that had begun twenty-two days earlier. Shelton's light armored infantry battalion, operating under the designation Task Force Shepherd, was dug in near the Kuwaiti border. They were miles ahead of the main fighting task force and their role was to be a trip wire of sorts, both an early warning and early challenge to any advancing Iraqi forces. On January 29, 1991, elements of three Iraqi divisions, two infantry and one tank, crossed the border into Saudi Arabia from Kuwait in a large attack designed to draw coalition forces into a ground battle. The movement triggered the American Marine recon teams and LAV units, which scattered along the border.

“This is the first time we were engaging in combat,” says Shelton. “There was lots of confusion, lots of firepower, lots of fog. The first engagement started at dusk when we were fired on by Iraqi tanks.”

The primary fighting took place along a perimeter the coalition forces called Observation Post 4. While Shelton's LAV could lay down harassing fire, its 25 mm chain gun had little chance of penetrating the hulls of the Iraqi T-55 and T-72 main battle tanks.

“It was crazy, man, when we got the air support in and we were shooting at tanks, trying to hit their view box, but we didn't get up and personal until they were all destroyed,” he says.

Shelton's unit was reinforced in the rear by platoons of LAV-ATs, similar to LAV-25s, but with mounted TOW antitank missiles as their primary weapons instead of 25 mm chain guns. These could actually take out the Iraqi tanks once they were in range. At one point during the fighting Shelton heard an explosion from behind. At first, he and others thought that the Iraqi forces may have penetrated their lines and were now firing behind them. What had actually happened was that one of the reinforcing LAV-ATs spotted what they thought was an Iraqi tank within the American lines and requested permission to fire their TOW missile. The missile cleared its tube and found its target with a tremendous explosion. But the TOW hadn't hit an Iraqi tank. It hit another American LAV-AT a few hundred meters ahead of them. The missile penetrated the rear hatch of the LAV designated “Green Two,” detonating its supply of more than a dozen missiles stored in the rear. Eyewitnesses say it erupted into a tremendous fireball, instantly killing all four crewmembers, including Green Two's commander, Corporal Ismael Cotto. Cotto, twenty-seven, was a smart Puerto Rican kid from the South Bronx who had defied the odds of his poor neighborhood by not only graduating from high school but also attending college for three years, before fulfilling his dream of enlisting in the Marines. Shelton knew him from their time being deployed together.

The mistakes and confusion of that early engagement only seemed to get worse. A few hours into the fight, coalition forces began receiving air support from American A-10 Thunderbolts.

*

But the planes had difficulty locating Iraqi tanks within the lines and began dropping flares over the battleground to provide illumination. One of the flares landed near an American LAV-25, Red Two. After-action reports indicate that the Red Two's vehicle commander attempted to identify himself as a “friendly,” but that didn't prevent one of the A-10s from firing an AGM-65 air-to-ground missile, which destroyed the LAV and killed all of its crew with the exception of the driver, who was ejected from the vehicle. An after-battle investigation by the Marines suggested that a malfunctioning missile, rather than human error, caused the incident. Regardless, the end result was that seven more Marines were dead at the hands of their own forces, including Shelton's friend Lance Corporal Thomas Jenkins.

*

Together, the incidents resulted in eleven of the first American deaths in the Gulf ground warâall of them from inaptly named “friendly fire.”

It wouldn't be until daybreak, after the initial fighting ended, that Shelton would learn of what happened to Jenkins and Cotto, that his friends had been killed not at the hands of the Iraqis but rather by their own troops. But American commanders didn't have time to deconstruct the mistakes that led to the killing of their own men. During that first battle, the Iraqis had captured and occupied the border town of al-Khafji. What the Iraqi troops didn't realize, however, was that a handful of recon Marines were still hiding inside some of the buildings when the town was captured. These Marines would stay in their hiding spots, undiscovered, and would later help coordinate a counterattack from within, by directing A-10s to strike against Iraqi tanks around al-Khafji.

Shelton's forces helped support the counterattack the next day, providing fire support for advancing Saudi and Qatari troops, who were part of the American-led coalition brought together to oust the Iraqis after their invasion and occupation of Kuwait. But when Shelton's 25 mm chain gun jammed, his platoon leader ordered Shelton's vehicle to pull back and assist the company gunnery sergeant Leroy Ford in the rear. Shelton says that's when he saw the images that he would never be able to clear from his mind.

“When I got off the vehicle I asked Gunny Ford, âWhat do you need?' He had his back against the gate of the Humvee. I looked to the left and the poncho had flown off the bodies with a gust of wind, and that's when I went into shock. Jenkins was lying there completely burnt. His body was completely charred. All I could see were the whites of his teeth. I knew it was him because the gunny had already labeled . . . he had a tag on his boots. I also noticed that it was their vehicle. Right then I got into a state of shock, I couldn't speak, I couldn't talk, this was a blow that was more real than I could ever imagine. I fell to my knees, I looked at him [Gunny Ford] to help me with my feelings. Nothing.”

Nearly twenty years later Shelton is still overcome with the imagery, just as vivid and real as if he were looking at it now. After he tells me the story, he begins weeping, inconsolably, into the phone. I begin to realize what a risk I've been taking in asking these soldiers and Marines to take me back to their most difficult moments, to relive their most painful memories of war. While I might be able to get them to take me there, I wonder, while listening to Shelton's grief, if sharing their war stories might have the unintended consequence of making things worse.

“It could've been the confusion, or the rage, but I kept shouting they were dead and âI don't want to do this shit anymore.' I was angry and confused. I thought [the platoon leader] had set me up to see the bodies,” says Shelton, sobbing.

“But when I was walking back to my vehicle, he's actually trying to calm me down, trying to get me to refocus. It was in a gentle way. Still, I didn't want them touching me, I didn't want them around me. Because they didn't see what I saw,” he says insistently. “They couldn't tell me that it was going to be all right, because there wasn't anything anyone could say. They couldn't tell me anything that would fix what I had experienced. I just wanted to be left the fuck alone. I was shocked. I was in shock, man. I remember getting back on the vehicle after I saw them on the desert floor. I looked at my gunner and the lieutenant was on radio; I hadn't responded for five to thirty minutes. He kept calling me on the radio and I couldn't speak. I'm looking at my gunner and he says to me, âCan you please say something to him please?' Finally, I say over the radio, âThey're dead, they're dead, they're all dead!' ”

Shelton pauses and after what seems like several minutes, he continues. “At first there was silence,” Shelton says, “then you hear back over the radio, âCalm down, Blue 2 [Shelton's radio call sign], calm down.' I could tell my gunner was afraid. But I didn't want it, I didn't want to hear what he had to say. We never even talked about it for the whole time. It hurt too damn much. I didn't feel a sense of fear of running away, just rage. The initial shock of death, it was more than rage. I never want to feel that way again. It was animalistic. I never want to feel that way again. You get angry and want to kill. The rage is just incredible. Then we got back into the fight. We were just firing at everything. God, man, I never knew who they were [the Iraqi soldiers]. I didn't know who they wereâwho the fuck are these people?

“After the fighting was done I was so exhausted. It was like something was gone in me. It was like part of something was gone. This was my world; there was nothing else. After that battle everything was pretty foggy. I stopped praying; I grew up in a Christian environment, but I didn't believe it anymore. Human flesh melting on steel? Someone's not listening. I did a lot of raids after that. I volunteered for everything. Anger drove a lot of that for me. I wanted to find something to do. I didn't care after that first battle. It was a relief for me. I didn't feel sad about it, bad about it, I was just really pissed off. The only way you're going to go home is to do this job.”

It took two days to drive the Iraqis out of al-Khafji and Shelton's light armored infantry battalion was ordered to cross the border into Kuwait. After the fierce initial fighting and the loss of the eleven Marines, it was a circumspect moment for the unit.

“It was two

A.M

., February 1991, before we crossed into Kuwait,” says Shelton. “We had already burned most of our letters [so they wouldn't fall into enemy hands]. But I kept some and a picture of my son, Tyrone. At dawn when it's supposed to get sunny and you look across the horizon and it's completely black, they [Iraqis] set the oil fields on fire.”

To shield their movements as well as to create chaos in the wake of their retreat, Iraqi forces set fire to as many as six hundred oil wells as they began pulling out of Kuwait and back to Iraq. The images of the plumes were so thick they could be seen from space. To Shelton, the orange flames dancing over a vast, flat desert with black smoke turning day into night created an apocalyptic landscape, both bleak and surreal. As his vehicle moved into Kuwait through a pathway cleared of mines, the engine malfunctioned and the vehicle came to a halt.

“I'm watching people go off into the horizon. I get up on top of the vehicle. I took off my flak jacket and my helmet. I wanted to get shot. There were incoming rounds and I just wanted to get hit.” But no one obliged him. He put his helmet and body armor back on as his LAV was towed behind the lines to be repaired.