The Third Reich at War (103 page)

‘Operation Bagration’ opened the way for further victories all along the line. In the north, Soviet troops advanced as far as the Baltic, west of Riga; sent to rescue the situation, Scḧrner managed to fight back and recapture enough of the coastline to restore the line of communication, but his forces still had to retreat from Estonia and much of Latvia to avoid getting cut off. On 5-9 October 1944, Soviet troops pushed through again to the sea. The German forces lacked the resources for a counter-attack, but supplies and reinforcements came in by sea. A new note of desperation characterized their fighting as they defended the German territory of East Prussia. Soviet lines of communication were now over-extended. The German forces managed to slow down the Soviet advance until it ground to a halt. However, the Red Army had also launched an attack on Finland in June 1944, completing the relief of Leningrad and convincing the Finns that there was no option but to sue for peace. On 4 September 1944 a new government under Marshal Mannerheim signed an armistice under which the 1940 borders were to be restored and any German troops in the country arrested and interned. Further south, Model’s Army Group North Ukraine, weakened by the transfer of troops and equipment to Army Group Centre, was attacked by a series of savage armoured blows that sent it reeling back to the Carpathian mountains. Red Army commanders were helped by a massive superiority in arms and equipment, and by supremacy in the air after Germany’s fighter force had been redeployed to deal with Allied bombing raids from the west. Soviet artillery was being produced in huge quantities to pulverize the enemy before the tanks moved in. Particularly feared was the Katyusha rocket launcher, first used at Smolensk in 1941. It had been kept absolutely secret, so that when it came into action for the first time, firing dozens of rockets against the enemy with a huge noise, not only German troops but also Red Army soldiers fled in panic. Initially rather inefficient, with a range of less than 10 miles, by 1944 the device had been improved and was being manufactured en masse. German soldiers called it the ‘Stalin Organ’ from the appearance of its closely packed launch-tubes. They had no equivalent to use in eturn.

240

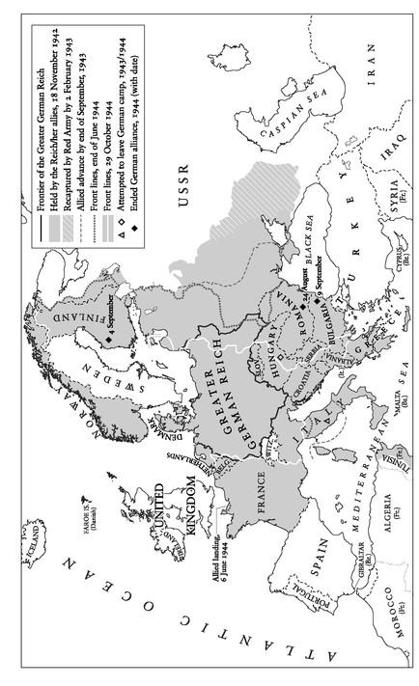

19. The Long Retreat, 1942-4

By the autumn of 1944 Soviet forces were fast approaching the gates of Warsaw. Stalin announced the appointment of a puppet Polish government, a rival to the exiled Polish regime in London. The exiled regime’s underground Home Army, a nationalist organization opposed to the communists, was being crushed by the Red Army as it moved into Polish territory. Nevertheless, when Stalin called upon the citizens of Warsaw to rise up against their German oppressors, in the expectation that Soviet forces would shortly be entering the city, the Home Army in the city decided to stage an uprising on 1 August 1944, fearing that, if it did not, Stalin would brand it pro-German, and hoping in any case to gain political influence by taking control of the traditional capital of Poland. The Home Army in Warsaw was poorly equipped, since most of its weapons and ammunition were being used for partisan activities in the countryside, and it was ill prepared. Its commanders had paid little attention to the ghetto uprising the previous year, and learned nothing from its fate. With ‘Molotov cocktails’, pistols and rifles, the Poles fought a stubborn defence against tanks, artillery, machine-guns and flame-throwers. For two months, the terrible scenes of 1943 were repeated on a larger scale, as German SS and police units commanded by Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski confined the insurgents to isolated areas, then reduced them to pockets of resistance, and finally wiped them out altogether, razing most of the city to the ground in the process. 26,000 German troops were killed, wounded or missing, but the Polish dead, men, women and children, numbered more than 200,000. Bach-Zelewski, employing Ukrainians, Soviet renegades and convicts drafted in from the concentration camps, massacred everyone he could find. An insurgent nurse described a typical scene as German and Ukrainian SS troops entered her hospital,

kicking and beating the wounded who were lying on the floor and calling them sons of bitches and Polish bandits. They kicked the heads of those lying on the ground with their boots, screaming horribly as they did it. Blood and brains were spattered in all directions . . . A contingent of German soldiers with an officer at its head came in. ‘What is going on here?’ the officer asked. After driving out the murderers, he gave orders to clear up the dead bodies, and calmly requested those who had survived and could walk to get up and go to the courtyard. We were certain they would be shot. After an hour or two another German-Ukrainian horde came in, carrying straw. One of them poured some petrol over it . . . There was a blast, and a terrible cry - the fire was right behind us. The Germans had torched the hospital and were shooting the wounded.

241

Similar and worse incidents repeated themselves throughout the Polish capital during these weeks. Himmler had ordered the whole city and its population to be destroyed. The centre of Polish culture would exist no longer. If the uprising was seen historically, he told Hitler, ‘it is a blessing that the Poles are doing it.’ It would enable Germany to bring the ‘Polish problem’ to a decisive end.

242

Stalin held back the Red Army while it focused on establishing bridge-heads on the Vistula and Narva rivers. He did nothing to assist the few Anglo-American planes that tried to airlift supplies to the insurgents. Most of the drops fell into German-held territory, and Stalin’s refusal to allow the planes to use Soviet airfields, along with the reluctance of the air force commanders, ensured that the airlift had no effect. From Stalin’s point of view, the uprising was a success: it inflicted heavy losses on the Germans, and it wiped out the politically inconvenient Polish Home Army as well. Once the last resisters surrendered, on 2 October 1944, he moved his forces in to take over the devastated city.

243

‘You have to seal your eyes and your heart,’ wrote the Warsaw-based German army officer Wilm Hosenfeld as the unequal fight continued. ‘The population is being pitilessly exterminated.’

244

After the Warsaw uprising was finally defeated, he watched the ‘endless columns of the captured rebels. We were totally amazed by the proud bearing they showed when they came out.’ The women in particular impressed him, marching past, heads held high, singing patriotic songs.

245

His attempt to get the captured resisters recognized as enemy combatants and so subject, at least in theory, to the laws of war, was predictably rebuffed by his superiors. Hosenfeld was ordered to interrogate the survivors. ‘I try to rescue everyone,’ he wrote, ‘who can be saved.’

246

Resistance was also mounting in the west, and particularly in France, where the Maquis now numbered scores of thousands of men and women, engaged in sabotaging German military installations in preparation for the invasion of France across the English Channel. Elaborate deception measures mounted by British and American intelligence services persuaded the German commanders that the invasion would come in Norway or near Calais or some other seaport. Over a million British, American, French, Canadian and other Allied troops were assembled in southern England under the general command of US general Dwight D. Eisenhower. On the night of 5-6 June 1944, more than 4,000 landing craft and over 1,000 warships convoyed the troops across the Channel while three airborne divisions began parachuting down behind the German defences. With the German navy effectively out of action, the German air force seriously weakened by losses in the preceding months and German forces dispersed over other areas and lacking the crack divisions concentrated on the Eastern Front, resistance was weaker than expected. Pulverized by naval and aerial bombardment, German defences were overwhelmed by the force of the landings, and except on Omaha Beach the resistance was quickly overcome. By the end of 6 June 1944, 155,000 men and 16,000 vehicles had been safely landed by the Allied operation. Prefabricated ‘Mulberry harbours’ were towed in and assembled, and more Allied forces landed and joined up from their five beachheads before the German army could rush in sufficient reinforcements to repel them. The capture of Cherbourg by 27 June 1944 provided them with a seaport, and huge quantities of men and equipment began to come over. German reinforcements were rushed to the front and began to put up stiff resistance, but the German commanders, Rundstedt and his subordinate Rommel, had no effective strategic plan for dealing with the invading forces, who now began to fight their way slowly across Normandy. This was now a war on two fronts.

247

Hitler reacted predictably by blaming this situation on the generals. They were constantly plying him with pessimistic assessments of the situation, he raged, and demanding withdrawals and retreats instead of staying put and fighting to the last. On 1 July 1944, worn out by the constant arguments with the Leader, Chief of the Army General Staff Kurt Zeitzler broke down, and simply abandoned his office. Hitler had him drummed out of the army in January 1945 and denied the right to wear a uniform. General Heinz Guderian was appointed his replacement on 21 July 1944. In the west, Field Marshal von Rundstedt was sacked two days later, along with Hugo Sperrle, the air force commander who had made a name for himself in the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, but was now blamed by his Leader for failing to mount an effective airborne defence against the Allied invasion. Field Marshal Günther von Kluge was appointed to replace Rundstedt. On the Eastern Front, Field Marshal Ernst Busch was sacked because of the catastrophic defeat of his Army Group Centre in Operation Bagration, and replaced by Field Marshal Walter Model, one of the few senior officers whom Hitler held in continuing high esteem. As he left the Berghof for the last time on 14 July 1944 to return to his field headquarters at the ‘Wolf’s Lair’ in Rastenburg, Hitler’s contempt for so many of his generals was becoming even more open than before.

248

III

The military catastrophes of the spring and early summer of 1944 led to an upsurge of resistance not only in occupied Europe but also in the German Reich itself. Already, the defeats of the previous year had spread disillusion with the regime. The devastating effects of the bombing weakened the authority of the regime still more. Nevertheless, open acts of resistance or defiance were still rare. Individual acts of defiance were met with arrest, trial and not infrequently execution. Collective resistance was difficult in the extreme. Social Democratic and Communist resistance organizations had been crushed by the Gestapo by the mid- 1930s and the leading figures in both parties were either in exile or in prison or concentration camp. Not only the more restrictive police regime of the war years but also the Nazi- Soviet Pact had a dampening effect on the will of former labour movement activists to organize any kind of oppositional activity before June 1941. And the euphoria created by the stunning military victories of 1939 and 1940 was shared by many in the working class, including former Social Democrats. As a precaution, too, the Gestapo arrested and incarcerated a number of former Communist functionaries on the invasion of the Soviet Union in case they should start a campaign of subversion. It was only in 1942, after the defeat of the German army before Moscow, that clandestine Communist resistance groups began to emerge again, in strongholds of the industrial working class like Saxony, Thuringia, Berlin and the Ruhr. Some of them were able to establish contact with the exiled party leadership in Moscow, but it was only intermittent, and in general there was little central co-ordination. The Communists managed to put out some leaflets urging opposition to the Nazis and even advocating acts of sabotage, but in general they achieved relatively little before they too were smashed by the Gestapo. The most spectacular action was undoubtedly that mounted by a group of young Jewish Communists and their sympathizers, led by Herbert Baum, who, as we have seen, managed to blow up part of an anti-Soviet exhibition staged by Goebbels in Berlin, though without causing any serious damage or any casualties. They too were quickly betrayed to the Gestapo; thirty were arrested and tried by the People’s Court; fifteen of them were executed.

249

Since the mid-1930s, the official party line from Moscow had emphasized the need for Communists to collaborate with Social Democrats in a ‘popular front’. But this tactic faced severe difficulties on both sides. The Social Democrats justifiably suspected the clandestine Communist groups of being under far more intensive surveillance than they were themselves, and the dangers of collaboration were dramatically illustrated on 22 June 1944 when a meeting in Berlin between the Social Democrats Julius Leber and Adolf Reichwein and a group of Communist functionaries resulted in the arrest of all those involved. As far as the Communists were concerned, it was more than likely that when the war was over the Social Democrats would re-emerge as their major rivals for the allegiance of the industrial working class, so that any co-operation could only be strictly tactical and temporary and should not involve concessions to a likely future political enemy. Within the concentration camps, and above all in Buchenwald, Communists formed their own groups, which could at times achieve a limited degree of prisoner self-management. The appointment of Communists as capos and block leaders was encouraged by the SS camp management, who saw the Communists as reliable and effective in this role. For their part, the Communist prisoners tried to maintain solidarity amongst themselves and protect their comrades, devolving difficult and dangerous work on to other categories of prisoner such as the ‘asocials’ and criminals. Through maintaining good relations with the SS they also hoped to improve conditions generally in the camp and so benefit all the inmates in the long run. In such a situation there were only limited prospects of meaningful co-operation with Social Democratic or other political prisoners. Solidarity within the Communist group was all-important. This precarious strategy, trying to strike a balance between ideological purity on the one hand, and self-protection through collaboration with the SS on the other, was to lead to widespread and sometimes bitter controversy after the war.

250