The Third Reich at War (16 page)

Already at the key meeting with Bouhler in late July 1933, Heyde, Brandt, Conti and others involved in the planning of the adult involuntary euthanasia scheme had begun to discuss the best method of carrying it out. In view of the fact that Hitler wanted around 70,000 patients to be killed, the methods used to murder the children seemed both too slow and too much likely to arouse public suspicion. Brandt consulted Hitler on the matter, and later claimed that when the Nazi Leader had asked him what was the most humane way of killing the patients, he had suggested gassing with carbon monoxide, a method already put to him by a number of physicians and made familiar through reports of suicides and domestic accidents in the press. Such cases had been investigated in depth by the police, and so Bouhler’s office commissioned Albert Widmann, born in 1912, and an SS officer who was the top professional chemist in the Criminal-Technical (or, as we would say, Forensic Science) Institute of the Reich Criminal Police Office, to work out how best to kill large numbers of what he was told were ‘beasts in human form’. He worked out that an airtight chamber was required, and had one built in the old city prison at Brandenburg, empty since the construction of a new penitentiary at Brandenburg-G̈rden in 1932. SS construction workers built a cell 3 metres by 5, and 3 metres high, lined with tiles and made to look like a shower-room so as to dull the apprehensions of those brought into it. A gas pipe was fitted along the wall with holes to let the carbon monoxide into the chamber. And as a last touch, an airtight door was installed, with a small glass window for viewing what was happening inside.

249

By the time it was finished, probably in December 1939, the gassings in Posen had already taken place, and had been personally observed by Himmler: undoubtedly the method had been suggested by Widmann or one of his associates to local SS officers in Posen, at least one of whom had a chemistry degree and was in touch with leading chemists in the Old Reich.

250

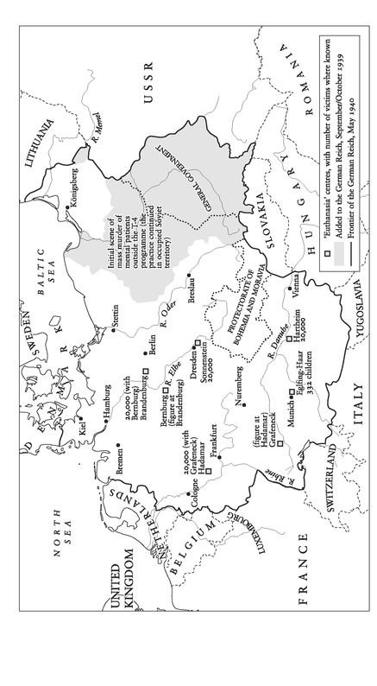

Himmler’s subordinate Christian Wirth, a senior official in the Stuttgart police, was one of those who attended the first demonstration of gassing in Brandenburg, along with Bouhler, Brandt, Conti, Brack and a number of other officials and physicians from T4 headquarters in Berlin. They took their turn to watch through the window as eight patients were killed in the gas chamber by carbon monoxide administered by Widmann, who told them how to measure the correct dose. All approved. Several other patients, given supposedly lethal injections by Brandt and Conti, had failed to die immediately - they were later gassed too - and so it was concluded that Widmann’s procedure was quicker and more effective. Soon the gas chamber in Brandenburg, which now went into regular service and continued to be used for killing patients until September 1940, was joined by other gas chambers built at the asylum in Grafeneck (Ẅrttemberg), which operated from January to December 1940, Hartheim, near Linz, which opened in May 1940, and Hadamar, in Hesse, which began operating in December 1940, replacing Grafeneck. These were former hospitals taken over by T-4 for exclusive use as killing centres; other gas chambers also came into use at hospitals that continued their previous functions, at Sonnenstein, in Saxony, which opened in June 1940, and Bernburg, on the river Saale, which opened in September the same year, replacing the original facility at Brandenburg.

251

Each centre was responsible for killing patients from a specific region. Local mental hospitals and institutions for the handicapped were required to send in their details to the T-4 office, together with registration forms for long-term patients, schizophrenics, epileptics, untreatable syphilitics, the senile and the criminally insane, and those suffering from encephalitis, Huntington’s disease and ‘every type of feeble-mindedness’ (a very broad and vague category indeed). At least to begin with, many physicians in these institutions were unaware of the purpose of this exercise, but before long it must have become clear enough. The forms were evaluated by politically reliable junior medical experts approved by their local Nazi Party offices - very few who were recommended to the T-4 office refused to play their allotted role - and then vetted by a team of senior officials. The key criterion was not medical but economic - was the patient capable of productive work or not? This question was to play a crucial role in future killing operations of other kinds, and it was also central to the evaluations carried out by T-4 physicians when they visited institutions that had failed to submit registration forms. Behind this economic evaluation, however, the ideological element in the programme was obvious: these were, in the view of the T-4 office, individuals who had to be eliminated from the German race for the sake of its long-term rejuvenation; and for this reason the killings also encompassed, for example, epileptics, deaf-mutes and the blind. Only decorated war veterans were exempted. In practice, however, all these criteria were to a high degree arbitrary, since the forms contained little real detail, and were processed at great speed and in huge numbers. Hermann Pfannm̈ller, for instance, evaluated over 2,000 patients between 12 November and 1 December 1940, or an average of 121 a day, while at the same time carrying out his duties as director of the state hospital at Eglfing-Haar. Another expert, Josef Schreck, completed 15,000 forms from April 1940 to the end of the year, sometimes processing up to 400 a week, also in addition to his other hospital duties. Neither man can have spent more than a few seconds to take the decision on life or death in each case.

252

The forms, each marked by three junior experts with a red plus sign for death, a blue minus sign for life, or (occasionally) a question mark for further consideration, were sent to one of three senior physicians for confirmation or amendment. Their decision was final. When the completed forms were returned to the T-4 office, the names of the patients selected for killing were sent to the T-4 transport office, which notified the institutions where they were held and sent an official to make the necessary arrangements. Often the lists were so arbitrarily drawn up that they included patients valued by institution directors as good workers, so not infrequently other patients were substituted for them on the spot in order to fill the required quota. Patients who were not German citizens or not of ‘Germanic or related blood’ also had to be reported. This meant in the first place Jewish patients, who were the subject of a special order issued on 15 April 1940: some thousand Jewish patients were taken away and gassed or, later on, taken to occupied Poland and killed there, over the following two and a half years, on the grounds that Aryan staff had been complaining about them and could not be expected to treat them. Directors of psychiatric hospitals, like Hermann Pfannmüller on 20 September 1940, proudly reported at the appropriate moment that their institution was now ‘Jew-free’ after the last Jewish inmate had been killed or taken away.

253

For all categories of patients selected for killing, the procedure was more or less the same. On the appointed day, large grey coaches, of the kind used by the postal service to provide public transport in rural areas, arrived to take the patients away. Although the T-4 doctors and functionaries repeatedly asserted that these patients were insane and incapable of either making decisions for themselves or of knowing what was going on, this was in no sense the case for the great majority of those selected for killing, even if they were supposedly ‘feeble-minded’. Some patients initially welcomed the diversion provided by the coaches’ arrival, believing the assurances of the staff that they were going on an outing. But many realized only too well that they were being taken to their death. Doctors and nurses were not always careful to deceive them, and rumours soon began to course through Germany’s asylums and care institutions. ‘I am again living in a state of fear,’ wrote a woman from an institution in Stettin to her family, ‘because the cars were here again . . . The cars were here again yesterday and eight days ago as well, they took many people away once more, where one would not have thought. We were all so upset that we all cried.’ As a nurse said ‘See you again!’ to a patient in Reichenau as she got on the bus, the patient turned and replied that ‘we wouldn’t be seeing each other again, she knew what lay before her with the Hitler Law’. ‘Here come the murderers!’ one patient in Emmendingen shouted as the bus arrived. Staff often injected anxious patients with heavy sedatives so that they were loaded on to the coaches in a semi-comatose state. But some patients began to refuse injections, fearing they contained poison. Others offered physical resistance when they were being loaded on to the coaches, and the brutal violence meted out to them when they did so only increased the anxieties of the others. Many wept uncontrollably as they were hauled on board.

254

Once they arrived at their destination, the patients were met by staff, led to a reception room and told to undress. They were given an identity check and a perfunctory physical examination aimed mainly at gaining hints for a plausible cause of death to enter in the records; those with valuable gold fillings in their teeth were marked with a cross on the back or shoulder. An identifying number was stamped or stuck on to their body, they were photographed (to demonstrate their supposed physical and mental inferiority) and then, still naked, they were taken into a gas chamber disguised to look like a shower room. Patients still anxious about their situation were injected with tranquillizers. When they were inside the chamber, the doors were locked and staff released the gas. The patients’ death was anything but peaceful or humane. Looking through the peephole, one observer at Hadamar later reported that he had seen

some 40 to 50 men, who were pressed tightly together in the next room, and now slowly died. Some lay on the ground, others had sunk into themselves, many had their mouths open as if they could not get any more air. The way they died was so full of suffering that one cannot speak of a humane killing, the more so since many of those killed may well have had moments of clarity about what was happening. I watched the procedure for about 2-3 minutes then left, because I could not bear to look any longer and I felt sick.

255

4.Killing Centre of ‘Action T-

4’

, 1939-45

The patients were normally killed in groups of fifteen to twenty, though on some occasions many more were crowded into the cramped chambers. After five minutes or so they lost consciousness; after twenty they were dead. The staff waited for an hour or two, then ventilated the chamber with fans. A physician entered to verify death, after which orderlies generally known as ‘stokers’ (

Brenner

) came in, disentangled the bodies and dragged them out to the ‘death room’. Here selected corpses were dissected, either by junior physicians who needed training in pathology, or by others who had orders to remove various organs and send them to research institutes for study. The stokers took the corpses marked with a cross and broke off the gold teeth, which were parcelled up and sent to the T-4 office in Berlin. Then the bodies were put on to metal pallets and taken to the crematorium room, where the stokers often worked through the night to reduce them to ashes.

256

The families and relatives of the victims were only informed of their transfer to a killing centre after it had taken place.

257

A further letter was sent by the receiving institution registering their safe arrival but warning relatives not to visit them until they had safely settled in. Of course, by the time the relatives received the letter, the patient was in fact already dead. Some time later, the families were notified that the patient had died of a heart attack, pneumonia, tuberculosis, or a similar ailment, from a list provided by the T-4 office and augmented by notes made during their examination on arrival. Aware that they were in some sense acting illegally, the physicians used false names when signing the death certificate, as well as, of course, appending a false date, to make it appear that death had occurred days or weeks after arrival, instead of merely an hour or so. Delaying the announcement of death also had the side-effect of enriching the institution, which continued to receive the benefits, pensions and family subventions paid to the victims between the time of their actual death and the time officially recorded on the certificate. Families were offered an urn containing, they were told, the ashes of their unfortunate relative; in fact, the stokers had simply shovelled them in from the ashes that had accumulated in the crematorium after a whole group of victims had been burned. As for the victims’ clothes, they were, the relatives were informed, sent to the National Socialist People’s Welfare organization, although in reality, if they were of any quality, they usually found their way into the wardrobes of the killing staff. The elaborate apparatus of deception included maps on which the staff stuck a coloured pin into the home town of each person killed, so that if too many pins appeared in any one place, the place of death could be ascribed to another institution; the killing centres, indeed, even exchanged lists of names of the dead to try to reduce suspicion. Maximum efforts were made to keep the entire process secret, with staff banned from fraternizing with the local population and sworn not to reveal what was going on to anybody apart from authorized officials. ‘Anyone who does not keep quiet,’ Christian Wirth told a group of new stokers at Hartheim, ‘will go to a concentration camp or be shot.’

258