The Third Reich at War (27 page)

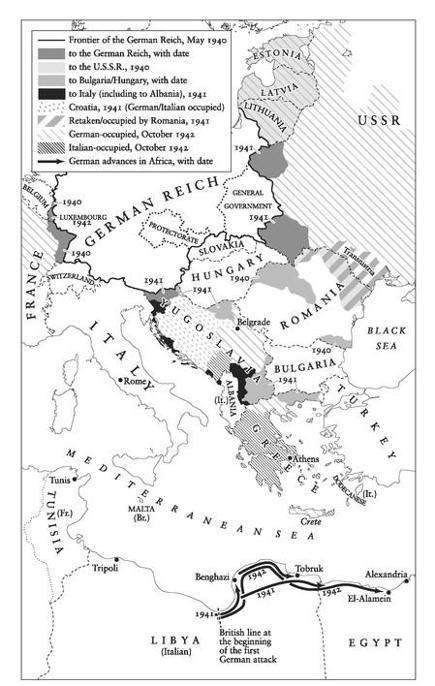

8. The War in the Mediterranean, 1940-42

The King and the government had already left for Crete, to where the remaining Greek, British and other Allied forces had retreated. But on 20 May 1941 German airborne forces landed on the island and quickly seized the main airfields, where further German troops now landed. The British commander on the island had not appreciated the importance of air defences. Without fighter planes he was unable to intercept the incoming airborne troops. By 26 May he had decided the situation was hopeless. A chaotic evacuation began. With complete command of the skies, German aircraft sank three British cruisers and six destroyers. They forced the Allies to abandon the evacuation on 30 May 1941, leaving some 5,000 men behind. Despite advance warning of these operations from German military signal traffic decoded at Bletchley Park, the British commander simply did not have enough strength on the ground or in the air. He was forbidden to redeploy his troops to the anticipated points of attack in case this should cause the German commanders to suspect their signals were being intercepted. More than 11,000 British troops were captured and nearly 3,000 soldiers and sailors killed. The whole operation was a disaster for the British. Churchill and his advisers were forced to concede that it had been a mistake to send troops to Greece in the first place.

110

Yet the German victories, spectacular as they were, came at a heavy price. The Greeks and their allies had fought determinedly, and the invading Germans had not escaped without casualties. In Crete, 3,352 out of a total of 17,500 invading German troops had been killed, persuading the German armed forces not to mount a similar airborne operation against Malta or Cyprus.

111

‘Our proud paratroop unit,’ wrote one soldier after the victory, ‘never recovered from the enormous losses sustained on Crete.’

112

More seriously, the occupation of the conquered territories soon proved to be far from a simple matter. While Bulgaria moved into eastern Macedonia and western Thrace, expelling over 100,000 Greeks from the area and bringing in Bulgarian settlers in a brutal act of ‘ethnic cleansing’, a puppet government was installed in Greece to maintain the fiction of independence. However, the real power lay with the German army, which occupied key strategic points on the mainland and some of the islands, especially Crete, and the Italians, who were given control over most of the rest of the country. As German troops entered Athens, tired, hungry and without supplies, they began to demand free meals in restaurants, to loot the houses in which they were billeted, and to stop passers-by in the streets and relieve them of their watches and jewellery. One inhabitant of the city, the musicologist Minos Dounias, asked:

Where is the traditional German sense of honour? I lived in Germany thirteen years and no one cheated me. Now suddenly . . . they have become thieves. They empty houses of whatever meets their eye. In Pistolakis’s house they took the pillow-slips and grabbed the Cretan heirlooms from the valuable collection they have. From the poor houses in the area they seized sheets and blankets. From other neighbourhoods they grab oil paintings and even the metal knobs from the doors.

113

While the ordinary troops were stealing what they could, supply officers were seizing large quantities of foodstuffs, cotton, leather and much else besides. All available stocks of olive oil and rice were requisitioned. 26,000 oranges, 4,500 lemons and 100,000 cigarettes were shipped off the island of Chios in the first three weeks of the occupation. Companies such as Krupps and I. G. Farben sent in agents to effect the compulsory purchase of mining and industrial facilities at low prices.

114

As a result of this massive assault on the country’s economy, unemployment in Greece rocketed and food prices, already high because of the damage caused by military action, went through the roof. Looting and requisitioning led to peasant farmers hoarding their produce and attacking agents sent from the towns to collect the harvest. Local military commanders tried to keep produce within their region, disrupting or even cutting off supplies to the major cities. Rationing was introduced, and while the Italians began to send in extra supplies to Greece to alleviate the situation, the authorities in Berlin refused to follow suit, arguing that this would jeopardize the food situation in Germany. Soon hunger and malnutrition were stalking the streets of Athens. Fuel supplies were unavailable, or too expensive, to heat people’s houses in the cold winter of 1941-2. People begged in the streets for food, ransacked rubbish bins for scraps, and in their desperation started to eat grass. German army officers amused themselves by tossing scraps from balconies to gangs of children and watching them fight for the pieces. People, especially children, succumbed to disease, and began dying in the streets. Overall death rates rose five- or even sevenfold in the winter of 1941-2; the Red Cross estimated that a quarter of a million Greeks died as a result of hunger and associated diseases between 1941 and 1943.

115

In the mountainous areas of northern Greece armed bands attacked German supply routes and there were some German casualties; the regional German army commander burned four villages and shot 488 Greek civilians in reprisal. In Crete, stranded British soldiers took part in resistance activities, in the course of which a German general was kidnapped. Whether or not the savage reprisals of the German army had any effect is uncertain. The general state of hunger and exhaustion of the Greek people meant that there were few attempts at armed resistance in the first year or so of the occupation, and no co-ordinated leadership.

116

III

The situation in occupied Yugoslavia was dramatically different. An artificial creation that had bound together in a single state a variety of ethnic and religious groups since the end of the First World War, Yugoslavia was torn by bitter inter-communal feuds and rivalries that broke out in full force as soon as the Germans invaded. The German Reich annexed the northern part of Slovenia, south of the Austrian border, while Italy incorporated the Adriatic coast down to (and including some of ) the Dalmatian islands and took over the administration of the bulk of Montenegro. Albania, an Italian possession since April 1939, occupied a large chunk of the south-east, including much of Kosovo and western Macedonia, as well as ingesting part of Montenegro, while the voracious Hungarians gobbled up the Backa and other areas they had ruled until 1918, and the Bulgarians, as well as seizing most of Macedonia from the Greeks, marched into the Yugoslav part of Macedonia. The rest of the country was split into two. Hitler was determined to reward his allies and to punish the Serbs. On 10 April 1941, the day that German forces entered Belgrade, the Croatian fascist leader Ante Paveli’, with German encouragement, declared an independent Croatia, encompassing all areas inhabited by Croats, including Bosnia and Hercegovina. The newly independent state of Croatia was far larger than rump Serbia. Paveli’ immediately allied himself with Germany and declared war on the Allies. Like his equivalent, Quisling, in Norway, Paveli’ was an extremist who had little popular support. A nationalist lawyer, he had formed his organization when King Alexander had imposed a Serb-dominated dictatorship in 1929 following demonstrations in which Serb police had killed a number of Croatian nationalists. Known as the ‘Ustashe’ (insurgents), Pavelić’s movement had scored its most spectacular coup in 1934 when its agents had collaborated with Macedonian terrorists in the assassination of the Yugoslav king, along with the French Foreign Minister, during a state visit to France in 1934. The subsequent repression of his organization had meant that Paveli’ had been obliged to run it from exile in Italy, where he had converted it into a fully fledged fascist movement, complete with a racial doctrine that saw the Croatians as ‘western’ rather than Slav. He gave it the mission of saving the Catholic, Christian West against the threat posed by Orthodox Slavs, atheistical Bolsheviks and Jews. By the beginning of the 1940s, however, he is estimated to have won the support of no more than 40,000 out of 6 million Croats in Yugoslavia.

117

Hitler initially wanted to appoint the leader of the moderate Croatian Peasant Party, Vladko Maˇek, as head of the new state, but when he refused, the choice fell on Paveli’, who returned from exile and proclaimed a one-party state of Croatians.

118

Paveli’ set about recruiting young men from the urban sub-proletariat for the Ustashe, and almost immediately set in motion a massive wave of ethnic cleansing, using terror and genocide to drive out the new state’s 2 million Serbs, 30,000 Gypsies and 45,000 Jews or turn them at least into nominal Croats by converting them to Catholicism. Ultra-nationalist students and many Croatian-nationalist Catholic clergy, especially Franciscan monks, joined in the action with gusto. Already on 17 April 1941 a decree proclaimed that anyone guilty of offending against the honour of the Croat nation, either in the past, present or future, had committed high treason and thus could be killed. Another decree defined the Croats as Aryan and banned intermarriage with non-Aryans. Sexual relations between male Jews and female Croats were outlawed, though not the other way round. All non-Croats were excluded from citizenship. While the new treason law was at least paid lip-service in the towns, the Ustashe did not bother even with the appearance of legality in the countryside. After shooting dead some 300 Serbs, including women and children, in the town of Glina in July 1941, the Ustashe offered an amnesty to the inhabitants of the surrounding villages if they converted to Catholicism. 250 people turned up at the Orthodox Church in Glina for the ceremony. Once inside, they were greeted not by a Catholic priest but by Ustashe militia, who forced them to lie down and then beat their heads in with spiked clubs. All over the new Croatia, similarly terrible scenes of mass murder were enacted during the summer and autumn of 1941. On several occasions, Serb villagers were herded into the local church, the windows boarded over, and the building burned to the ground along with everybody in it. Croatian Ustashe units gouged out the eyes of Serbian men and cut off the women’s breasts with penknives.

119

The first concentration camp in Croatia opened at the end of April 1941, and on 26 June a law was enacted providing for a network of camps across the country. The purpose of the camps was not to hold opponents of the regime, but to exterminate ethnic and religious minorities. In the Jasenovac camp system alone, more than 20,000 Jews are thought to have perished. Death was due above all to disease and malnutrition, but Ustashe militia, egged on by some Franciscan friars, frequently beat inmates to death with hammers in night-long sessions of mass murder. At the Loborgrad camp, 1,500 Jewish women were subjected to repeated rape by the commander and his staff. When typhus broke out in the camp at Stara Gradiska, the chief administrator sent sufferers to the disease-free camp at Djakovo so the inmates there could be infected too. On 24 July 1941, the curate of Udbina wrote: ‘Up to now, my brothers, we have been working for our religion with the cross and the breviary, but the time has come when we shall work with a revolver and a rifle.’

120

The head of the Catholic Church in Croatia, Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac, a bitter opponent of Orthodox ‘schismatics’, declared that the hand of God was at work in the removal of the Serbian Orthodox yoke. Paveli’ was even granted a private audience with the Pope on 18 May 1941. Eventually, however, Stepinac was moved to protest against forced conversions that were all too obviously achieved through terror, though his condemnation of the killings did not come until 1942, when Father Filipovi’, who had led murder squads at Jasenovac, was expelled from the Franciscan order. By 1943 Stepinac was condemning the registration and deportation to extermination camps of the remaining Croatian Jews. But this was all rather late in the day. By this time, probably about 30,000 Jews had been killed, along with most of the country’s Gypsies (many of whom died working in inhuman conditions on the Sava dike construction project), while the best estimates put the number of Serb victims at around 300,000. Such was the horror generated above all in Italy by these massacres, as reports of the atrocities were publicized by the thousands of Serbian and Jewish refugees who crossed the border into Dalmatia, that the Italian army began to move on to Croatian territory, declaring that it would protect any minorities it found there. But it was too late for most. In the longer term, the Croatian genocide created memories of deep and lasting bitterness among the Serbs. It still had not been forgotten by the time Serbia and Croatia eventually regained their independence after the collapse of the postwar Yugoslav state, in the 1990s.

121