The Third Reich at War (56 page)

The Third Reich also began to exploit the economies in subtler, less obvious ways. The exchange rate with the French and Belgian franc, the Dutch guilder and other currencies in occupied Western Europe was set at a level extremely favourable to the German Reichsmark. It has been estimated, for example, that the purchasing power of the Reichsmark in France was more than 60 per cent above what it would have been had the exchange rate been allowed to find its own level on the markets instead of being artificially fixed by decree.

33

Germany imported huge quantities of goods legitimately from the conquered countries as well as simply looting them, but it did not pay for them by increasing its own exports commensurately. Instead, French, Dutch and Belgian firms exporting goods to Germany were paid by their own central banks in francs or guilders, and the sums paid marked up as debts to the Reichsbank in Berlin. The debts, of course, were never paid, so that by the end of 1944, the Reichsbank owed 8.5 billion Reichsmarks to the French, nearly 6 billion to the Dutch, and 5 billion to the Belgians and Luxembourgers.

34

Altogether French payments to Germany amounted to nearly half of all French public expenditure in 1940, 1941 and 1942, and as much as 60 per cent in 1943.

35

Germany, it has been estimated, was using 40 per cent of French resources by this time.

36

Altogether, well over 30 per cent of the wartime net production of the occupied countries in the west was extracted by the Germans.

37

The effects of these exactions on the domestic economies of the occupied countries were significant. German control over central banks in the occupied countries led to the end of restrictions on the issuing of banknotes, so that ‘occupation costs’ were paid not least by simply printing money, leading to serious inflation, made worse by the shortages of goods to purchase because they were being taken to Germany.

38

German companies were able to use the overvalued Reichsmark to gain control of rival firms in France, Belgium and other parts of Western Europe. They could be helped by German government regulation of trade and raw materials distribution, which generally worked to their advantage. Yet the enormous deficit Germany ran up through the non-repayment of debts to the central banks of the occupied countries obviously made it more difficult to export the capital needed to buy up companies in the conquered countries. I. G. Farben, the German Dye Trust, did manage to seize control of much of the French chemical industry, and German firms, above all the state-sponsored Hermann G̈ring Reich Works, snapped up much of the mining and iron and steel industries in Alsace-Lorraine. German state sponsorship of the Hermann G̈ring Reich Works gave it an obvious advantage over private enterprise in the acquisition of foreign firms. Many of the enterprises taken over were state-controlled or foreign-owned; the Aryanization of Jewish firms also played a role here, though in overall terms they did not amount to very much. Many of the biggest private enterprises, however, escaped takeovers, including major Dutch multinationals like Philips, Shell and Unilever, or the huge steel combine that went under the name of Arbed. Of course, the German occupiers supervised the activities of these firms in many ways, but in most cases they were unable to exert direct control or reap direct financial benefits.

39

This was not least because in the occupied countries in Western Europe, national governments remained in existence, however limited their powers might be, and property laws and rights continued to apply as before. From the point of view of Berlin, therefore, economic cooperation, however unequal the terms on which it was based, was what was required, not total subjugation or expropriation along the lines followed in Poland. The occupation authorities, civil and military, set the overall conditions, and opened up opportunities for German firms, for instance through Aryanization (though not in France, where Jewish property was controlled by the French authorities). All that German companies looking to expand their influence and reap the profits of the occupation could do, therefore, was to ingratiate themselves with the occupying authorities in the attempt to steal a march on their rivals.

40

The policy of co-operation dictated from Berlin limited the freedom of action of such companies. It was born not simply of expediency - the desire to win the co-operation of France and other Western European countries in the continuing struggle against Britain - but also of a grander vision: the concept of a ‘New Order’ in Europe, a large-scale, pan-European economy that would mobilize the Continent as a single block to pit against the giant economies of the USA and the British Empire. On 24 May 1940 representatives of the Foreign Office, the Four-Year Plan, the Reichsbank, the Economics Ministry and other interested parties held a meeting to discuss how this New Order was going to be established. It was clear that it had to be presented not as a vehicle of German expansionism but as a proposal for European co-operation. Germany’s policy of trying to wage war with its own resources was clearly not working. The resources of other countries had to be harnessed as well. As Hitler himself told Todt on 20 June 1940: ‘The course of the war shows that we have gone too far in our efforts to achieve autarky.’

41

The New Order was intended to reconstitute autarky, self-sufficiency, on a Europe-wide basis.

42

What was required, therefore, as Hermann G̈ring, head of the Four-Year Plan, put it on 17 August 1940, was ‘a mutual integration and linkage of interests between the German economy and those of Holland, Belgium, Norway and Denmark’, as well as intensified economic cooperation with France. Companies such as I. G. Farben leaped in with their own suggestions as to how their own particular industrial needs could be met, as a memo from the company put it on 3 August 1940, by the creation of ‘a large economic sphere organized in terms of self-sufficiency and planned in relation to all the other economic spheres of the world’.

43

Here too, as a representative of the Reich Economics Ministry explained on 3 October 1940, circumspection was necessary;

One can take the view that we can simply dictate what is to happen in the economic field in Europe, i.e. that we simply regard matters from a one-sided standpoint of German interests. This is the criterion which is sometimes adopted by private business circles when they are dealing with the questions of the future structure of the European economy from the point of view of their own particular sphere of operations. However, such a view would be wrong because in the final analysis we are not alone in Europe and we cannot run an economy with subjugated nations. It is quite obvious that we must avoid falling into either of two extremes: on the one hand, that we should swallow up everything and take everything away from the others, and, on the other, that we say: we are not like that, we don’t want anything.

44

Steering such a middle course was roughly the line taken by the visionary economic imperialists who had developed thinking about a German sphere of economic interest - sometimes known as

Mitteleuropa

, ‘Central Europe’ - before the First World War. It would, economic planners thought, involve the creation of Europe-wide cartels, investments and acquisitions. It might require government intervention to abolish customs barriers and regulate currencies. But from the point of view of German industry, the New Order had to be created above all by private enterprise. European economic integration under the banner of the New Order was to be based not on state regulations and government controls, but on the restructuring of the European market economy.

45

Pursuing such a goal meant avoiding as far as possible giving the impression that the conquest of Western European countries amounted to nothing more than their economic subjugation and exploitation. At the same time, however, German economic planners were clear that the New Order would be set up above all to serve German economic interests. This involved a sleight of hand that could sometimes be quite sophisticated. Mindful, for example, of the bad name that had clung to the concept of reparations since 1919, the Third Reich did not demand financial compensation from the defeated countries; how could it anyway, since the reparations Germany had had to pay from 1919 to 1932 had been to compensate for the damage done to France and Belgium by the German invasion of these two countries in 1914, and nobody had invaded Germany in 1940. So instead the victorious Germans imposed what were called ‘occupation costs’ on the defeated nations. These were ostensibly meant to pay for the upkeep of German troops, military and naval bases, airfields and defensive emplacements in the conquered territories. In fact, the sums extracted under this heading exceeded the costs of occupation many times over, amounting in the case of France to some 20 million Reichsmarks a day, enough, according to one French calculation, to support an army of 18 million men. By the end of 1943, nearly 25 billion Reichsmarks had found their way into the German coffers under this heading. So enormous were these sums that the Germans encouraged the French to contribute to their payment by transferring shares, and, before long, majority control over vital French-owned enterprises in the Romanian oil industry and Yugoslavia’s huge copper mines had passed to Party-dominated enterprises in Germany such as the ubiquitous Hermann G̈ring Reich Works and the newly established ‘multinational’, Continental Oil.

46

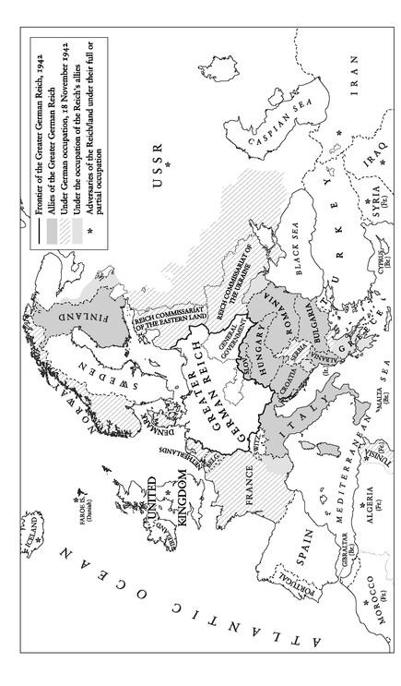

12. The New Order in Europe, 1942

I V

What this all reflected was the fact that from the point at which serious preparations began to be made for the invasion of the Soviet Union, ideas of economic co-operation began to take second place to the imperatives of economic exploitation. Some, like Speer, took these ideas relatively seriously.

47

But as far as Hitler was concerned, they were little more than a smokescreen. On 16 July 1941, for example, he devoted some attention to a declaration in a Vichy French newspaper that the war against the Soviet Union was a European war and therefore should benefit all European states. ‘What we told the world about the motives for our measures,’ he said, ‘ought . . . to be conditioned by tactical reasons.’

48

Saying that the invasion was a European enterprise was such a tactic. The reality was that it would be in Germany’s interests. This had long been clear to the Nazi leaders. As Goebbels declared on 5 April 1940: ‘We are carrying out the same revolution in Europe as we carried out on a smaller scale in Germany. If anyone asks,’ he went on, ‘how do you conceive the new Europe, we have to reply that we don’t know. Of course we have some ideas about it, but if we were to put them into words, it would immediately create more enemies for us.’

49

On 26 October 1940 he made it brutally obvious what these ideas boiled down to: ‘When this war is over, we want to be masters of Europe.’

50

By 1941, therefore, the conquered countries of Western Europe were being exploited by the Germans for all they were worth. Most of them had advanced industrial sectors that were intended to contribute to the German war effort. Yet it soon became clear that the French contribution was falling far short of what German economic and military leaders hoped for. Attempts to get French factories to produce 3,000 aircraft for the German war effort repeatedly stalled before an agreement was signed on 12 February 1941. Even after this, production was slowed down by shortages of aluminium and difficulties in obtaining coal to provide power. Only 78 planes were delivered by factories in France and the Netherlands by the end of the year, while at the same time the British had purchased over 5,000 from the USA. The following year, things improved somewhat, with 753 planes delivered to the German air force; but this was only a tenth of the quantity the British got from the Americans. Low morale, poor health and nutrition among workers, and probably considerable ideological reluctance as well, ensured that labour productivity in French aircraft factories was only a quarter of what it was in Germany. Altogether the occupied western territories managed to produce only just over 2,600 airplanes for German military use during the whole of the war.

51

Even with the addition of the substantial natural resources of the conquered areas of Western Europe, the economy of the Third Reich remained woefully short of fuel during the war. Particularly serious was the lack of petroleum oil. Attempts to find a substitute were unsuccessful. Synthetic fuel production only rose to 6.5 million tons in 1943, from 4 million in four years before. The Western European economies occupied in 1940 were massive consumers of imported oil, producing not a drop themselves, and so they merely added to Germany’s fuel problems as they were abruptly cut off from their former sources of supply. Romania supplied 1.5 million tons of oil a year, and Hungary almost as much, but this was by no means enough. French and other fuel reserves were seized by the occupying forces, reducing the supply of petroleum in France to only 8 per cent of pre-war levels. Germany’s Italian ally consumed further quantities of German and Romanian oil, since it too was cut off from other sources. German oil reserves never exceeded 2 million tons during the entire war. By contrast, the British Empire and the USA provided Britain with over 10 million tons of oil imports in 1942, and twice as much in 1944. The Germans failed to seize other sources of oil in the Caucasus and the Middle East.

52