The Third Reich at War (77 page)

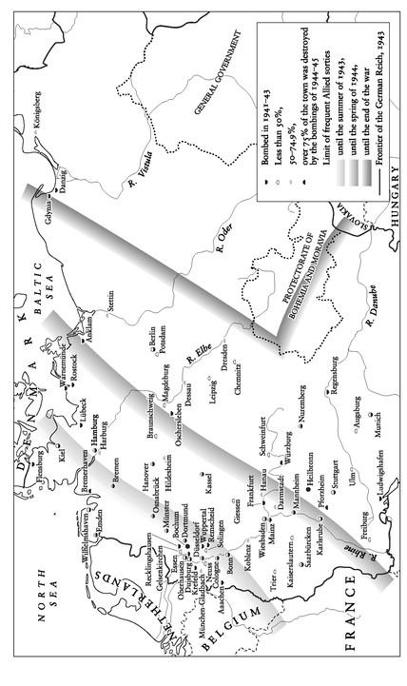

16. Allied Bombing Raids on German Cities, 1941-5

Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry poured out bile against the Allied bombing crews and their political masters. The Americans were gangsters, their air crews uncultivated mobsters taken out of the prisons. By contrast, the German media claimed, the British fliers were drawn mainly from the effete ranks of the aristocracy. Both, however, in the view propagated by the Nazi media, were in the service of Jewish conspirators, who were also manipulating Roosevelt and Churchill in their quest for the total destruction of Germany.

78

The propaganda did have an effect.

79

There were widespread reports from 1943 at the latest of people demanding reprisal attacks on London; but this was not so much in anger, rather in the belief that only this could prevent further raids on Germany and even defeat in the war in general.

80

‘Again and again,’ reported the Security Service of the SS, ‘one could hear: “If we don’t do something soon, nothing will help us any more,” or “We can’t watch much longer as everything we have is smashed to bits.” ’

81

In 1944 there was some popular anger against the pilots and crew of Allied bombers, under the psychological pressure of constant alarms, raids, death and destruction, and encouraged by Goebbels’s mass media. It began to express itself in violence against Allied airmen who were forced to bale out after their plane had been hit. On 26 August 1944 seven American airmen who had baled out over R̈sselsheim were beaten to death by an angry crowd, while on 24 March 1945 a British airman who landed by parachute in a field near Bochum was attacked by a soldier with his rifle-butt. He fell over and was surrounded by a crowd who kicked him, hurting him badly. Someone tried to shoot the airman but the gun jammed, so he was dragged away until a member of the crowd produced a hammer and beat him to death. Three other British airmen who had also landed in the area were arrested by the Gestapo, tortured and then shot. One local works fireman who protested to his workmates against these murders was denounced, arrested and shot by the Gestapo. Not only did the police fail to intervene to stop such incidents, but anyone who did was likely to be arrested and tried for ‘forbidden contact with prisoners of war’. The Party Regional Leader for Southern Westphalia ordered on 25 February 1945 that pilots ‘who have been shot down are not to be protected from the people’s anger’. Altogether at least 350 Allied airmen were lynched in the last two years of the war and a further sixty or so injured without being killed. In a particularly notorious incident, when fifty-eight British airmen had escaped on 24 March 1944 from a prisoner-of-war camp near Sagan in Lower Saxony, all those who were recaptured were shot by the Gestapo on the explicit orders of Heinrich Himmler. Yet these incidents have to be kept in perspective. The total number of Allied airmen who were lynched or shot by the Gestapo made up no more than 1 per cent of the total captured.

82

The hatred that animated such actions was a product above all of the last phase of the bombing, and was, as the Security Service of the SS noted, not really present before 1944. The Security Service’s observers noted calls among the population, especially those who had been bombed out of their homes, for the British to be gassed or ‘annihilated’, but added that ‘hate-filled-sounding words against England are often more an expression of desperation and the belief that the annihilation of England is the only rescue . . .

One cannot speak of hatred for the English people as a whole.

’ And they quoted one woman who had lost her home in a raid as saying: ‘It hurts me that all my things have gone for good. But that’s war. Against the English, no, I don’t have anything against them.’

83

THE LONG RETREAT

I

The sharp decline of morale amongst the German population in 1943 was not just the result of the intensification of Allied bombing raids on German cities, it also reflected a series of dramatic reverses in other areas of the war as well. Amongst these, one of the most disheartening was in North Africa. In the summer of 1942 Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had succeeded in capturing the key North African seaport of Tobruk and driving the British back into Egypt. But difficulties in supplying his troops by either land or sea weakened Rommel’s position, and the British stood their ground at El Alamein, where they prepared deep defensive positions and massed their forces ready for a counter-attack. On 23 October 1942, under yet another new general, the meticulous Bernard Montgomery, the British attacked the German forces with over twice the number of infantry and tanks that Rommel could assemble. Over twelve days they inflicted a decisive defeat on them. Rommel lost 30,000 men captured in his headlong retreat across the desert. Little over two weeks later the Allies, their command of the Mediterranean virtually unchallenged, landed 63,000 men, equipped with 430 tanks, in Morocco and Algeria. The German bid to gain control of North Africa and penetrate from there to the oilfields of the Middle East had failed. Rommel returned to Germany on sick leave in March 1943.

84

Defeat in North Africa turned into humiliation in mid-May, when 250,000 Axis troops, half of them German, surrendered to the Allies.

85

Its complete failure to disturb British control over Egypt and the Middle East denied the Third Reich access to key sources of oil. These failures once more signalled not only the fact that the British were determined not to give in, but also the massive strength of the far-flung British Empire, backed to an increasing degree by the material resources of the United States.

86

Reflecting privately on these failures in 1944, Field Marshal Rommel still believed that, if he had been provided with ‘more motorized formations and a secure supply line’, he could have seized the Suez Canal, thus disrupting British supplies, and gone on to secure the oilfields of the Middle East, Persia and even Baku on the Caspian Sea. But it was not to be. Bitterly, he concluded that ‘the war in North Africa was decided by the weight of Anglo-American material. In fact, since the entry of America into the war, there has been very little prospect of our achieving ultimate victory.’

87

It was a view that many ordinary Germans shared. Rommel was a brilliant general, the student Lore Walb confided to her diary. But, she went on: ‘What can he do with limited forces and little ammunition?’ After the recapture of Tobruk by the Allies in November 1942, she was beginning to wonder if this was ‘the beginning of the end’, and a few days later she began to fear that the entire war was being lost: ‘Will Heaven then permit us to be annihilated???’

88

The Third Reich was now beginning to lose its allies. In March 1943, King Boris III of Bulgaria decided that the Germans were not going to win the war. Meeting with Hitler in June, he thought it politic to agree to the German dictator’s request for Bulgarian troops to replace German forces in north-east Serbia so that they could be redeployed to the Eastern Front. But he refused to render any further assistance, and behind the scenes he began to put out peace feelers to the Allies, rightly fearing that the Soviets would disregard Bulgaria’s official stance of neutrality in the wider conflict. Hitler continued to put pressure on him, meeting with him again in August 1943. But before anything could come of their talks, events took an unexpected turn. Shortly after arriving back in Sofia, Boris fell ill, dying on 28 August 1942, aged only forty-nine. In the feverish climate of the times, rumours immediately spread that he had been poisoned. An autopsy carried out in the early 1990s revealed, however, that he had died of an infarction of the left ventricle of the heart. He was succeeded by Simeon II, who was only a boy, and the regency largely continued Boris’s policy of disengaging from the German side, spurred on by increasing numbers of Allied bombing raids on Sofia, starting in November 1943. Popular opposition to the war spread rapidly, and armed partisan bands formed under the leadership of the Soviet-inspired Fatherland Front, causing increasing disruption; British agents arrived to assist them, but the partisan movement failed to make much headway, and some of the British agents were betrayed and shot. Nevertheless, under these pressures, the government began to backtrack, repealing anti-Jewish legislation, and declaring full neutrality the following year.

89

Far more alarming to many Germans were the dramatic events that unfolded in Italy after their defeat in North Africa. On 10 July 1943 Anglo-American forces, ferried across by sea and backed by airborne assaults on defensive positions behind the beaches, landed in Sicily, which was occupied by a combination of Italian and German troops. Despite extensive preparations, the attack was far from perfectly executed. The landing forces mistook the planes flying overhead for enemy aircraft and started firing on them, weakening the airborne thrust. The British commander Montgomery split his forces in the east into a coastal and an inland column, as a result of which they only made slow progress against heavy German resistance. Syracuse was captured, but because of the delays in the British advance, the Germans managed to evacuate most of their troops across to the mainland. Still, the island eventually fell to the Allied forces. Ominously for the Italian Fascist dictator Mussolini, too, the citizens of Palermo had waved white flags at the invading Americans, and there were growing indications that ordinary Italians no longer wanted to continue fighting. Hitler visited Mussolini in northern Italy on 18 July 1943 to try to bolster his confidence, but his two-hour monologue depressed the Italian dictator and made him feel he lacked the will to carry on. The dictator’s prestige and popularity had never recovered from the catastrophic defeats of 1941, most notably in Greece. His relationship with Hitler had changed fundamentally after this: even Mussolini himself referred to Fascist Italy as no more than the ‘rear light’ of the Axis, and he soon acquired a new nickname: the Regional Leader of Italy. Hitler, always late to bed, had taken to sending him messages in the middle of the night, obliging him to be woken up to receive them; and the Italian dictator began to complain that he was becoming fed up with being summoned to meetings with him like a waiter by a bell.

90

While Italian troops continued to fight, they were losing their faith in the cause for which they were being asked to lay down their lives. Mussolini himself began to complain privately that the Italians were letting him down. Distrusting the ability of the Italians to carry on fighting, Hitler had already made plans to take over Italy and the territories it occupied in southern France, Yugoslavia, Greece and Albania. He put Rommel in charge of the operation.

91

As Allied planes began to bomb Italian cities, the prospect of an invasion of the Italian mainland by the Allies became imminent. German forces moved into the peninsula, indicating by their mere presence whose cause the Italians were now fighting for. Serious opposition to Mussolini’s dictatorship surfaced for the first time in many years and came to a head towards the end of July. In February 1943 Mussolini had carried out a purge of leading figures in his increasingly discontented Fascist Party. It had been growing ever more critical of his political and military leadership. This was virtually his last decisive act. Disoriented and demoralized, he began suffering from stomach pains that sapped his energy. He spent much of his time dallying with his mistress Clara Petacci, translating classic Italian fiction into German, or devoting himself to minor administrative issues. Since he was not only Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces but also held several major ministries, this meant that a vacuum began to appear at the centre of power. The sacked party bosses began to intrigue against him. Those in the Fascist Grand Council who either wanted more radical measures taken to mobilize the population or sought to place the further conduct of the war entirely in the hands of the military decided to strip him of most of his powers at a meeting held on 24- 5 July 1943 (the first since 1939). Few details were made known of this dramatic, ten-hour marathon. The leading moderate Fascist, Dino Grandi, who proposed the motion, later confessed that he had been carrying a live grenade throughout, in case of emergencies. But it was not necessary. Mussolini’s reaction to the criticisms levelled at him was feeble and confused. He hardly seemed to know what was going on and failed to put a counter-proposal, leading many to think he had no objections to Grandi’s motion. In the early hours of the morning, it was voted through by nineteen votes to seven.

92