The Third Reich at War (88 page)

According to Director Kloos in Stadtroda, the mother of a young idiot boy was told the following in the clinic at Jena: ‘Your boy is an idiot, without any prospect of developing, and he must therefore be transferred to the regional hospital in Stadtroda, where three physicians from Berlin examine the children at certain intervals and decide whether they should be killed.’

233

This laxness had to be stopped, he said. ‘As you know,’ he added in a second letter, ‘the Leader wants all discussion of the question of euthanasia to be avoided.’

234

Voices were also raised in protest from within the Confessing Church, most notably in October 1943, when a synod in Breslau stated publicly: ‘The annihilation of human beings simply because they are relatives of a criminal, old, or mentally ill, or belong to a foreign race, is not wielding the sword of state given to the authorities by God.’

235

Protestant welfare institutions like Bodelschwingh’s Bethel Hospital sometimes tried to delay the transport of patients to the killing centres, or to send them out of harm’s way, but even Bodelschwingh met with only limited success in these efforts.

236

The Catholic Church was initially hesitant, though it soon realized that the killing programme was continuing. A joint pastoral letter on the topic, drafted in November 1941 by a group of bishops, was suppressed by Cardinal Bertram, who was reluctant to exacerbate the situation still further in the wake of Galen’s sermon. Instead, early in 1943, the bishops instructed Catholic institutions not to co-operate with the registration of patients for the Reich Ministry of the Interior, which had ordered it at the end of the previous year with the obvious intention of compiling lists of people to be killed.

237

On 29 June 1943 Pope Pius XII issued an Encyclical,

Mystici Corporis

, condemning the way in which, in Germany, ‘physically deformed people, mentally disturbed people and hereditarily ill people have at times been robbed of their lives . . . The blood of those who are all the dearer to our Saviour because they deserve the greater pity,’ he concluded, ‘cries out from the earth up to Heaven.’

238

Following this, on 26 September 1943, an open condemnation of the killing of ‘the innocent and defenceless mentally handicapped and mentally ill, the incurably infirm and fatally wounded, innocent hostages and disarmed prisoners of war and criminal offenders, people of a foreign race or descent’ by the Catholic bishops of Germany was read out from the pulpit in churches across the land. The breadth of the terms in which it was couched was remarkable. Its overall effects were minimal.

239

V

Among the many people whom the Nazis regarded as racially inferior, a special position was reserved for the Gypsies. Himmler regarded them as particularly subversive because of their itinerant lifestyle, their alleged criminality and their aversion to regular, conventional employment. Racial mixing with Germans posed a eugenic threat. By September 1939 German Gypsies had been rounded up and registered with a special office in Berlin. Many of them were in special camps. As soon as the war broke out, the SS took the opportunity to put into effect what Himmler had already called the ‘final solution of the Gypsy question’.

240

Restrictions were placed on their movements, and many were expelled from border areas in the belief that their wanderings and their supposed lack of patriotism made them suitable for recruitment by foreign intelligence agencies. A plan to resettle them in occupied Poland was shelved while Himmler sorted out the resettlement of ethnic Germans there, but a meeting of SS officials chaired by Heydrich on 30 January 1940 decided that it was time for the plan’s implementation. In May 1940 some 2,500 German Gypsies were rounded up and deported to the General Government. In August 1940, however, it was decided to postpone further deportations until the Jews had been dealt with. While the SS dithered, the persecution of those Gypsies who remained in the Reich intensified. Gypsy soldiers were cashiered from the army, Gypsy children were expelled from schools, Gypsy men were drafted into forced labour schemes. Early in 1942 Gypsies in Alsace-Lorraine were arrested, and some of them were taken to concentration camps in Germany as ‘asocials’. 2,000 Gypsies in East Prussia were loaded on to cattle cars at the same time, and taken to Bialystok, where they were put in a prison, from which they were later moved to a camp in Brest-Litovsk. Meanwhile, Dr Robert Ritter’s research team, based in the Reich Health Office, was painstakingly continuing its registration and racial assessment of every Gypsy and half-Gypsy in Germany. By March 1942 the team had assessed 13,000; a year later the total assessed in Germany and Austria had reached more than 21,000; and by March 1944 the project was finally completed, with a final tally of precisely 23,822. However, by this time, many of those who had been assessed by Ritter and his team were no longer alive.

241

The killings began in 1942. The previous year, the Reich Criminal Police Office, which had already concentrated Gypsies from the Austrian Burgenland into a number of camps in the province, had persuaded Himmler to allow the deportation of 5,000 of them to a specially cordoned-off section of the Lo’dz’ ghetto. Plans to use the adult Gypsies for labour duties came to nothing, however. As typhus began to rage in the ghetto, particularly affecting the overcrowded and insanitary quarter where the Gypsies lived, the German administration decided to take them all to Chelmno, where the great majority - more than half of them children - were killed in mobile gas vans. Around the same time, SS Task Forces in occupied Eastern Europe were shooting large numbers of Gypsies as ‘asocials’ and ‘saboteurs’. In March 1942, for instance, Task Force D reported with evident satisfaction that there were no more Gypsies left in the Crimea. The killings commonly included women and children as well as men. They were normally rounded up together with the local Jewish population, stripped of their clothes, lined up alongside ditches and shot in the back of the neck. The numbers ran into thousands and included sedentary as well as itinerant families, despite the fact that Himmler made a clear distinction between the two. In Serbia, as we have seen, the regional army commander Franz Böhme included Gypsies in his arrests and shootings of ‘hostages’. One eyewitness of a mass shooting of Jews and Gypsies by men of the 704th Infantry Division of the regular German army on 30 October 1941 reported: ‘The shooting of the Jews is simpler than that of the Gypsies. One has to admit that the Jews go to their death composed - they stand very calmly, whereas the Gypsies cry, scream and move constantly while they already stand at the place of the shooting. Several even jump into the ditch and pretend to be dead.’ Harald Turner, the head of the SS in the area, alleged (without any evidence) that Gypsy men were working for the Jews in partisan warfare and were responsible for many atrocities. Several thousand were killed, although when the gassing of the remaining Serbian Jews in the Sajmiste camp began in February 1942, the Gypsy women and children held there were released.

242

The killing of Gypsies was also carried out by Germany’s Balkan allies. In Croatia, as we have seen, the Ustashe massacred large numbers of Gypsies as well as Serbs and Jews. Similarly, the antisemitic regime of Ion Antonescu in Romania ordered some 25,000 out of a total of 209,000 Romanian Gypsies to be deported to Transnistria, along with 2,000 members of a religious sect, the Inochentists, who refused on grounds of conscience to do military service. Those who were rounded up were mainly itinerant Gypsies, whom Antonescu made largely responsible for crime and public disorder in Romania. In practice, the arrests were often quite arbitrary in character, and the Romanian army protested successfully against the inclusion of some First World War veterans in the deportations. The deportees were described in 1942 as living in conditions of ‘indescribable misery’, without food, emaciated and covered in lice. Increasing numbers died of hunger, cold and disease. Their bodies were found on local highways; thousands had perished by the spring of 1943, when they were transferred to better housing in a number of villages and given jobs on public works projects. Only half of the deportees survived long enough to return to Romania from Transnistria with the retreating Romanian army in 1944.

243

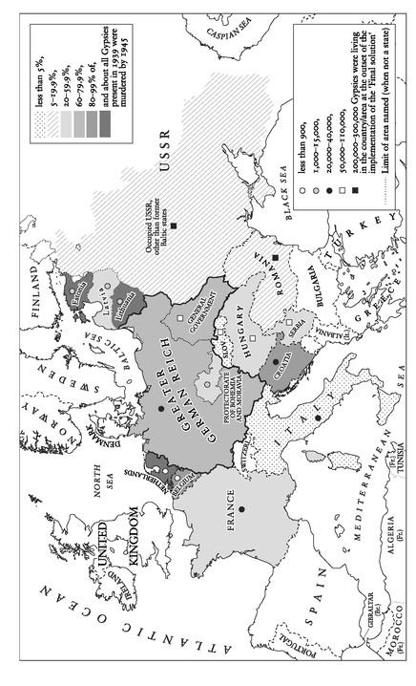

18. The Extermination of the Gypsies

Although these killings were on a large scale, they were far less systematic than those carried out by the Germans. On 16 December 1942 Himmler ordered the deportation of more than 13,000 German Gypsies to a special section of the Auschwitz camp.

244

The camp commandant Rudolf Höss recalled that the arrest of Gypsies was chaotic, with many decorated war veterans and even Nazi Party members being rounded up simply because they had some Gypsy ancestry. In their case there was no classification as a half- or quarter-Gypsy; anyone with even a small amount of Gypsy ancestry was regarded as a threat. The 13,000 constituted under half the Gypsy and part-Gypsy population of the Reich; many of the others were exempted because they worked in armaments and munitions factories, so that a considerable proportion of those deported were children. Thousands more were deported to Auschwitz from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. At Auschwitz-Birkenau they filled a special family camp. It eventually contained nearly 14,000 Gypsies from Germany and Austria, 4,500 from Bohemia and Moravia, and 1,300 from Poland. Hygiene was poor, conditions filthy, malnutrition rife, and inmates, especially children, rapidly succumbed to typhus and tuberculosis. The sick were selected on a number of occasions and sent to the gas chambers. Some 1,700 who came in from Bialystok on 23 March 1943 were killed shortly after arrival. Early in 1944 the majority of the Gypsy family camp’s men and women were taken to other camps in Germany for use as forced labourers. On 16 May 1944 the SS surrounded the family camp with the intention of sending the remaining 6,000 inmates to the gas chambers. Forewarned by the camp’s German commandant, the Gypsies armed themselves with knives, spades, crowbars and stones, and refused to leave. Fearful of causing a pitched battle, the SS withdrew. Over the following weeks, more Gypsies were taken in small batches for work in Germany. On 2 August 1944 Rudolf Ḧss, now reinstated as the main camp commandant, ordered the SS to round up the remaining 3,000 or so Gypsies, who were given food rations and told they too were being deported to another camp. His real intention, however, was to free up the Gypsy camp accommodation for large numbers of new incoming prisoners. The Gypsies were taken to the crematoria and put to death. Another 800, mostly children, were sent from Buchenwald in early October 1944 and killed as well. This brought the total number of Gypsies who died at Auschwitz to more than 20,000, of whom 5,600 had been gassed and the rest had died from disease or maltreatment. In his memoirs, unbelievably, Ḧss described them as ‘my best-loved prisoners’, trusting, good-natured and irresponsible, like children.

245

Gypsies in Nazi Germany were arrested, sent to concentration camps and killed not because, like Jews, they were thought to be so potent a threat to the German war effort that they all had to be exterminated, but because they were considered to be ‘asocial’, criminal, and useless to the ‘national community’. In Nazi Germany, of course, these supposed characteristics were thought to be largely inherited, and thus racial in origin. But this does not make the mass murder of German and European Gypsies a genocide in the same way as the mass murder of German and European Jews was. In most concentration camps, Gypsies were classified as asocial and made to wear the black triangle that denoted them as such. Sometimes, as we shall see in the next chapter, they were specially selected for medical experimentation; in Buchenwald there is no doubt that they were singled out for especially harsh treatment. At least 5,000 and possibly up to 15,000 remained in Germany during the war, and in January 1943 the police ordered that they were to be sterilized if they agreed to the operation. They were offered the inducement of permission to marry non-Gypsy Germans if they consented.

However, those who refused were liable to be put under heavy pressure to give their consent. A number were threatened with being sent to a concentration camp. Others successfully appealed on the grounds that the admixture of Gypsy blood in their veins was insignificant. Altogether, between 2,000 and 2,500 Gypsies were sterilized during the war, most of them classified by Ritter and his team as ‘asocial mixed-race Gypsies’. They fell into a similar category to that of so-called mixed-race Jews, a group that caused perpetual uncertainty amongst the Nazis as to what should be done with them. Overall, the Gypsies were not, in other words, the subject of a concerted, obsessive and centrally directed campaign of physical extermination that sought to eliminate them all, without exception. But the fact that the majority of them were also classified as ‘asocial’ imposed on them a double burden of discrimination and persecution. That is why so many of them were killed, while the vast majority of so-called mixed-race Jews were not. In the long run, of course, race laws and sterilization programmes were intended to eliminate both categories from the chain of heredity in what some have called a ‘delayed genocide’.

246