The Third World War - The Untold Story (26 page)

Read The Third World War - The Untold Story Online

Authors: Sir John Hackett

Tags: #Alternative History

Given the excellent liaison already established at Shannon between the French naval airmen and the Irish airport authorities, the arrival there on 4 August, within hours of the outbreak of war in Europe, of four ANG caused little stir. Nor did the landing, shortly afterwards, of a US Navy

Orion.

This aircraft had been following up a submarine contact some 100 miles south of Cape Farewell, which had been obtained by a Canadian frigate using a towed array passive sonar. Unfortunately the scent had gone cold, and the aircraft was ordered into Shannon, to operate under the Commander, Maritime Air, Eastern Atlantic.

On the morning of 5 August the

Orion

and two ANG were allotted tasks that took them far out into the Atlantic. Amidst the excitement of that day’s news this did not attract much attention. But what did cause a loud buzz of rumour and speculation in the Shannon communications centre and control tower was when, at 1722 hours, a distinctly French voice came over the loudspeakers monitoring the international distress frequency: ‘MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY’ it called, ‘THIS IS SIERRA QUEBEC BRAVO CHARLIE WE ARE BEING ATTACKED BY FIGHTERS LATITUDE 52.12 NORTH LONGITUDE . . .’

Here, as in many places all over Europe, the outbreak of war was signified not by any dramatic public announcement like Chamberlain’s address to the British people forty-six years earlier, but by a series of swift and violent encounters.

In this instance, the response was immediate and well orchestrated for the Mayday signal could mean only one thing: a

Kiev

-class carrier was out to the west and it must be found and sunk before it did any more damage. The two remaining ANG at Shannon and two

Nimrods

from an RAF base in Cornwall were launched on a search within half an hour. As the ANG climbed out on their search tracks the crews could see smoke rising from the refinery and the main hangars at Shannon and guessed correctly that a salvo of air-launched missiles, probably from a

Backfire,

had found their mark.

The search area was very large because of the missing and all-important longitude figure, but a fast westbound merchant ship broke wireless silence to report sighting a

Forger

aircraft on the horizon and this clue shrank the area of probability dramatically. With a new datum to work from, dawn was breaking when a

Nimrod

picked up the

Kiev

and its escorts on its radar.

At JACWA headquarters the operations staff were looking disconsolately at their meagre forces for attacking the enemy group. The specialized anti-shipping

Buccaneers

that had survived a raid on Murmansk the day before were being held at Bodo, Norway, to guard against Soviet naval incursions along that coast and they could muster only two or three aircraft from the UK. These would need in-flight fuelling and a fighter escort against the carrier. It could hardly be called a balanced force. But help came unexpectedly in the shape of fourteen

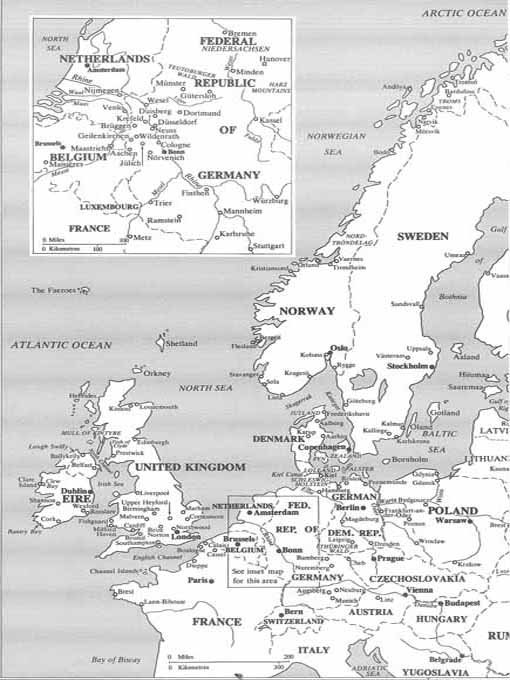

Marineflieger

(Federal German Naval Air Force)

Tornados

which arrived at Kinloss air base in Scotland as the planners were puzzling over the problem. This force, thanks to the decisiveness of its commander, Captain Manfred Steinhof, had got away from Nordholz in Schleswig-Holstein under the very noses of the advancing Soviets.

By 0900 hours, and after the French Ministry of Defence had got Irish agreement for the

Marineflieger

aircraft to refuel at Shannon despite the previous day’s damage, eight of the

Tornados

landed and refuelled. They were in the air again in half an hour to join their fighter escort of RAF

Tornados

backed up by a VC-10 tanker. A United States Navy

Orion

had by then taken over the shadowing of the

Kiev

force on its radar and it homed the

Tornados

in for the attack. The carrier was holed with her steering disabled and one of her escorts badly damaged as the force withdrew and the submarine

Splendid

arrived on the scene to despatch the stricken ships. Three

Tornados

were lost, one to a

Forger

and the others to missiles from the escorts. Manfred Steinhof’s aircraft ran out of fuel short of the Irish coast but he and his navigator were picked up by a fishing boat. The Third World War had broken out thirty-seven hours earlier, and this was just one action in the great tide of war that was engulfing Europe.

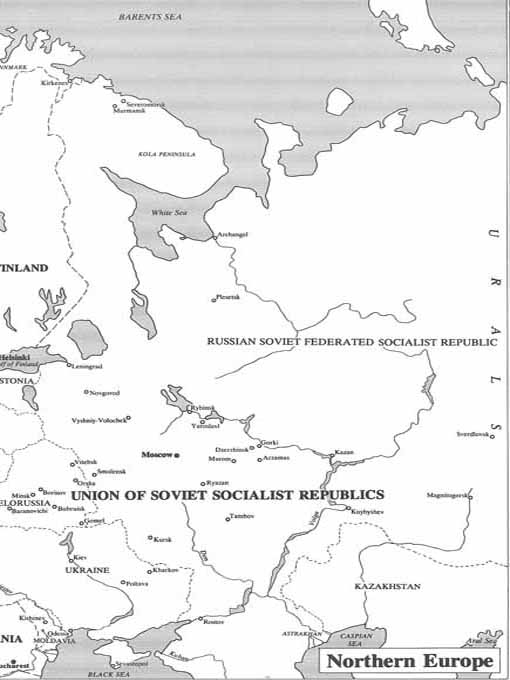

The contingency plan formulated by the Defence Council of the Politburo for the defence of the Soviet Union and its socialist allies against the aggressive designs of Western capitalism had two supreme aims: to cause the collapse of the Atlantic Alliance and to bring about the neutralization of neo-Nazi Germany. The second would lead to the first. The dismantling of the Federal Republic must, therefore, receive primary and very close attention.

To the Chief of the Soviet General Staff, Marshal P. K. Ogurtsov, an old cavalry soldier brought up in his profession in the 1930s to the use, incredible though it sounds today, of the sword as a weapon from the back of a horse (as, incidentally, was the main author of this book), the analogy was simple. Federal Germany was the point of the sword presented at the enemy; the outstretched right arm (‘at cavalry, engage - point!’) was Allied Command Europe; the hilt, which would come up against the victim’s body with extreme violence once the point was through, was NATO; the rider on the horse’s back, swinging forward with the thrusting, outstretched sword, planning, placing and timing the thrust, was the United States; the galloping horse giving the chief strength and impetus to the hilt, which, directed by the rider’s swinging body and extended arm, would hammer the pierced enemy out of his saddle, was Western capitalism. Reflecting by the stove in his dacha, the vodka bottle handy, the Marshal always admired the aptness of his analogy, only regretting that no one understood it any more. What had once been cavalry, riding horses and wielding

l’arme blanche,

had been suffocating in stinking tanks for nearly half a century.

The destruction of Federal Germany would mean the collapse of the Atlantic Alliance, the total demoralization of Europe, the withdrawal of the USA across the sea and swiftly widening opportunities for the spread of socialism throughout the world. The importance of the FRG was such, however, that an attack upon it would be no less than a total attack on NATO and would be resisted as such. It would have to be planned accordingly.

The initial assault had to be massive. To carry out the intentions of the Defence Council, ten fronts would be activated, two in the GDR, one each in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and the far north, all in the front line, with follow-up fronts in the Leningrad Military District, in Poland and in the Ukraine, while in Belorussia and the Ukraine there would be also two groups of tank armies comprising three tank armies each, making six tank armies to exploit success in the centre, or to be used otherwise as circumstances dictated. The initial assault at dawn on 4 August, following action in space to restrict surveillance, undercover operations to frustrate command and support, deep air bombardment in Europe to interdict forward movement of war material and reserves, and action at sea to begin the interruption of maritime reinforcement, would open with the utmost violence along the whole Warsaw Pact-NATO interface, from Norway to Turkey.

Since the Central Region of Allied Command Europe (ACE), against which three fronts threatened, with a fourth standing by in Poland, was to be the focal point of this immense operation, it is upon the Central Front that we now concentrate. In our earlier book,

The Third World War: August 1985,

published in the spring of 1987, we described at length and in some detail the course of the main operation in this theatre and other accounts have appeared in other places. We do not intend here to recapitulate all that has been written. It is upon more personal aspects of these events that we shall focus instead, sometimes at very close range.

No plans for a major land offensive in modern war can ever be followed for very long after the offensive opens. The plans are made as part of a long-term concept. They embrace the object of the operations as a whole; the dispositions and movements of the enemy as they are known at the time; the probable reactions of the enemy’s commanders; and, perhaps most important of all, the estimate of what will be necessary for logistic support. Preparations for this demand forethought and imagination. They must be made far in advance and have to cover a period much longer than that during which the original operational plan of attack can continue to be followed. The operational plan may at any time have to be radically altered in a matter of days, or even hours, as commanders respond to the requirements of a developing situation. Logistic support, involving the movement and positioning of huge tonnages of material of all kinds, from bridging equipment to missile and gun ammunition, from fuel and food to medical supplies, cannot be as easily adjusted as the fighting formations can be moved around the battlefields.