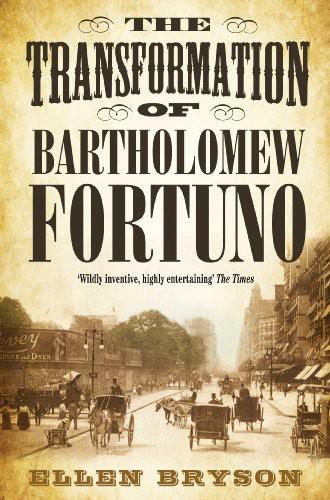

The Transformation of Bartholomew Fortuno: A Novel

Read The Transformation of Bartholomew Fortuno: A Novel Online

Authors: Ellen Bryson

Tags: #Literary, #Fiction

The

Transformation

of

Bartholomew

Fortuno

Transformation

of

Bartholomew

Fortuno

a novel

Ellen Bryson

H

ENRY

H

OLT AND

C

OMPANY N

N

EW

Y

ORK

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

Henry Holt

®

and are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright © 2010 by Ellen Bryson

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bryson, Ellen, 1949–

The transformation of Bartholomew Fortuno : a novel / Ellen Bryson.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8050-9192-2

1. Barnum’s American Museum—Fiction. 2. Curiosities and wonders—Fiction. 3. Freak shows—Fiction. 4. Circus performers—Fiction. 5. Barnum, P. T. (Phineas Taylor), 1810–1891—Fiction. 6. New York (N.Y.)—History—1775–1865—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3602.R984T73 2010

813'.6—dc22 | 2009045214 |

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums.

For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2010

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Illustrations by Cecilia Sorochin

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this

novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously

To

Sue Loesberg

An empty belly hears nothing.

—English proverb

The

Transformation

of

Bartholomew

Fortuno

L

IGHT FROM

A

PRIL’S FULL MOON SWEPT OVER

the Museum’s façade and down the building’s marble veneer. It illuminated the man-sized letters that hung high and large enough for a person as far uptown as Canal Street to see, spelling out B

ARNUM

’

S

A

MERICAN

Museum. From where I sat in my fourth-floor window, nearly all of Manhattan’s sky was visible.

I pressed my back against the window frame and watched the moonlight dissolve a fistful of clouds. Its glow rolled across Broadway to cover the spires of St. Paul’s and the front of City Hall, the mourning flag for Lincoln still listlessly hanging there, then spilled across the stables and roofs of houses abandoned to haberdashers and tailors. Most of higher society had stampeded uptown toward Fifth Avenue years ago, sticking to the highest part of the island and avoiding the land that sloped down toward the rivers on either side.

A bum staggered to a halt below me on a Broadway emptied by the encroaching night. He bellowed something indistinguishable, then tipped back on his heels to gawk, open-mouthed, up, up, up along the high Museum walls. He gazed in awe at the oval paintings of exotic tigers, whales, and a white-horned rhinoceros that were strung between each story of windows like pendants across the bosom of a well-endowed harlot. Who could blame the poor man for staring? Thousands before him had fallen for the gussied up old place, everyone from the city’s poorest paupers to the families of its Upper Ten—and once even a prince. They, too, had all been enticed by the Museum’s glitter. And

why not? The place was irresistible. Banners and fluttering flags beckoned from the roof like welcoming hands, and a pied-piper band spewed out terrible music from the balcony twelve hours a day, every day except Sunday. “I take great pains to hire the poorest musicians I can find,” Barnum liked to say. “They play so badly that the crowd moves into the Museum just to get out of earshot.” Colossal gas lamps flanked the front doors, and just inside stood a huge golden statue of Apollo, his horses rearing, a lyre dangling from his naked shoulder. The great illuminator’s index finger pointed toward the ticket window, just in case a visitor failed to see its shiny plaque.

The truth was, even I still found the place impressive after living here for nearly a decade. I’d been one of Phineas Taylor Barnum’s Human Curiosities (viewed thrice daily under the moniker Bartholomew Fortuno, the World’s Thinnest Man) since 1855, and, all in all, I could not complain about the way my life had unfolded. Few talents managed to make their way as far in the business as I had—Barnum’s Museum was the pinnacle of our trade—and I made a good living off the gifts nature had given me. I had found a comfortable home.

So it was with a great sense of satisfaction that I sat on my windowsill that chilly spring night, just after the end of the War of the Rebellion, unaware that change twisted its way to me through the darkened New York streets. Mindlessly, I ran a hand lovingly across my right shoulder, never tiring of the intricacies of socket and bone, then lit a cheroot in defense against the fetid air; the local breweries, tanneries, slaughterhouses, and fat-melting establishments smoldered away even in the middle of the night. Looking north I could make out Five Points, the Bowery, and the mean area around Greenwich Street that was jammed with immigrants and other unsavory folks. So many Irishmen, Italians, and Germans had crammed themselves below Houston Street that I could all but hear the clang of their knife fights. I avoided visiting that part of town. In fact, whenever possible, I avoided leaving Barnum’s Museum at all. A man like me had no business in the wider world. Let the outside world come to me and pay to do it.

Catching a whiff of spring blossoms from the West Side orchards, I couldn’t help but turn to Matina, who sat on my divan, tatting a lace doily to replace the one she’d stained with lamb gravy the week before. Next to her rested a tray of empty dishes from her evening snack and a pillow she’d embroidered for me years ago with the words

He Who Stands with the Devil Does Himself Harm.

“I told you it was possible to smell the orchards from here, my dear. Come and sniff for yourself.”

“All I smell is garbage,” Matina answered, from her seat. “Come away from the window, Barthy. I’ve something I want to show you before I leave for the night.”

Matina, my friend and frequent companion, had spent the evening with me as she often did, and I was glad to have her company. She’d been a permanent fixture at the Museum for four years that spring, having come from Doc Spaulding’s

Floating Palace,

the great boat circus that barged up and down the Mississippi. Her stage name back then was Annie Angel the Fat Girl, and although she no longer performed under that sobriquet, it suited her well. Matina was as charming as a beautiful child. With her blond finger curls, alabaster skin, and great blue eyes that gazed out at the world as if she were seeing it for the first time, she resembled a great big porcelain doll.

Flip sides of the same coin, we’d taken to each other the first time we met, and our friendship had only grown over the years, in spite of constant taunts from Ricardo the Rubber Man. “The woman weighs over three hundred pounds, Fortuno! And look at you. A stick figure! I’ll bet it slips in like a needle in the haystack.” I was mortified by such crass observations, especially when they were made in front of my lady friend, but everyone knew that Ricardo’s taunts had little truth to them. Matina had understood from the beginning that my body was not built for pleasure, and we’d both accepted the limitations of our relationship a long time ago. I liked to think our friendship was stronger because of it.

Earlier this evening, I’d spent an hour or so reading aloud from the current installment of

Our Mutual Friend

in

Harper’s

. Dickens’s fine wit made Matina smile, and she giggled like a girl as she put away her

lace and then plumped up the pillow on the sofa and tapped the seat next to her.

“Come look at my new discovery,” she said, digging into her bag and hauling out an oversized book. She flung it onto the low table in front of her, jangling the lamp as it landed. “It’s by the same man who wrote

Peter Parley’s Tales of America

. But this one is about people like us. I hear it goes back hundreds of years.”

The book, bound in black cloth and covered with fine embossing and gold letters, was titled

Curiosities of Human Nature

.

“He illustrates quite well, I think. Wouldn’t it be marvelous if someday we wound up in a book like this?”

The leaves of the book crackled as I thumbed through the pages. Matina was right; the woodcuts were of excellent quality. Although I vastly preferred my own books on congenital anomalies—Willem Vrolik’s

Handbook of Pathological Anatomy

or his more dramatic

Tabulae ad illustrandam embryogenesin hominis et mammaliam tam naturalem quam abnormem

—Matina’s new book was not a bad alternative. Her taste usually tended toward the pictorial—like most New York ladies, Matina kept an extensive collection of

cartes

not only of Prodigies and Wunderkinds but of famous New York families like the Schermer-horns and the Joneses—but at least she was literate.

Matina flipped through the pages of her new treasure one by one. “It’s quite comprehensive. Look here. He’s done a whole section on dwarfs. Jeffery Hudson, born in 1619, only three feet nine.” She furrowed her eyebrows and read out loud. “ ‘Midgets and dwarfs have generally one trait in common with children, a high opinion of their own little persons and great vanity.’ Ha!” She looked up, bright-eyed. “Well.

We

could have told him that!”

She was quite right. Over the years at least a dozen midgets had cursed us with their presence, and—with the exception of Tom Thumb and his lovely wife, Miss Lavinia—not one of them was tolerable. Dwarfs could be even worse—testy, arrogant, and impossible to please—but fortunately, Barnum rarely hired dwarfs. He thought them too misshapen for the delicate sensibilities of his feminine clientele.