The Tree In Changing Light (6 page)

Read The Tree In Changing Light Online

Authors: Roger McDonald

It is impossible to separate trees from people's attitudes about themselvesâtheir fears, their lack of self-acceptance, their timidity and their ignorance. But nothing is inflexible in human response. People can live and grow just as trees do, they can struggle and they can overcome what is in themselves. In Rockhampton, what was it that made people antitree? One thing is continuation of the pioneering spirit: a tree is there to be cut down. âBloody pioneers.' Well, that has gone too far, and the reaction needs to be fed back the other way. Tom Wyatt is feeding it back.

âSuch trees as he and his descendants planted showed

the desire in a new country for imprinting the values

of the old â¦'

T

HE QUIET

man bought a bulldozer and started clearing around his house. It was a big house like something from

Wuthering Heights

but in Australia. This wasn't the sort of clearing that left a landscape torn and desolate, ready for the plough. It was delicate, personal, attentive work he did on those clunking caterpillar treadsâedging the cold, heavy blade between trunks of old trees and plucking overgrown, dead and dying Monterey and Canary pines and setting them down in heaps. Around he went with this mechanised trowel. It was weeding on a big scale, a job (with time off from sheep-farming several thousand acres) that took a couple of years. He left other old trees intact although he didn't like them muchâthe Himalayan cypress, the photinia, the arbutus or Irish strawberry. It was a mix of growth common to old gardens in the Monaro, but some varieties were uncommon enough to make the garden at Cambalong noted for its raritiesâtrees and shrubs that would once have been planted on Indian hill stations. So here was an image of Scotland twice removed to the cool high country of south-eastern

Australia, in a wide grassy valley at six hundred and fifty metres. From a hill above the house the wild profile of the Snowy Mountains was visible one hundred kilometres to the north-west. Captain Ronald Campbell, a Loch Tay Scot who in 1831 first settled âBombalo' (later, when the town took that name, the property was renamed Cambalong) was ex-Indian army. Such trees as he and his descendants planted showed the desire in a new country for imprinting the values of the old. Robert Campbell comes along to reverse that trend, with reasons of his own that are like an expressive self-portrait.

The pines had grown shaggy and stark over more than a century, towering over the house, plunging it into dank shadows. When Robert and his English wife Henny took up residence in the late 1970s the homestead had been empty for twenty years. Now there were three daughters running through its many echoing rooms. The pines Robert attacked with his bulldozer were the other side of an argument he was having with the landscape. Here was a young family needing an expansive place to grow, not a place turned in on itself.

A couple of years previously Robert had planted four gum trees in front of the house,

Eucalyptus viminalis

, ribbon gums. They were the first of a large number he planned to put in, slender with pale creamy trunks and grey curling bark, pleasing to the eye and suited to the landscape. Up in the high gullies and ridges above Cambalong fantastic, shapely old ribbon gums had survived sheep and cattle. There were forest casuarinas there too, hardy as old iron left gnarled and isolated on the ridgelines. Many of them would have been growing before white settlement. There was a saying about native trees in Bombalaâwhere clear-felling of native forests

in the mountains towards the coast had left tens of thousands of hectares looking like the battlefields of the Sommeââif you planted any new ones you were a greenie'. What was a greenie anyway? It was hard to tell. Someone âdifferent', that was for sure. Someone who wasn't from Bombala. So where did Robert Campbell fit in?

He put a greenie sticker on his car.

Robert Campbell was born and raised at Bombala. His father gave him his first rifle at the age of six. He did correspondence school supervised by his mother. Whenever there was anything interesting happening on the property he was allowed to drop whatever he was doing and get involved. The things that fascinated him most were graders and bulldozers. At the age of twelve he experienced the shock-troop initiation of boarding school. Tudor House at Moss Vale was regimented but Cranbook in Sydney was better. His father had been there in the 1920s and gave Robert hints on how to get out of work. After leaving school he worked the property with his father and on the side started a trucking company. In his early twenties he hauled timber from the state forests around Bombala until his experience of forests laid waste by clear-felling sickened him. He did a lot of driving getting his work done, organising trucks and drivers, and keeping up with a social life. He liked good cars, he liked driving fast. When he went before a magistrate for a second speeding ticket in a short space of time he found himself in trouble. He was given three months' imprisonment.

Gaol? Just for speeding?

It was unthinkable. An appeal went before a judge. The judge was inflexible. The appeal went against him. Three months it was. Young men of good family had to be shown an example.

In Goulburn Gaol the screws told Robert Campbell they thought he shouldn't be in there for such a trivial offence, but when they saw his drivers coming to see him and discussing trucking company business they were resentful, and they locked him in maximum security. Robert Campbell will tell you it wasn't such a bad experience for someone who'd been at boarding schoolâliving among hardened criminalsâthat it was much the same. These were grown men who meant what they said. They looked you in the eye and you knew where you stood. They, too, in certain circumstances, you might imagine (if, say, they lived in Bombala), would have had the defiance to put a greenie sticker on their cars.

Â

In the cold air of the Monaro a red bull makes its way down a dusty hillside and crashes through a fence. Inside that fence is a garden planted more than a century ago. Dense shaggy pines and deciduous specimens formerly choking each other to death are tangled in windrows after the passage of the bulldozer blade. The red bull makes its way almost delicately through the mess, an invader from the drought-stricken paddocks. Riding the skies behind him are flocks of white cockatoos, five thousand and more wheeling and screeching.

Branches scrape muscled shoulders and scratch dribble-streaked, rough pink nostrils. The bull has something in mind. Between old buildings he comes on, trotting and swishing his tail, crashing past the weatherboard station-hands' cottages and the neglected stables, past the old-time cooks' rooms and maids' quarters, and along the high granite walls of the homestead until he stops.

He stands on a square of lawn. At the far side of the lawn, delicate in the cold light, are four high-country trees,

Eucalyptus viminalis

, ribbon gums, in front of the homestead where carriages used to draw up and early motor cars disgorged their travel-sick loads from Cooma. They are the first plantings inside the garden of species native to the landscape. The bull seems to have them in mind. Anyway that is the direction he is headed.

âThe tree's solitary unhappiness took on beauty and

almost sang, or at least cried out â¦'

Y

EARS AGO

the painter Tom Carment went to Zimbabwe and was so overwhelmed by the roaring spectacle of Victoria Falls that he turned his back on the boiling river and drew only one picture, a dung beetle struggling along a path.

Tom liked neglected places, unloved places, patches of earth the rest of us turned our backs on. In Australia he returned to them oftenâtangled bushland near West Head intersected by saltwater inlets; a bare paddock at Bombala dusted with frost; flat saltbush country under the Middleback ranges near Whyalla; a sandy patch of burnedover grasstrees near Perth; and to Sydney's eastern suburbs cemeteries, where in the boisterous southerlies hardly anything grew that didn't struggle, except where growth lurked in damp crevices fertilised by bones.

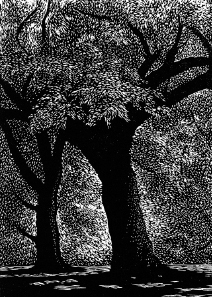

A lone Monterey pine grew in Botany Cemetery, in an industrialised part of the city near the airportâa coarsetrunked, badly lopped skeleton with a dangerous lean above jumbled headstones. Nobody cared for it much. Cemetery workers cut the tree back and muttered graveside warnings

about limbs falling on mourners. It appeared stalky in various lightsâlimbs snapped offâbleak in the blustery marine light of nearby Botany Bay, desperately sombre in the thick, rust-coloured haze of polluted mornings as container trucks roared past.

It was a tree marked for the chainsaw and Tom came to watch the light gather around it in skeins. A depressing tree, he admittedâwhich was why he liked it, he said, shrugging off my questions, not really having answers beyond what alerted his eye.

Months later, on gallery walls, images of the tree above those tilted headstones gave a sense of a lost forest's last remnant. The tree's solitary unhappiness took on beauty and almost sang, or at least cried out.

Tom painted at ground level with his brushes and pencils, the canvas flat on the dirt and his neck aching from looking up. Staying on to catch dark effects he was sometimes benighted after a painting day, feeling his way home along barbed wire fences, clambering up rocky gullies. Carrying his work he delicately negotiated his steps to stop the wet panel brushing foliage. Once he fell and found himself sprawled, dazed, unable to move for fifteen minutes or so, wondering if that was his end. Even in daylight sometimes he got lost walking home. The bush was like that, in Australia, bewildering. Getting lost was a theme in colonial painters' work as they struggled to claim strangeness. It was still what painters did. Early mornings found Tom going out in an old army greatcoat with the frost on his back, setting up to watch a particular tree declare itself in the dawn fog.

When Tom found a place that felt right, a tree or a thicket

of trees, he prowled around for up to half an hour like a dog deciding where to sit. At West Head scarred, burnt, anarchic processes of growth filled his workspace. There was hardly ever any greenâjust bushfire-scorched blacks, ant-reds, subdued silvers, dappled greys. Grabbing a handful of fresh charcoal after the bushfire had been through he drew with the material of the subject itself.

But then, months after the fires were gone, green explodedâso many small new shoots sprouting from charred trunks that the bud colour took on a massed effect, thickening the nature of light itself as if through a prismâgreen tinged with growth-tip red. Some time later still, after rain and another summer, Tom returned to where the fires had been and looked for the tree he'd painted time and again. The tree was lost in regrowth. It had shadowed onto his canvas and then grown back into the mass of trunks and branches where he once found it.

Tom squatted on a rocky bank overlooking dappled-green, sandy-bottomed salt water. He insisted on going painting alone, with no-one to distract him from the urgent rush of work. (To recapture what he did we sat in a darkened basement room with a slide projector humming.) The thin-trunked trees in the foreground cut the frame into strips and intensified the wateriness beyond them. It was light coming through the trees as much as the trees themselves that drew him.

I wondered if trees to a painter were comparable with how they were in botanyâsolidified sunlight through the growth-engine of photosynthesisâa texture of light made three-dimensionally weighty. Was a painter of trees returning trees to the light they came from? Enhancing the gift? Was

imagination praise? Was it what was meant by prayer, except secularised within understandable limits?

Tom never cared about the names of trees, never minded how trees were otherwise defined, what their botanical names were, or why they grew where they grew, or how. He remembered Krishnamurti's guiding idea from the age of eighteen, when he first read it: âWhen you name something you think you've seen it.' The light around the trees he painted had an emotional content, he said, and that was what it was for him.

It was interesting. He could no more give a name to that emotional content than he could give a name to the trees.