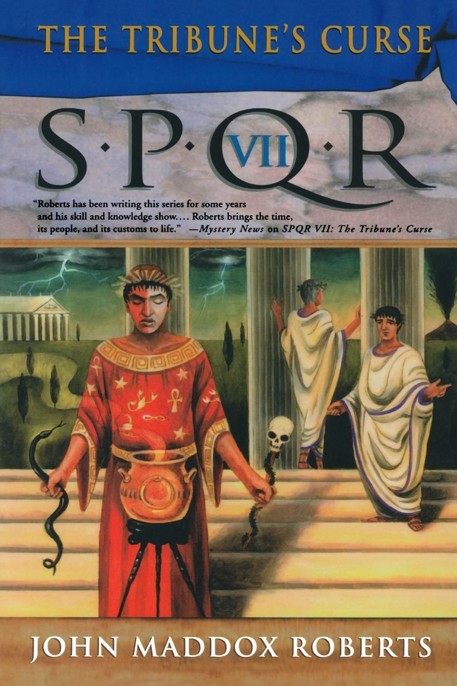

The Tribune's Curse

Read The Tribune's Curse Online

Authors: John Maddox Roberts

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Historical

SPQR VII

THE

TRIBUNE’S

CURSE

SPQR

Senatus PopulusQue Romanus

The Senate and People of Rome

Also by

JOHN MADDOX ROBERTS

SPQR Series

SPQR I: The King’s Gambit

SPQR II: The Catiline Conspiracy

SPQR III: The Sacrilege

SPQR IV: The Temple of the Muses

SPQR V: Saturnalia

SPQR VI: Nobody Loves a Centurion

The Gabe Treloar Series

The Ghosts of Saigon

Desperate Highways

A Typical American Town

SPQR VII

TRIBUNE’S

CURSE

JOHN MADDOX ROBERTS

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS

ST. MARTIN’S MINOTAUR

NEW YORK

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS

.

An imprint of St. Martin’s Press.

SPQR VII: THE TRIBUNE’S CURSE. Copyright © 2003 by John Maddox Roberts. All

rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may

be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission

except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roberts, John Maddox.

the Tribune’s curse: SPQR VII / John Maddox Roberts.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-30488-9

1. Metellus, Decius Caecilius (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Rome—History—Republic, 265–30 B.C.—Fiction. 3. Private investigators—Rome—Fiction. I. Title: SPQR 7. II. Title: Tribune’s curse. III. Title.

PS3568.O23874 S68 2003

813'.54—dc21

2002032509

First Edition: March 2003

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Susan Shortt

For years of friendship and good conversation

Contents

I

WAS HAPPIER THAN ANY MERE

mortal has a right to be, and I should have known better. The entire body of received mythology and every last Greek tragedy ever written have made one inescapable truth utterly clear: If you are supremely happy, the gods have it in for you. They don’t like mortals to be happy, and they will make you pay.

The reason for my happiness was that I wasn’t in Gaul. Nor was I in Parthia, Greece, Iberia, Africa, or Egypt. Instead, I was at the center of the world. I was in Rome, and for a Roman there can be no greater joy than to be at home, where all roads famously lead. Well, if you can’t be in Rome, Alexandria isn’t a bad second choice, but it just isn’t Rome.

Not only was I in Rome, but I was in the Forum, where all those roads converge near the Golden Milestone. It really isn’t golden, just touched up with a bit of gilding, but I’ll take it over any gaudy barbarian monument any day. And it was a beautiful day, which always helps. And I was standing for office, which I

was going to win. I knew I was going to win because, when we men of the

gens

Caecilia Metella demanded high office, we got it.

There was one tiny, minute flaw in my perfect happiness. The office I was standing for was aedile. Now, constitutionally, the aedileship was not strictly on the

cursus honorum

, that ladder of public office one had to ascend one rung at a time to reach the highest offices of praetor and consul, where the greatest honor was, and their subsequent propraetorial and proconsular commands, where all the loot was to be had.

The aediles were loaded with responsibilities concerning the conduct and welfare of the City. They had charge of the markets, of upkeep of the streets and public buildings, enforcement of the building codes, the supervision of public morals (that was always good for a laugh), and all the other duties nobody else could be persuaded to perform.

The aediles were also in charge of the public Games, and the state provided only a ridiculously small allotment for those necessary but horrendously expensive spectacles. Which meant, if you wanted to put on really spectacular Games, you had to pay for them out of your own purse. That meant, if you weren’t tremendously rich, you borrowed and ended up in debt for years.

So why, you might ask, would anybody want this onerous office if it wasn’t constitutionally required? For the simple reason that the electorate had become accustomed to receiving fine spectacles from their aediles, and if your Games weren’t suitably splendid, they would not elect you to the praetorship.

This unpleasant necessity of public life had been turned to unexpected advantage by Caesar, who, as aedile, incurred such tremendous debts that everyone assumed he had foolishly ruined himself in order to win favor with the mob. Then, much to their astonishment, some of the most important men in Rome woke up to discover that, if they were to have any hope of recovering their loans, they had to push Caesar into higher office so he could get

rich. It worked neatly for Caesar, but it meant that the voters were now accustomed to an even more lavish standard in Games: more days of races, more comedies and dramas, more public feasts, and, most important, more and better gladiators. Where once a showing of twenty pairs from the local schools had been considered a good show, people now expected four or five hundred pairs of the best Campanian swordsmen tricked out in plumes and gilded armor. None of this was cheap.

But all such dismal prospects were far from my mind as I stood in the Forum on a perfect day in early fall when Rome and all of Italy are at their most lovely. The sky was cloudless; the smoke from the altars ascended straight toward the heavens; there were flowers blooming everywhere. The oppressive heat of summer was past, and the rains, clouds, and chill of winter were still far away. With the other office seekers I wore a specially whitened toga, the

candidus

, so everyone would know who we were, just standing there like fools and saying nothing.

By ancient law, a candidate was forbidden to canvass for votes. He had to stand in one spot and wait for someone to come up and speak to him, at which time he could wheedle for all he was worth. Of course, each candidate was accompanied by his clients, who acted as a sort of cheering section, always gazing admiringly at him, accosting passersby, and telling them all about what a fine fellow their patron was.

I suppose it all looked rather ludicrous to foreigners, but it was an agreeable way to spend your time when the weather was good, especially if you had just escaped Gaul and Caesar’s huge and bloody war there. Caesar had granted me leave of absence so that I could come home to stand for office, with the agreement that I would return as soon as I had served my year. Well, we would see about that. Caesar could be dead before then, the war a disaster. This was the result for which his enemies prayed and sacrificed daily to Jupiter Best and Greatest.

But the war was far away, the weather was fine, I was fulfilling my Caecilian heritage by standing for office, it would be months before I had to present my feasts, my

ludi

and my

munera

, and all was right with the world. I was relatively safe from the mobs of my old enemy, Clodius, because he was Caesar’s flunky and I was newly married to Caesar’s niece, Julia. I should have seen the trouble coming—not that it would have made much difference if I had. And the day started out rather well, too.

The first man to approach me was my distinguished but tediously named kinsman, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica. With that much name you would have expected a bigger man, but he was rather slight, and a Caecilian by adoption, not that this meant much. All our great families were so intermarried that we all bore much the same degree of consanguinity, whatever name we happened to bear.

“Good morning, Scipio,” I said as he walked up to me. “Are you on support duty today?” It was understood that, since I was standing for office, the most distinguished men of the family would show themselves in my company from time to time. Scipio was one of that year’s praetors, but he was not accompanied by his lictors. He was also a

pontifex

, and that morning he wore his pontifical insignia, so I knew he was on his way to a formal religious event.

“A meeting of the Pontifical College has been called,” he said. “I thought I would stop by and lend you an aura of much-needed respectability.” My reputation in the family did not stand high.

“Will a ruling by the

Pontifex Maximus

be required? He’s out of town, you know.” The holder of that ancient office was, of course, Caesar himself, and he was off on his extraordinary five-year command in Gaul.

“I certainly hope not. It’s a difficult question under discussion. We may have to call a conclave of all the priestly colleges

in Rome.” He didn’t look as if he were looking forward to it.

“The

flamines

, the Arval Brotherhood, the

quinquidecemviri

, and the Vestals and all the rest? But that’s only been done in times of grave emergency. Has something happened the rest of us haven’t heard about yet? Have Caesar and his legions been annihilated, and are the Gauls marching on Rome?”

“Keep your voice down, or you’ll start rumors,” he cautioned. “No, it’s nothing like that. A matter of religious practice, and I’m not permitted to talk about it.”

Throughout this we grinned at one another like apes, so that anyone watching would see in what high esteem the distinguished

pontifex

held the lowly but dutiful and conscientious candidate who, in the best tradition of the Republic, sought to assume the heavy burdens of office. This was being repeated, with variations, all over the end of the Forum where the office seekers congregated.