Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

The Triumph of Seeds (4 page)

F

IGURE

1.3. Domesticated in Mexico and Central America over 9,000 years ago, avocados were long established in local diets by the time of the Aztec feast pictured here. Anonymous (Florentine Codex, late sixteenth century). W

IKIMEDIA

C

OMMONS

.

In a brilliant piece of casting work, the title role for the movie

“Oh, God!”

went to George Burns. When asked about his greatest mistakes, the Burns-almighty deadpanned a quick response, “Avocados. I should have made the pits smaller.” Sous-chefs in charge of guacamole would certainly agree, but to botany teachers around the world, the avocado pit is perfect. Inside its thin brown skin, all the elements of the seed are laid out in large format. Anyone wanting a front-row seat for a lesson on germination needs nothing more than a clean avocado pit, three toothpicks, and a glass of water. The simplicity of it was not lost on early farmers, who domesticated the avocado at least three different times from the

rainforests of southern

Mexico and Guatemala. Long before the rise of the Aztecs or the Mayans, people in Central America already enjoyed a diet rich with the creamy flesh of avocado. I enjoyed it, too, binging on a spree of delicious sandwiches and nachos in preparation for my experiment. With a dozen fresh pits and a handful of toothpicks, I headed for the Raccoon Shack to get started.

The Raccoon Shack sits in our orchard, an old shed sided with tar paper and scrap lumber, and named for its former inhabitants. The raccoons once made an easy living there, gorging themselves on our apple harvest every fall. We had to give them notice, however, when parenthood suddenly required me to find an office space outside the confines of our small home. The shack now boasts power, a woodstove, a hose spigot, and plenty of shelf space—everything I might need to coax my avocados to life. But I wanted more than germination; I knew to expect roots and greenery. What I needed was to understand just what inside that seed was making it all happen, and how such an elaborate system evolved in the first place. Fortunately, I knew just the people to talk to.

Carol and Jerry Baskin met on the first day of graduate school at Vanderbilt University, where they both enrolled to study botany in the mid-1960s. “We started dating right away,” Carol told me, so they were seated next to one another when the professor came around assigning research topics. In pairs. “That was special because it was the first time we worked together,” she remembered. It also marked the first time they turned their minds to a topic that would define their careers. Though they insist that their romance was typical—mutual friends, similar interests—there has been nothing standard about the intellectual partnership it fostered. Carol finished her doctorate a year ahead of Jerry, but they’ve been pretty much in synch ever since, publishing more than 450 scientific articles, chapters, and books on seeds. For a guided tour of an avocado pit, no one on the planet could have better credentials.

“I tell my students that a seed is a baby plant, in a box, with its lunch,” Carol said at the start of our conversation. She speaks with

a southern drawl and has a casual way of explaining things, talking around the edges of difficult concepts until the answers seem to reveal themselves. It’s easy to see why students rank her among the best science teachers at the University of Kentucky. I reached Carol by phone in her office, a windowless room where piles of papers and books cover every surface and overflow into the lab next door. (Jerry had recently retired from the same department, which apparently involved moving his piles of books and papers home to their kitchen table. “There are just two little clear places where we eat,” Carol laughed. “It’s a problem if we want to have company.”)

With her “baby in a box” analogy, Carol neatly captured the essence of seeds: portable, protected, and well-nourished. “But because I’m a seed biologist,” she went on, “I like to take things a step further: some of those babies have eaten all their lunch, some have eaten part of it, and some haven’t even taken a bite.” Now Carol opened a window onto the kinds of complexities that have kept her and Jerry fascinated for nearly five decades. “Your avocado pit,” she added knowingly, “has eaten all of its lunch.”

A seed contains three basic elements: the embryo of a plant (the baby), a seed coat (the box), and some kind of nutritive tissue (the lunch). Typically, the box opens up at germination, and the embryo feeds on the lunch while it sends down a root and sprouts up its first green leaves. But it’s also common for the baby to eat its lunch ahead of time, transferring all of that energy to one or more incipient leaves called

seed leaves

, or

cotyledons

. These are the familiar halves of a peanut, walnut, or bean—embryonic leaves so large they take up most of the seed. As we were talking, I plucked an avocado pit from the pile on my desk and split it open with my thumbnail. Inside, I could see what she meant. The pale, nut-like cotyledons filled each half, surrounding a tiny nub that held the fledgling root and shoot. For a seed coat, the pit offered little more than varnish—thin, papery stuff that was already flaking off in brown sheets.

“Jerry and I study how seeds interact with their environment,” Carol said. “Why seeds do what they do when they do it.” She went

on to explain that the avocado’s strategy is somewhat unusual. Most seeds dry out as they ripen, using a thick, protective coat to keep moisture at bay. Without water, the embryo’s growth slows to a near standstill, a state of arrested development that can persist for months, years, or even centuries until conditions are right for germination. “But not avocados,” she warned. “If you let those pits dry out, they’ll die.” The way Carol said this reminded me that my avocado pits were living things. Like all seeds, they are live plants that have simply put development on pause, waiting until they land in just the right place, at just the right time, to send down roots and grow.

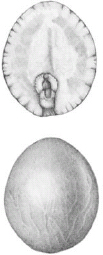

F

IGURE

1.4. Avocado (

Persea americana

). Inside the paper-thin seed coat of an avocado pit, two massive seed leaves surround a tiny nub containing the root and shoot. Avocados evolved in a rainforest, where young trees need a large dose of seed energy to sprout and get established in deep shade. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

For an avocado tree, the right place is somewhere its seeds will never desiccate and the season is

always right for sprouting. Its

strategy relies on constant warmth and dampness, conditions you might find in a tropical rainforest—or suspended over a glass of water in the Raccoon Shack. With no need to survive long droughts or cold winters, avocado seeds take only the briefest pause before trying to grow again. “The avocado’s dormancy may simply be the time necessary for the process of germination to take place,” Carol explained, “which shouldn’t be all that long.”

I tried to keep that in mind during the slow weeks before my avocado pits showed any signs of life. They became my silent, unchanging companions: two rows of mute brown lumps lined up on a bookshelf below the window. Although I have an advanced degree in botany, I also have a long history of killing houseplants, and I began to fear for them. But like any good scientist, I took comfort in data, filling an elaborate spreadsheet with numbers and notes. Though nothing ever changed, there was a certain satisfaction in handling every seed, dutifully monitoring its weight and dimensions.

When it happened, I didn’t believe it. After twenty-nine inert days, Pit Number Three gained weight. I recalibrated the scale, but there it was again, the most encouraging

tenth of an ounce I’ve ever measured. “Most seeds take up water right before they germinate,” Carol confirmed, a process cheerfully known as

imbibing

. Why it often takes so long is the subject of debate. In some cases, water may need to breach a thick seed coat or wash away chemical inhibitors. Or the reason may be more subtle—part of a seed’s strategy to differentiate brief rain showers from the sustained dampness necessary for plant growth. Whatever the reason, I felt like pouring a libation for myself as, one after another, all my avocado pits began doing it. Outwardly they looked the same, but inside, something was definitely going on.

“We know a little bit about what’s happening in there, but not everything,” Carol admitted. When a seed imbibes, it sets off a complex chain of events that launches the plant from dormancy straight into the most explosive growth period of its life. Technically,

germination

refers only to that instant of awakening between water uptake and

the first cell expansion, but most people use the term more broadly. To gardeners, agriculturalists, and even the authors of dictionaries, germination includes the establishment of a primary root and the first green, photosynthetic leaves. In that sense, the seed’s work isn’t done until all of its stored nutrition is used up—that is, transferred to an independent young plant capable of making its own food.

My avocados had a long way to go, but within days the pits began splitting apart, their brown halves tilted outward by the swelling roots within. From a tiny nub in the embryo, each primary root grew at an astonishing pace—a pale, seeking thing that plunged downward and tripled in size in a matter of hours. Long before I saw any hint of greenery, every pit boasted a healthy root stretching to the bottom of its water glass. This was no coincidence. While other germination details vary, the importance of water is constant, and young plants place top priority on tapping a steady source. In fact, seeds come prepackaged for root growth—they don’t even need to make new cells to do it. That may sound hard to believe, but it’s similar to what clowns do with balloons all the time.

Scrape the side of a fresh avocado root, and you’ll get thin, curly strips like the radish shavings on a fancy salad. I placed one of these under my microscope and saw lines of root cells in sharp relief—long, narrow tubes that looked a lot like the balloons a clown might use to tie animal shapes. And just like a clown, the embryonic roots stuffed inside of seeds know that you don’t show up to a party with your balloons already inflated. Even oversized clown pockets couldn’t possibly hold enough. Empty balloons, on the other hand, take up no space at all and can simply be filled with air (or water) whenever and wherever the need arises.

The difference in size between empty and inflated balloons is actually quite astounding. A standard package of “Schylling Animal Refills” from my local toy store contains four greens, four reds, five whites, and assorted blues, pinks, and oranges, for a total of twenty-four balloons. Deflated, they fit easily into my cupped hand: a bright, rubbery bundle less than three inches (seven and one-half

centimeters) across. Once I began blowing them up, I quickly appreciated why any good clown also travels with a helium tank or a portable air compressor. Lightheaded and wheezing, I tied the last balloon forty-five minutes later and sat surrounded by a riot of color. The balloons now formed a squeaking, unruly pile four feet (one and one-quarter meters) long, two feet (sixty centimeters) wide, and a foot (thirty centimeters) tall. Lined up end to end, they stretched from my desk out the door, across the orchard, through the gate, and onto the lane, for a total of ninety-four feet (twenty-nine meters). Their volume had risen by a factor of nearly 1,000, with the potential to form a skinny tube 375 times longer than the rubbery ball I’d started with—all from the addition of air. Give water to a seed, and its root cells will fill to do virtually the same thing, stretching longer and longer as they inflate. The process can last for hours or even days—a massive burst of growth before the cells at the tips even bother dividing to make new material.

Seeking out water is an understandable plant priority. Without it, growth stalls, photosynthesis sputters, and nutrients can’t be liberated from the soil. But seeds can have subtler reasons to start growing this way, and no example makes that case better than coffee. As everyone with an early-rising toddler knows, coffee beans contain a potent and very welcome blast of caffeine. But while it may be stimulating to weary mammals, caffeine is also known for getting in the way of cell division. In fact, it stops the process cold, a tool so effective that researchers use caffeine to manipulate the growth of everything from spiderworts to hamsters. In a coffee bean, this trait does wonders to maintain dormancy, but it poses a distinct problem when it’s finally time to germinate. The solution? Sprouting coffee seeds shunt their imbibed water to both root and shoot, swelling them rapidly to propel their growing tips safely away from the

stifling effects of the caffeinated bean.

Avocado pits contain a few mild toxins to ward off pests, but nothing that slows things down once the game is afoot. I watched the roots grow and branch for days before the first greenery appeared,

a tiny shoot emerging from the widening crack at the top of each pit. “It’s accurate to call the next phase a massive transfer of energy from the cotyledons,” Carol told me, explaining how what started out as the seed’s “lunch” would now fuel a surge of upward growth. Within a few weeks, I found myself the caretaker not of seeds, but of saplings, young trees that bore little resemblance to the pits I’d nurtured for months. As a parent, I was reminded of the many transformations I’d already witnessed in young Noah’s life, and something that Carol had mentioned suddenly struck me. Early in their careers, she and Jerry had decided they were just too busy to have children. In studying seeds, I now realized, they had nonetheless devoted themselves to the fickle lives of babies.