The Trojan War

Authors: Barry Strauss

The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved

Greeceâand Western Civilization

What If ?: The World's Foremost Military Historians Imagine

What Might Have Been

(contributor)

Western Civilization: The Continuing Experiment

(with Thomas F. X. Noble and others)

War and Democracy: A Comparative Study of the Korean War

and the Peloponnesian War

(with David McCann, co-editor)

Rowing Against the Current: On Learning to Scull at Forty

Fathers and Sons in Athens: Ideology and Society

in the Era of the Peloponnesian War

Hegemonic Rivalry: From Thucydides to the Nuclear Age

(with Richard Ned Lebow, co-editor)

The Anatomy of Error: Ancient Military Disasters

and Their Lessons for Modern Strategists

(with Josiah Ober)

Athens After the Peloponnesian War: Class, Faction and Policy, 403â386

B.C.

S

IMON AND

S

CHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2006 by Barry S. Strauss

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

S

IMON

& S

CHUSTER

and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Dana Sloan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Strauss, Barry S.

The Trojan War : a new history / Barry Strauss.

p. cm.

Includes biographical references and index.

Contents: War for HelenâThe black ships sailâOperation beachheadâAssault on the wallsâThe dirty warâAn army in troubleâThe killing fieldsâNight movesâHector's chargeâAchilles' heelâThe night of the horse

1. Trojan War. I. Title.

BL793.T7S78 2006

939'.21âdc22

2006044389

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-9362-4

ISBN-10: 0-7432-9362-2

Map of Troy

from

Celebrating Homer's Landscapes: Troy and Ithaca Revisited

by J. V. Luce, Yale University Press, page 94, © 1998, used by permission.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

For Scott and Karen, Judy and Jonathan,

Larry and Maureen, and Ronna and Richard

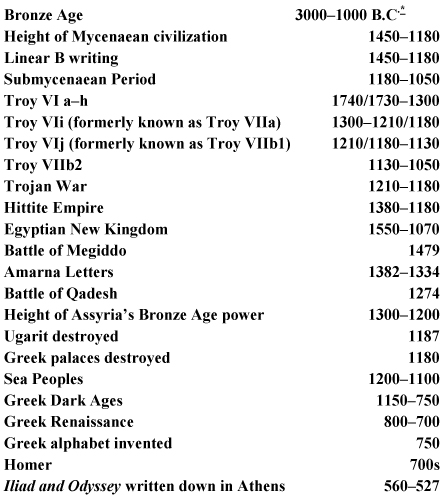

Timetable of Events Relating to the Trojan War

A Note on Ancient History and Archaeology

Chapter Two: The Black Ships Sail

Chapter Three: Operation Beachhead

Chapter Four: Assault on the Walls

Chapter Six: An Army in Trouble

Chapter Seven: The Killing Fields

M

ost of the quotations from the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

are from Alexander Pope's translation. A few have been translated by the author for greater accuracy.

Homer never uses the word “Greeks,” referring instead to Achaeans, Danaans, Argives, and, occasionally, Hellenes. Modern scholars refer to the Greeks of the Late Bronze Age as Mycenaeans. This book generally refers to them as Greeks.

All dates in this book from the Bronze Age (ca. 3000â1000

B.C.

) are approximate unless otherwise stated.

to the Trojan War

*All dates are approximate.

and Archaeology

A

ncient Greek history traditionally begins in the year 776

B.C.

, when the first Olympic Games are supposed to have been held. By coincidence, the earliest example of the Greek alphabet dates to about 750

B.C.

So both tradition and scholarship would agree in labeling everything that happened before the early eighth century

B.C.

in Greece as “prehistory.” But thanks largely to archaeology, we know a great deal about the history of the “prehistoric” Greeks. And some of our knowledge even comes from written sources, because centuries before the Greek alphabet, scribes used a primitive writing system for record-keeping in Greek. Called Linear B, it was in use from about 1450 to about 1180

B.C.

, after which it disappeared. Much more sophisticated writings also survive from other so-called prehistoric cultures, and they offer important historical information about prehistoric Greece.

But more on that later. First, let us quickly scan the historic period of ancient Greece. The Greek city-states reached their heyday in the centuries between about 750 and 323

B.C.

The period between 750 and 480 is known as the Archaic Age, while the years from 480 to 323 are called the Classical Period. At the end of the Classical Period, King Alexander III of Macedon, known today as Alexander the Great, conquered all of Greece as well as the Persian Empire to the east. Alexander's conquests began a new era of Greco-Macedonian kingdoms known as the Hellenistic Age, 323â30

B.C.

That gave way, in turn, to the Roman Empire, which lasted until

A.D.

476, when it split into barbarian kingdoms in the West and the Byzantine Empire in the East.

Almost all ancient written testimonies about the Trojan War date to the 1,200-year period from the start of the Archaic Age to the end of the Roman Empire. But in order to understand what really happened, we must look backward. The four centuries before the start of the Archaic Age are known collectively as the Greek Dark Ages (ca.1150â750

B.C.

). “Dark” refers to the absence of writing, but the physical evidence uncovered by archaeologists sheds light on that era.

Another important term is Iron Age, used for the millennium from about 1000

B.C.

to

A.D.

1. In this epoch, new technology made iron the most durable metal for tools and weapons. The earlier two millennia, from about 3000 to about 1000

B.C.

, are known as the Bronze Age, after that era's most widespread metal for tools and weapons; iron was known but rare. The Bronze Age is the setting for this book.

In Greece, the Bronze Age is commonly divided into three periods, Early (3000â2100

B.C.

), Middle (2100â1600), and Late (1600â1150). Naturally, it is difficult to assign dates to events that took place so long ago. Most dating is relative and approximate rather than absolute: that is, we can say that A is older than B or even that A comes from the period of, say, 1600â1500

B.C.

, but rarely can we be more specific.

Sometimes we get help from surviving written records, such as lists of Egyptian kings and their reigns (although even in that case we are not completely sure about dating). On occasion we hear of an eclipse, which can be dated by astronomers. In rare instances, it is possible to find samples of once-living material (from bone to shells to minerals) that can be dated by laboratory testing through radiocarbon dating, neutron activation analysis, or dendrochronology (counting tree rings, based on tree physiology as well as on rainfall and other environmental factors). By the last technique, for example, the tremendous volcanic explosion that destroyed most of the island of Thera has been dated to 1627â1600

B.C.

But these cases are few and far between because they depend on the quality of the sample and because testing is very expensive. Dendrochronology requires having both a number of comparative ancient tree samples as well as having nearby living trees with identical ring patterns to the sample in question. And radiocarbon testing can narrow dating to about a century but not a year.

So most dating of material dug out of the earth has to be done by more rough-and-ready methods. Fortunately for historians the remains of past civilizations tend to be deposited in layers. For example, if a house is built in

A.D.

1700 and then torn down and replaced in 1800, the remains of the old house will be located below the remains of the new house. Any glass, wood, bricks, artwork, or other material found together with the foundations of the old house can be dated to the period 1700â1800. If we could take a “slice” of history in the soil of an ancient land, like Greece, we would find layers of history stacked up one above the other. The technical name for these layers is strata, and the careful study of them is called stratigraphy. Stratigraphy is one of the most important tools in the archaeologist's kit for assigning dates.

The city of Troy, for example, consists of a dozen separate levels in the Bronze Age. Each corresponds to the city during a particular era. Troy I, for example, is the city as it was ca. 3000â2600

B.C.

, while Troy VIi (formerly called Troy VIIa) is the city of ca. 1300â1180

B.C.

The division between two layers is sometimes sharp and sometimes barely distinct. For example, there is relatively little difference between Troy VIh (ca. 1470â1300

B.C.

) and Troy VIi but Troy VIj (ca.1180â1130

B.C.

and formerly called Troy VIIb1) was very unlike Troy VIi, which it followed.

The most common item found in the layers of ancient civilization is pottery. By carefully tracing changes in the shapes and styles of pottery, and by vigilantly recording the layer in which a particular potsherd is found, experts can date archaeological strata, sometimes fairly narrowly, to as little as a generation.

Through a combination mainly of pottery analysis and stratigraphy, scholars have devised a system of relative dating for the Greek Bronze Age. Anchored by a few absolute dates, the periods known as Early, Middle, and Late Helladic are the building blocks for dating Greek prehistory. They are subdivided in turn into such subperiods as Middle Helladic III, Late Helladic IIB1.

Pottery dating is sometimes specific to a particular region, and these periods apply mainly to the Greek mainland and islands. In Anatolia, where Troy is sited, pottery dating is based on locally produced pottery, much of it imitations of the popular and widely traded pottery of Greece. So Trojan pottery dating differs from Greek.

Archaeology is mostly a matter of digging in the soil, but it can also mean going beneath the sea. Underwater archaeology in the Mediterranean has exploded with dramatic discoveries in the last few decades. For the background to the Trojan War, three Bronze Age shipwrecks, two off the coast of Turkey and one off the coast of Greece, stand out in importance. The Ulu Burun wreck (Turkey), a ship of about 1300

B.C.

, the Cape Gelidonya wreck (Turkey), and the Point Iria wreck (Greece) each date to about 1200

B.C.

; all offer intriguing evidence.

With so many factors involved, dating events in the Bronze Age is complicated and often controversial. Consider these as rough guides: From about 2000 to 1490

B.C.

, civilization flourished on the island of Crete. Organized around several great palaces, this civilization is known today as Minoan. The Minoans were great farmers, sailors, traders, and artists. Although their ethnicity is not clear, we do know that they were not Greek.

The first speakers of Greek arrived in Greece from points east around 2000

B.C.

They were a warlike people and took over the Greek peninsula from its earlier inhabitants. In the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600â1150

B.C.

) the newcomers' civilization dominated Greece in a series of warrior kingdoms, of which the most important were Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns, and Pylos. We call their civilization Mycenaean. Linear B (a writing system representing syllables) shows that their language was Greek, and that they worshipped the same gods as their Archaic and Classical Greek descendants. In short, they were Greek. Evidence suggests that the Mycenaeans called themselves Achaeans or Danaans, the two terms which, along with Argives, Homer uses for them. New Kingdom Egyptian texts refer to the kingdom of “Danaja” and to such cities in it as Mycenae and Thebes. This is independent confirmation of Homer's political framework.

The Mycenaeans were sailors, soldiers, raiders, and traders. Around 1490

B.C.

they conquered Minoan Crete and took over its former colonies in the eastern Aegean islands and on the Anatolian mainland (present-day Turkey) at Miletus. Over the next several centuries, they engaged in war, diplomacy, commerce, cultural exchange, and dynastic intermarriage with the great kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean. At least one king of Ahhiyawa was addressed as an equal in diplomatic correspondence from the Hittite king. Although Linear B texts do not allow the identification of specific events, they provide an abundance of data about weapons and warfare. If the Trojan War really happened, it was an event in the Mycenaean Ageâone of the last great events before the decline and fall of Mycenaean civilization in the 1100s

B.C.

The Mycenaeans' main rival was the greatest kingdom in Anatolia, Hatti, also known today as the Hittites. The Great King of the Hittites was important enough to correspond on an equal footing with the rulers of Assyria, Babylon, Mitanni, and Egypt and powerful enough to make war on them. These six kingdoms were the perennial powers of the region in the Late Bronze Age.

From their stronghold high in the central Anatolian plateau, the big city of Hattusha, the Hittites looked down and competed for the rule of what was then the world. Their main interest was in expanding southward to the Mediterranean coast of Anatolia and eastward into Syria. But they found themselves drawn willy-nilly into the ever-shifting politics of western Anatolia. Thanks to the evidence of archaeology and epigraphy, this story is much richer than most people would guessâbut largely untold.

The most important source is the Hittite royal archives from Hattusha, from which thousands of clay tablets survive, as do hundreds of similar tablets from other Hittite cities. Most of them are written in the Hittite language, in a writing system called cuneiform, which employs about five hundred wedge-shaped symbols. We also have Hittite inscriptions from various places carved on stone or inscribed on metal. Some of these are written in hieroglyphics, a rebuslike system of picture-writing, but not in the famous Egyptian hieroglyphics: rather, they are written in a language called Luwian. Luwian is closely related to Hittite and was spoken widely in southern and western Anatolia. Luwian survived the Bronze Age, and we have Luwian inscriptions as late as the 200s

A.D.

Another related Bronze Age Anatolian language is Palaic, spoken in northwestern Anatolia. Little Palaic writing survives.

Other writing systems also existed in the eastern Mediterranean in the Bronze Age. Akkadian, originally a language used in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), was the international language of diplomacy. Akkadian tablets survive from Cyprus; from Ugarit, a merchant city on the coast of northwest Syria; from Amurru, a border state between the Hittites and Egypt; and from Egypt itself. In addition, texts from the powerful city of Mari (1800â1750

B.C.

) abound in information about warfare, although they predate the Trojan War by about five hundred years, so they should be used cautiously. Akkadian inscriptions from the Assyrian Empire of the 1200s

B.C.

are also a big source of evidence about conflicts and combat, and they are roughly contemporaneous with the Trojan War.

Turning to the Levant, the so-called Amarna Letters (most from 1382â1334

B.C.

) are a collection of communications among eastern Mediterranean princes, especially between Pharaoh and his Canaanite vassals. These letters amply document diplomacy and war, especially small wars and low-intensity conflicts. The letters show that the years between about 1450 and 1250 mark the first international system of states in history. For their part, the warrior-pharaohs of New Kingdom Egypt (1550â1070

B.C.

) have left a trove of information about military matters.

Finally, various epic poems, myths, and prayers survive from the ancient Near East, from the Sumerian

Gilgamesh

to the Ugaritic

Kirta,

and many are relevant to our story. Although some date to 2000

B.C.

or earlier, they reveal continuing behaviors and technologies.

There were various kingdoms in western Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age, but for us, by far the most important was Wilusa. The subject of international conflict and civil war, Wilusa is accepted by many scholars as the place the Greeks called first Wilion and then Ilionâthat is, Troy.

Troy was a great city for the two thousand years of the Bronze Age, from about 3000 to 950

B.C.

After being abandoned near the beginning of the Iron Age, Troy was resettled by Greek colonists around 750

B.C.

and remained a small Greek city throughout antiquity. Wave after wave of different peoples lived in Bronze Age Troy. None of those populations is easily identifiable today, but all left signs of wealth, power, and sometimes tragedy. The city was destroyed from time to time by fire, earthquake, and war, and then rebuilt. The ruins have yielded gold, artistic treasures, and palatial architecture. In the Late Bronze Age, Troy was one of the largest cities around the Aegean Sea and a major regional centerâeven if not nearly as large as the great cities of central Anatolia, the Levant, or Mesopotamia. Late Bronze Age Troy controlled an important harbor nearby and protected itself with a huge complex of walls, ditches, and wooden palisades. If any period of Troy corresponds to the great city of the Trojan War, this was it.