The Two of Us (23 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

Despite being the fall guy or doll for many of his jokes, Pauline was devoted to John and he to her. On set she learned to

prompt him with a gentle ‘Did you mean to say that?’ rather than ‘You got that line wrong.’ If he had no faith in the current

director, after a scene he would look at Pauline for a nod of approval or a signal that ‘No, you could do better.’ He trusted

all of them implicitly.

Beneath the surface jollity, the people closest to him suspected he was in a bad way. John Madden reckoned that John only

felt safe when acting. He could control emotions when he acted them. Real ones were messy. Madden directed an episode of

Morse

set in Australia. John asked me to go with him but I refused while he was still drinking. I was frightened of being isolated

with him away from home while his attitude towards me was so volatile. He was distraught at my refusal and his misery was

converted into one of the most effective scenes ever shot in

Morse

. As John Madden, not aware of the personal relevance of the scene, described it in his obituary:

My most poignant memory of him is at the end of Julian Mitchell’s episode, ‘The Promised Land’, which we spent four months

shooting in New South Wales, when Morse travels to Australia in search of a supergrass. It all goes wrong and it is all Morse’s

fault. In the final scene he stands at the foot of the Sydney Opera House steps.

‘What are you going to do?’ he asks Lewis.

Lewis plans to meet his family. Morse wishes him well, looks after him as he goes and then turns to mount the endless steps,

carrying in every agonised step the loneliness and pain of mankind. Is this an exaggeration? For me it was great acting. Every

actor creates his part with the audience. John had built this character with all of us, we all knew him. We didn’t want him

to walk away.

7 April

Not besotted with Barcelona. Too noisy, too much traffic.

Hotel pretentious. But then I’m not in the right frame of

mind. Abs has summed it up in a poem, which I want her

to do at the memorial service if she can face it:

Last week we went to Barcelona.

A beautiful city; the kids had fun.

He really should have come too – I missed him.

Mum thought it would be a good thing too.

He had wanted to go for twenty years.

So last week we went to Barcelona.

So excited when he opened the card:

First class tickets and a suite at the Ritz.

He really should have come too – I missed him.

We held a simple funeral at home;

Sorted through his clothes and belongings

And last week we went to Barcelona.

When the cancer came back we’d changed the dates

Something to look forward to, the doctors had said.

He really should have come too – I missed him.

‘He would have liked this’ became our mantra.

Endless booze-soaked toasts, ‘Happy birthday, Dad’.

Last week we went to Barcelona.

He should have come too – I missed him.

In 1990 both

Morse

and

Home to Roost

were in the Top 10 of the ratings. John was at the height of his popularity but off screen he was fighting profound depression.

During our eighteen-month separation I wrote to him: ‘I and the girls will do almost anything to make you happy. You are deeply

loved and we long for you to discover how good life can be . . . it is terrible for me and the girls to watch you being so,

so sad. You feel lonely and persecuted but you only have to ring one of your daughters and they would be there. They daren’t

ring you, sadly.’

We were still living apart, incapable of communicating, when John chose his eight records to take on a desert island in

Desert

Island Discs

. They were all a coded message to me. One Easter at the start of our marriage, we were going to go to Handel’s

Messiah

at the Albert Hall. We couldn’t get in, so we rushed over to the Festival Hall where they were performing the Bach

St Matthew Passion

. I was not a great Bach fan then, saying, in my supreme ignorance, that he did not write nice tunes. I was horrified when

I discovered that the concert was five hours long with a supper break. It turned out to be an evening of revelation and pure

ecstasy. We were higher than any drug could send us. Another of his choices was me singing ‘Little Girls’ from

Annie

. The Sibelius was the music we had listened to in his car when on tour with

So What About Love

? The Schubert was one he had gone to a lot of trouble choosing as incidental music for a production of mine. The Elgar Cello

Concerto was a favourite of us both. One of Strauss’s

Four Last Songs

was sung by Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, who, he quite truthfully told Sue Lawley, he often joked was the only woman he would leave

me for. He was less truthful when, in parrying Sue’s questions about his drinking, he said he had stopped and found it as

easy as giving up sugar in his tea.

His denial of his problem should have sent out warning signals but the ploy was irresistible. All the reminders of why I loved

him and the things we had in common touched me. He was filming an episode of

Morse

in Verona and I rushed out there to join him. Then he came to Los Angeles with me where I was filming

Three Men and a Little Lady

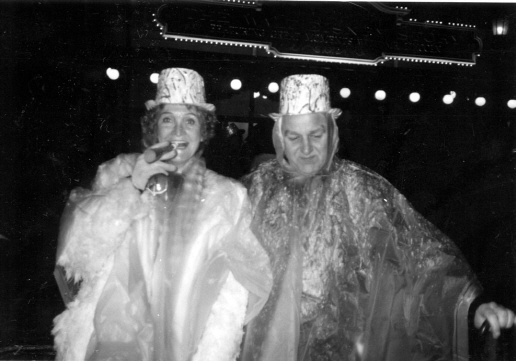

. We had a wonderful time, except on a visit to Disneyland, where it teemed with rain and Joanna persuaded us to wear absurd

plastic hats.

21 April

A day from hell. The BAFTAs. Terrified getting ready. The

indispensable Martyn propped up my face with make-up

and gave me a pep talk. Jo, Ellie and I gripped hands and

walked the red carpet.

Photographers and fans screamed, ‘Sheila, Sheila, this

way, this way.’ Jo was terrified I had to collect an award

for John. I was all right until they showed some clips of

him. It was the first time I’d watched him. Thank God I

had Dominique, the little girl from

Buried Treasure

with

me, so I had to pull myself together so as not to upset her.

Made a speech I think. Can’t remember what I said. Then

had to wait to see if I had won Best Actress for

Russian Bride

. It was Julie Walters. Bit disappointed because I’ll

never have such a good part again, and everyone was very

hopeful. But there you go. The little fat one with the white

hair got his. At the do afterwards colleagues were lovely. I

do love actors. They are thoroughly nice people. Such a

small community really. I mean proper actors not celebrities.

After all these years, between us John and I seem to

know everyone. They all seemed genuinely sad at his death.

Over the next five years John and I behaved like characters in a cartoon, ricocheting in and out of each other’s arms. It

became farcical. By the start of the nineties our two older girls had their own lives and loves; they were growing up, we

were becoming infantile. In 1993 Joanna went off to Paris for a year. She could not keep up with our on-off relationship.

Every time we got back together again we would buy a new home or do something to an existing house or garden. It was as if

we were trying to strengthen the marriage by improving the setting, instead of getting down to the root cause of our problems.

In 1991 we found a tumbledown stone house in a

hameau

in the Luberon in France. It was surrounded by a cherry orchard, vineyards and lavender fields. There were no English people

so we were blissfully anonymous. We sat in cafés and looked in shops instead of tearing around with our heads down to escape

attention. John visibly relaxed and only occasionally let out a faint, ‘Au secours moi, je want to reste ici.’

But we couldn’t stay in France all the time. Back in England and back at

Morse

, it all fell apart again. The house by the river in Chiswick became associated with miserable silences and fierce rows. OK.

Change it. How about a house in the country? In 1992 we acquired a Cotswold stone house by a stream with a field attached

in Luckington, which became known, rather optimistically, as Lucky. That didn’t work. So we bought a flat in Chiswick as well.

We re-created two gardens, redid a kitchen and two bathrooms. Each piece of property development marked a rupture and supposed

fresh start. It was absurd, and our girls got very angry with us. They could not understand or bear the pain we seemed to

be inflicting on each other. They came home less and less, saying it was like having an invalid in the house to tiptoe around

John’s erratic moods and my distraught reaction to them.

Madness seemed to be in the air in the nineties, it wasn’t just us. We were urged to be entrepreneurial, to look after ourselves

and our families and not rely on the state, although curiously Thatcher herself was quoted as saying that for her home was

somewhere to go to if you had nothing better to do. The increase of individual acts of violence was a distortion of the Me

Society. One man took it upon himself to kill gays and people from ethnic minorities with homemade nail bombs. Thomas Hamilton

shot dead sixteen children and a teacher in Dunblane in revenge for personal grievances. Another man did the same in the streets

of peaceful Hungerford. Some youths killed a black lad, Stephen Lawrence, and a later report concluded that not only were

they racist but the police showed institutional racism in the way they handled the case. In the US, a right-wing ex-soldier

killed over a hundred people with a bomb in front of a federal building in Oklahoma. Two youths shot thirteen schoolfriends

in Denver. A bomb exploded in one of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, though it was not given much coverage. There

were constant IRA atrocities, most notoriously in Omagh where twenty-nine people died, and in Manchester in 1996, when the

Exchange Theatre and a lot of the city centre were destroyed. A more positive event in the nineties was that thanks to Thatcher,

John Major and later Blair and Clinton, and some Irish politicians, the greatly improved situation in Ireland meant that terrorist

acts on the mainland became rare. Clinton also looked on as Arafat and Rabin shook hands over the Palestinian problem. In

1995 Rabin was killed at a peace rally and they were back to square one.

As the century drew to a close the atmosphere was tainted by disturbing murder cases. The squalor of the Wests’ sordid lives

led to savage butchery for which the suicide of Fred West and his brother seemed a fitting end. The whole nation was appalled

that two ten-year-old boys could kill the two-year-old James Bulger. With the murder of Sarah Payne, paedophilia became the

decade’s evil of choice to get worked up about. We were forced to peer into lives that horrified us. Hidden lives.

25 April

Recording

Bedtime

again. Everyone was wonderful but last

time I did it John was alive. Dreaded going home to empty

house. He would have welcomed me, ‘How did it go, pet?’,

cooked a meal, fussed over me. But the house was empty,

I had no food in and no one to dissect the day with. I

actually would rather be dead than live like this. I can’t do

solitude.

Keep thinking of what I was doing this time last year

before this calamity. Today we were in France having a

picnic up in the mountains of Silverque with Liz and David.

We lay in the sun, ate, laughed and hadn’t a care in the

world.

In my childhood little was known about what went on behind the gates of Buckingham Palace. The Duke of Windsor’s affair with

Wallis Simpson was kept secret from the hoi polloi. Now the Queen’s business was pried into by the scandal-obsessed press.

She declared 1992 her

annus horribilis

. Windsor Castle had a major fire and all her sons and her daughter had relationship problems. Nothing more vividly illustrates

the changes in society than the blank bewilderment on this good woman’s face. Everything she had been taught to believe in

was disintegrating. My world too seemed to be crumbling. In 1992 I did a TV series aptly named

Gone to Seed

in which I played opposite Peter Cook. I had known him during and just after his university days. He wrote much of the material

of the revue that I did with Kenneth Williams. He was at that time a hilariously funny, extremely beautiful young man. Now

he was a shambling, sweating wreck. Alcohol had destroyed him. He died three years later, aged fifty-seven.

It had begun to seep into our thick consciousness that our difficulties would never be sorted without confronting John’s drinking

and my attitude to it, which in his opinion was more of a problem. John made several attempts to stop but always fell off

the wagon as he tried to pull off the impossible feat of doing it on his own. He filled his mind with work, which was not,

as yet, affected by his drinking. But the situation was not helped by him doing two projects that were not a great success.

Stanley and the Women

, adapted from the book by Kingsley Amis, could not hide its misogynist theme. John’s attempt to transform his appearance

for the part, resulting in orange hair, did not improve it either.