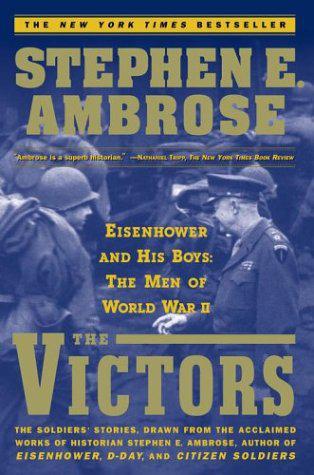

The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys : The Men of World War II

Read The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys : The Men of World War II Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #General, #History, #World War, #1939-1945, #United States, #Soldiers, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Campaigns, #Western Front, #History: American, #United States - General

Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II

THE VICTORS

Stephen E. Ambrose

Portions of this work were previously published in Eisenhower, PegasusBridge, Band of Brothers, D-Day,and Citizen Soldiers.

FOR ELIZABETH STEIN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

1 - Preparation

2 - Getting Started

3 - Planning and Training for Overlord

4 - “OK, Let’s Go”

5 - The Opening Hours of D-Day

6 - UtahBeach

7 - OmahaBeach

8 - Pointe-du-Hoc

9 - The British and CanadianBeaches

10 - The End of the Day

11 - Hedgerows

12 - Breakout and Pursuit

13 - At the German Border

14 - Metz, Aachen, and the Hurtgen

15 - The Battle of the Bulge

16 - Night on the Line

17 - The Rhineland Battles

18 - Overrunning Germany

19 - The GIs

Sources

Bibliography

Copyright

Also by Stephen E. Ambrose

Introduction

MY EXPERIENCES with the military have been as an observer. The only time I wore a uniform was in naval ROTC as a freshman at the University of Wisconsin, and in army ROTC as a sophomore. I was in second grade when the United States entered World War II, in sixth grade when the war ended. When I graduated from high school in 1953, I expected to go into the army, but within a month the Korean War ended and I went to college instead. Upon graduation in 1957, I went straight to graduate school. By the time America was again at war, in 1964, I was twenty-eight years old and the father of five children. So I never served. But I have admired and respected the men who did fight since my childhood. When I was in grade school World War II dominated my life. My father was a navy doctor in the Pacific. My mother worked in a pea cannery beside German POWs (Afrika Korps troops captured in Tunisia in May 1943). Along with my brothers-Harry, two years older, and Bill, two years younger-I went to the movies three times a week (ten cents six nights a week, twenty-five cents on Saturday night), not to see the films, which were generally real clinkers, but to see the newsreels, which were almost exclusively about the fighting in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific. We played at war constantly: “Japs” vs. marines, GIs vs. “Krauts.”

In high school I got hooked on Napoleon. I read various biographies and studied his campaigns. As a seventeen-year-old freshman in naval ROTC, I took a course on naval history, starting with the Greeks and ending with World War II (in one semester!). My instructor had been a submarine skipper in the Pacific and we all worshiped him. More important, he was a gifted teacher who loved the navy and history. Although I was a premed student with plans to take up my father’s practice in Whitewater, Wisconsin, I found the history course to be far more interesting than chemistry or physics. But in the second semester of naval ROTC, the required course was gunnery. Although I was an avid hunter and thoroughly familiar with shotguns and rifles, the workings of the five-inch cannon baffled me, so in my sophomore year I switched to army ROTC. Also that year, I took a course entitled “Representative Americans” taught by Professor William B. Hesseltine. In his first lecture he announced that in this course we would not be writing term papers that summarized the conclusions of three or four books; instead, we would be doing original research on nineteenth-century Wisconsin politicians, professional and business leaders, for the purpose of putting together a dictionary of Wisconsin biography that would be deposited in the state historical society. We would, Hesseltine told us, be contributing to the world’s knowledge.

The words caught me up. I had never imagined I could do such a thing as contribute to the world’s knowledge. Forty-five years later, the phrase continues to resonate with me. It changed my life. At the conclusion of the lecture-on General Washington-I went up to him and asked how I could do what he did for a living. He laughed and said to stick around, he would show me. I went straight to the registrar’s office and changed my major from premed to history. I have been at it ever since.

As for this book, Alice Mayhew made me do it. Two years ago I sent in to her the manuscript of a book she eventually titledCitizen Soldiers (she picks all my titles, including the one for this book). That was the eleventh manuscript I had sent her-three volumes on Eisenhower, three volumes on Nixon, one on a British airborne company in World War II, one on an American airborne company in that war, one on D-Day, and one on Meriwether Lewis. All but the Nixon volumes and the Lewis book were on war, and there was plenty of war in the second and third Nixon volumes-and Lewis led a military expedition. So when I put the manuscript of what becameCitizen Soldiers in the mail, I promised my wife, Moira, “I ain’t going to study war no more.” I had seen enough destruction, enough blood, enough high explosives. To remove temptation, I gave my library of World War II books to the Eisenhower Center at the University of New Orleans. Like the Civil War veterans after Appomattox, like the GIs after the German and Japanese surrenders, I wanted to build. Alice accepted my decision and told me to write a book on the building of the first transcontinental railroad. I loved the idea and put in a year of research. Then Alice called and said I should do a book on Ike and the GIs, drawing on my previous writings to put together a coherent narrative. She said it would be the easiest book I’d ever write. That didn’t turn out to be so, as there was lots of hard work involved. But it has been the most fun. The challenge of writing a history of the Supreme Commander and the junior officers, NCOs, and enlisted men carrying out his orders-generally ignoring the ranks in between-has given me a new appreciation of both.

The older I get, the more of his successors as generals and presidents I see, the more I appreciate General and President Eisenhower’s leadership. And the more I realize that the key to his success as a leader of men was his insistence on teamwork and his devotion to democracy.

General Eisenhower liked to speak of the fury of an aroused democracy. It was in Normandy on June 6, 1944, and in the campaign that followed, that the Western democracies made their fury manifest. The success of this great and noble undertaking was a triumph of democracy over totalitarianism. President Eisenhower said he wanted democracy to survive for all ages to come. So do I. It is my fondest hope that this book, which in its essence is a love song to democracy, will make a small contribution to that great goal.

1 - Preparation

AT THE BEGINNING of World War II, in September 1939, the Western democracies were woefully unprepared for the challenge the totalitarians hurled at them. The British army was small and sad, the French army was large but inefficient and demoralized from top to bottom, while the American army numbered only 160,000 officers and men, which meant it ranked sixteenth in the world, right behind Romania. The totalitarian armies of Imperial Japan, the Soviet Union, and Nazi Germany, meanwhile, were larger and better prepared than their foes. As a consequence, between the early fall of 1939 and the late fall of 1941, the Japanese in China, Indochina, at Pearl Harbor, and in the Philippines and Malaya; the Red Army in Poland and the Baltic countries; the Germans in Poland, Norway, Belgium, Holland, and France, won great victories. The only bright spots for the democracies were the British victory in the Battle of Britain in the summer and fall of 1940 (but that was a defensive victory only) and Adolf Hitler’s decision to attack his ally Joseph Stalin in the spring of 1941. Because of the last two events, the apparently certain totalitarian victory of May 1940 was now in question. Perhaps the democracies would survive, perhaps even prevail and emerge as the victors. That depended on many things, but most of all on the abilities of the British and Americans to put together armies that could challenge the Japanese and German armies in open combat. That required producing leaders and men. How that was done is the central theme of this book. We begin with Dwight David Eisenhower, the man who became the Supreme Commander of the British and American armies that formed the Allied Expeditionary Force. His personality dominated the AEF. He was the man who made the critical decisions. In the vast bureaucracy that came to characterize the high command of the AEF, he was the single person who could make judgments and issue orders. He had many high-powered subordinates, most famously Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery and Gen. George S. Patton, but from the time of his appointment as Supreme Commander to the end of the war, he was the one who ran the show. For that reason, he gets top billing here.

Eisenhower was a West Point graduate (1915) and professional soldier. When the war broke out, he was a lieutenant colonel serving on the staff of Gen. Douglas MacArthur in the Philippines. By mid-1941 he had become a brigadier general and chief of staff at the Third Army, stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He was there that December 7; on December 12 he got a call from the War Department ordering him to proceed immediately to Washington for a new assignment. What he did over the next few weeks, and what happened to him, illustrate how ill-prepared the American army was for war, and how fortunate it was to have Eisenhower in its ranks.

On Sunday morning, December 14, Eisenhower arrived at Union Station in Washington. He went immediately to the War Department offices in the Munitions Building on Constitution Avenue (the Pentagon was then under construction) for his initial conference with the Chief of Staff, Gen. George C. Marshall. After a brief, formal greeting Marshall quickly outlined the situation in the Pacific-the ships lost at Pearl Harbor, the planes lost at Clark Field outside Manila, the size and strength of Japanese attacks elsewhere, troop strength in the Philippines, reinforcement possibilities, intelligence estimates, the capabilities of America’s Dutch and British allies in Asia, and other details. Then Marshall leaned forward across his desk, fixed his eyes on Eisenhower’s, and demanded, “What should be our general line of action?” Eisenhower was startled. He had just arrived, knew little more than what he had read in the newspapers and what Marshall had just told him, was not up to date on the war plans for the Pacific, and had no staff to help him prepare an answer. After a second or two of hesitation Eisenhower requested, “Give me a few hours.”

“All right,” Marshall replied. He had dozens of problems to deal with that afternoon, hundreds in the days to follow. He needed help and he needed to know immediately which of his officers could give it to him. He had heard great things about Eisenhower from men whose judgment he trusted, but he needed to see for himself how Eisenhower operated under the pressures of war. His question was the first test.

Eisenhower went to a desk that had been assigned to him in the War Plans Division (WPD) of the General Staff. Sticking a sheet of yellow tissue paper into his typewriter, he tapped out with one finger, “Steps to Be Taken,” then sat back and started thinking. He knew that the Philippines could not be saved, that the better part of military wisdom would be to retreat to Australia, there to build a base for the counteroffensive. But the honor of the army was at stake, and the prestige of the United States in the Far East, and these political factors outweighed the purely military considerations. An effort had to be made. Eisenhower’s first recommendation was to build a base in Australia from which attempts could be made to reinforce the Philippines. “Speed is essential,” he noted. He urged that shipment of planes, pilots, ammunition, and other equipment be started from the West Coast and Hawaii to Australia immediately.

It was already dusk when Eisenhower returned to Marshall’s office. As he handed over his written recommendation, he said he realized that it would be impossible to get reinforcements to the Philippines in time to save the islands from the Japanese. Still, he added, the United States had to do everything it could to bolster MacArthur’s forces because “the people of China, of the Philippines, of the Dutch East Indies will be watching us. They may excuse failure but they will not excuse abandonment.” He urged the advantages of Australia as a base of operations-English-speaking, a strong ally, modern port facilities, beyond the range of the Japanese offensive-and advised Marshall to begin a program of expanding the facilities there and to secure the line of communications from the West Coast to Hawaii and then on to New Zealand and Australia. “In this,” Eisenhower said, “. . . we dare not fail. We must take great risks and spend any amount of money required.”

Marshall studied Eisenhower for a minute, then said softly, “I agree with you. Do your best to save them.” He thereupon placed Eisenhower in charge of the Philippines and Far Eastern Section of the War Plans Division. Then Marshall leaned forward-Eisenhower recalled years later that he had “an eye that seemed to me awfully cold”-and declared, “Eisenhower, the Department is filled with able men who analyze their problems well but feel compelled always to bring them to me for final solution. I must have assistants who will solve their own problems and tell me later what they have done.” Over the next two months Eisenhower labored to save the Philippines. His efforts were worse than fruitless, as MacArthur came to lump Eisenhower together with Marshall and President Franklin D. Roosevelt as the men responsible for the debacle on the islands. But throughout the period, and in the months that followed, Eisenhower impressed Marshall deeply, so deeply that Marshall came to agree with MacArthur’s earlier judgment that Eisenhower was the best officer in the army.