The Village Against the World (14 page)

Read The Village Against the World Online

Authors: Dan Hancox

A lot of her friends left school when they were fifteen, Emma explained. The authorities didn’t really mind, because they knew there was work available, and they needed people to do it. ‘The government just said, “Okay, leave school, go!” So now in the south you have a lot of young unemployed people with no qualifications, but they have a house and they have a family and they have a loan, and they need to pay for everything – and they can’t go back to school, because they have responsibilities. What are you going to do in that situation?’

There is little else to do but come out into the plazas, in fact – either to idle, or to organise. Access to the monthly unemployment benefit is being limited, she said, with new applicants blocked by bureaucracy – because the

government’s austerity programme simply can’t afford to give it to everyone who is unemployed; there are just too many of them.

Back in Marinaleda we were invited to visit one of the

casitas

, the self-built houses, belonging to a family with two grown-up children facing up to the realities of the crisis-era job market. The invite had come via Javi’s twenty-seven-year-old friend Ezequiel, who I’d met once in London, when he was a diffident young man lost in the big city, mute from lack of English, slightly perplexed at my enthusiasm for his obscure little

pueblo

. His family story is a common one – like Cristina’s parents, his grandparents migrated north in search of work in the 1950s. His father was born in Barcelona but went back to his roots, to Marinaleda, to find work when the struggle for land began, and soon met Ezequiel’s mother, from Estepa. ‘A lot of people never came back to the south,’ Javi explained.

Ezequiel had returned to his parents’ house because he had a couple of days off from his job working in a Seville hotel reception, and greeted us warmly – cheeky smiles swim near the surface of the Andalusian gene pool. The house was lovely; modest but big enough, clean but lived-in. Each of the 350

casitas

built under Sánchez Gordillo’s leadership consists of ninety square meters for construction and 100 square meters for a patio or garden, and normally incorporates three bedrooms, a bathroom, living room, kitchen and courtyard. The living room was

dominated by a towering bookcase and a large cage of chirruping birds. ‘Say “Gordillo”!’ Javi instructed a parrot, pointing a finger at it mock sternly. The parrot looked at him impassively and puffed its chest out. ‘Say “communism”!’ The bird refused.

Ezequiel is one of many young

marinaleños

torn between utopia and the wider world. He wanted to do something more exciting than farming, he explained, whatever the benefits of the co-operative might be. He spent most of the week working in the hotel in Seville, improving his English, renting a small room in a flat there, but even so hadn’t quite cut the apron-strings to utopia: he was still coming back to stay at his parents’ house most weeks and was on the waiting list to build a

casita

of his own in Marinaleda, in spite of his wanderlust. A fifteen-euro-a-month ‘mortgage’ for a brand-new house in his

pueblo

, especially in the context of the Spanish housing crisis, would be pretty hard to argue with.

Did you like it, growing up here? I asked him. ‘Sure. But if you don’t want to work in the fields, what do you do?’ What indeed. You probably have to leave for the big city or the coast. Do people here grow up as communists? I wondered. He seemed unsure of what to say. ‘Many people become communists, because they want to work, or they want to have a house, but not because they

are

communist. They don’t sit at home reading Karl Marx.’

In a way, Ezequiel was no different than any Spaniard of his age – more enticed by the possibilities of gallivanting

and adventure than by Sánchez Gordillo’s earnest poems about struggle. His parents came back from Catalunya to join the revolution, he acknowledged. ‘Ah, but this generation, they don’t care about communism,’ interrupted Javi, mocking Ezequiel for his ideological heresy. There was some truth to Javi’s jibe, and I heard it said more than once in the village, and in the surrounding

pueblos

, that those who inherited utopia may not treat it with the same reverence as those who struggled to create it.

And yet, even with Ezequiel, it felt like a certain level of solidarity had been unconsciously embedded: despite his middling English, he wanted to practice, and told a lucid English-language version of the history of the land seizures that had happened before he was born. The Duke of Infantado, he said, was ‘just walking around with a horse, while people starved in Marinaleda’. And then he reeled off the word ‘expropriated’ without a second thought.

Most English people don’t know the word ‘expropriated’, I told him.

5

Bread and Roses

With the exception of the ferocious heat of high summer, Marinaleda feels at its most utopian in the afternoon.

La tarde

starts not at noon, but when work starts winding down and lunch and siesta time commence, between 2 and 4 pm. The village’s few shops and workshops close, workers drift back from the fields and the factory, the pensioners finish their games of cards, and parents stand outside the primary school gates, chatting idly as the kids run in circles around their legs.

Some stop off for a drink on their way home and sip small glasses of beer called

cañitas

(normally about a third of a pint) under the sun-gazebo in front of Bar Gervasio and at the tables outside Bar Sur. Lunch, which never starts before 3 pm, is normally a long-drawn-out affair involving several courses, with loaves of bread broken up into big hunks sitting on the table next to platters of grilled chicken or pork, rich stews of lentils and beans, fanned triangles of manchego and bowls of pale, watery lettuce, tossed with tuna and sweetcorn.

Home is where the stomach is, but the social centre of the Spanish

pueblo

, as Julian Pitt-Rivers observed in his book

The People of the Sierra

, is outdoors, in the streets themselves. During

la tarde

, the broad, tree-lined promenade that runs next to the Avenida de la Libertad, connecting Marinaleda to nearby Matarredonda, is teeming with activity. Gaggles of middle-aged women walk four abreast, men just turning grey jog in pairs, and teenage boys on bikes do that half-standing, half-cycling soft-pedal thing that only teenage boys can pull off, while the girls walk behind them, laughing. The older youths are kitted out as cool young sportsmen, and pose with their lightweight motorbikes, or lean on car doors showing off their tracksuits, like aspiring alpha males everywhere.

After lunch and a short siesta, the heat of the day cools, and the performance is repeated. The pensioners rest their walking sticks against the metal green benches, stocky men stroll two by two in their berets, serious trousers and olive-coloured cardigans, always nattering away, the birds in the surrounding orange trees by now engaged in deep debate too. Outside the

casitas

kids walk their dogs and chase their footballs, and a group of roller-skating tweens flies down the Avenida and into the village park, past the outdoor gym, which is populated by grown-ups doing their work-outs and children using it as a climbing frame. The younger children sit on their mothers’ laps on the benches, eating crisps. If you do a circuit of the village, by the time you return half an hour

later the congregations around each bench have rearranged slightly, but the principle remains.

Between the Ayuntamiento and Matarredonda a lush green field spreads motionless in the afternoon sunshine, only occasionally disturbed by the two white horses grazing in it. When the sun finally sets, it does so in a blaze of pink over El Rubio to the west, casting an irresistible peach glow over the whitewashed walls of the town, with Estepa sitting prettily on the balcony of the mountains to the south. When there is more than, say, 50 per cent cloud coverage, which there very rarely is, dusk is a moodier affair of purplish, deep-sea blues, but no less picturesque.

‘We have every reason to keep fighting’, proclaims a slightly torn Sánchez Gordillo election poster still clinging to the wall of the

parque natural

. It’s not just their work, but their lifestyle that they’re fighting to keep – and in almost every instance, it’s one that they created from the space they won for themselves: not just via the economically empowering struggle for land, but by deliberately building the infrastructure for a cultural and social life far out of proportion with their size.

The Gordillistas never miss an opportunity to remind people of the connection between the

marinaleño

quality of life and

la lucha

. ‘You truly believe that without struggle we could achieve all this?’ demanded the central spread of the 2011 election manifesto brochure, illustrating such achievements with countless pictures of high days and holidays, community activities, sports teams and facilities,

and organised fun for children, pensioners and everyone in between.

When the streets are your social centre, it’s important to keep them clean. All the house facades are immaculate, the majority of them gleaming white, with only a few rogues in yellow or orange, or covered in beautiful Moorish mosaic tiles. On a morning stroll around the village you’ll most likely encounter a few women outside their front doors, sweeping dust and twigs from the pavements. One matriarch beats the front of El Sur with a kind of cat-o’-nine-tails to get the dust out. It still hangs in the air a little, augmenting the hazy sunshine with an extra layer of fuzz. It’s a constant struggle, when the motorbikes haring down Avenida de la Libertad are kicking up their own oily smoke too, and the lorries are churning up the dust.

On Sundays, on Calle de Federico García Lorca, one household literally airs its laundry in public, hanging wet linen on a line between the orange trees on the pavement. Nobody minds. Public space is negotiated space, and if someone has a problem with a fellow neighbour’s use of it, they will mention it directly. It’s too hot in this part of the world to waste time on working yourself up with passive-aggressive grumbling.

If you’re not taking the most important meal of the day at home, there’s a small range of modest but tremendously cheap tapas dishes in the bars of the village, usually costing one euro each, same as the beers, the glasses of wine and the coffees. And just on the very edge of the village, near

the road sign which indicates you are entering Marinaleda, is La Bodega – a proper, spacious family restaurant for passing traffic and locals alike. By 3.30 on weekday lunch-times it’s pretty much full, with fifteen or so cars, lorries and tractors parked outside.

Extended families, work associates and groups of retirees eat there often in large groups of more than ten, drinking decent reds and helping themselves from great communal clay pots of chicken and potatoes. Competing with the flamenco-pop on the stereo is a whirring ceiling fan and

The Simpsons

, dubbed, on a TV in a high corner. There’s an open fire, an old-fashioned wood-burning heater, a giant, human-being-sized amphora turned into a plant pot, open shelves messily stacked with wine bottles, and hams hanging behind the bar. The atmosphere reflects the gloriously unhurried Andalusian ethic:

no hay bulla

, there’s no fuss. Even the

sopa de mariscos

, seafood broth, off the daily

menú del día

takes over thirty minutes to arrive; but if you’ve got half-broken, briney olives from the local fields, a good book and a sparkling

cañita

, there really is no fuss.

You can eat a long, langorous lunch, but people also head there in the evenings for less formal tapas plates of rich

rabo de toro

, ox tail,

secreto

, a gloriously moist, fat-marbled cut of pork, and

flamenquín

, the peculiar Andalusian hybrid of a scotch egg and a sausage roll. Eating there with Javi and his mates on a Friday night, they taught me the kind of key contemporary Spanish phrases you don’t learn in a language

class. Phrases such as

dinero negro

, black money, and that Rajoy’s government had recently offered the nation’s corrupt businesspeople an

amnistía fiscal

. This meant that they would clean their dirty money, no questions asked, no charges pressed, only provided they brought it back to Spain and paid 10 per cent tax on it. And then there was gossip about the various senior politicians embroiled in various corruption scandals. I struggled to keep up with which one was which: there were simply that many cases in the news at any one time.

After some light dinner like this, at around 9 or 10 pm, for the younger adults (and many of the older ones) weekend nights mean more drinks, gently sliding along from bar to bar, either in the village or a neighbouring

pueblo

, and eventually some dancing.

In terms of decibel levels Marinaleda is generally a quiet village, but when they celebrate, they do so in a manner which is once again far out of proportion to their size. The major annual festivals – most of them Catholic in origin, now stripped of all religious rituals and icons – draw in thousands of outside visitors, from neighbouring villages and beyond: chiefly the pre-Lenten

carnaval

blow-out, the week-long July

feria

, and Holy Week recast as

semana cultural

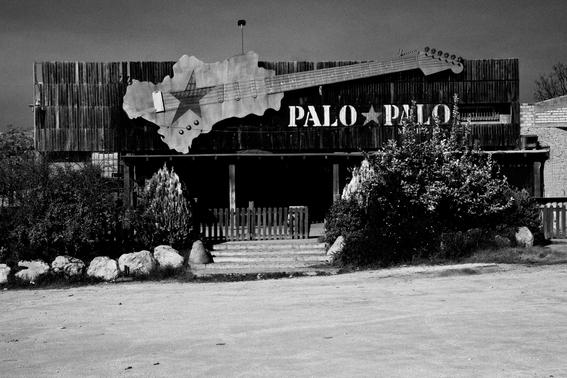

. In addition there are the famous spring and summer rock concerts, either in Palo Palo or outdoors in the

feria

grounds, which frequently see the village double in size.