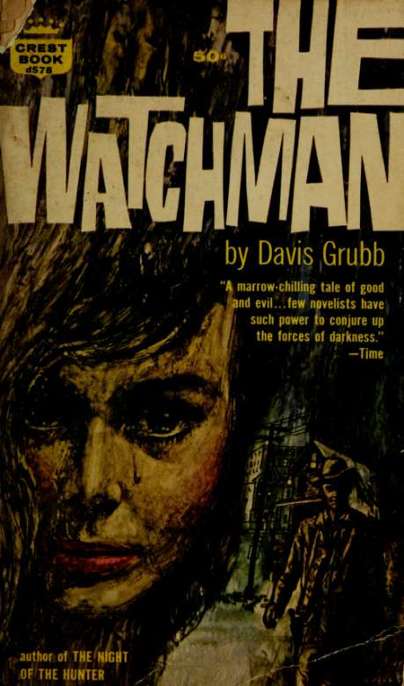

The Watchman

Authors: Davis Grubb

one

Stripped down to nothing but a suit of long under-wear and gray cotton socks the tough bulk of the big man on the Httle hotel bed seemed bigger than if it had been dressed. His legs stuck out between the brass bars of the bed's foot. His stuffed, tight shoulders extended far out over each side of the narrow, horsehair mattress. He had lain there nearly motionless for four hours. Now it was early evening—almost time for the killing. The single window of the room was open but the blind was pulled to the sill. So that the air was cold. Yet, despite that, the leathery face of the big man was flushed with the fever of savage speculations: his forehead beaded and trickling with sweat. And each quarter-hour when the wall clock struck its announcement far down in the lobby of the country hotel the gray eyes of the big man glazed, his clenched mouth paled, and the big shape of him shuddered so that, for a moment, the sagging bedsprings sang and cried like a cage of rabid ferrets. Every article in the room had been rearranged to fresh placements of personal and astonishing eccentricity. Across the bureau mirror had been draped a threadbare bath towel upon which dimly could be read MOUND HOTEL. On the dresser top, beside the cracked leather of a broken, bulging Bible lay the big man's blue revolver. The keyhole of the hallway door, locked from the outside, was stuffed with newspaper. Yet, despite that precaution a heavy marble-topped washstand was jammed beneath the china knob. On the dusty rug beside the bed an ancient, broken table-radio hummed and crackled. Its sound filled the room with thin disturbance: a deranged and insect murmur. And yet that sound and the murmur through the open window of the small town night and the laughter of men's voices down in the lobby did not keep

Luther Alt from hearing the four soft knocks against the door. Yes, he thought, stiffening and closing his eyes a moment. Yes, time now, he thought. Time to get up and dress and strap on the gun and go: time for the kilHng. He opened his eyes, stiffened, then sprang out of bed, crossed the room, stood by the door in a half-crouch searching the walnut panels. He whispered a challenge of query, heard the muffled, unintelligible reply of a man's voice, waited, then heard presently again the light knocks. And thinking: It might be him. But then again it might not. It might be old Dobey sent up to rouse me. But then again it might be someone else.

Luther Alt swiftly crossed to the bureau, caught up the thirty-eight revolver, broke it open, saw its loaded chambers. He stood an instant staring at his big gun, somehow crippled now in his hand. Yes, he thought, it might be someone else. He inverted the gun, shook it hard, watched the five brass cartridges tumble out into the palm of his other hand. The man outside rapped more sharply now.

Directly! called Luther Alt and dropped the bullets into the pocket of his jacket on the chair by the washstand. He looked at the empty revolver with a grunt of relief, a notion of safety. Then he went to the door again, put his ear to the panel. He moved the washstand away from the knob and waited for the knock again.

Is that you, Dobey? he whispered, but the one beyond the oak did not hear him and rapped again, sharply now.

Who is it? cried Luther Alt.

It's me, Sheriff. It's the night clerk.

Who?

The night clerk! said the voice sharply at the crack of the door. Dobey the night clerk. You said for me to come and unlock you when it's time. Well it's come time.

Unlock the door, said Luther Alt wearily. He went back and fetched out the cartridges from his jacket, went to the dresser, broke open the revolver again, slowly loading it while he listened indifferently to the clatter and scratch of the night clerk's housekey, the opening of the door. The night clerk thrust his birdlike head inside for an instant to be certain Luther was awake and up. Luther listened, without turning.

You all right, Sheriff?

I'm all right, Dobey. Thank you, Dobey, said Luther, and listened to the whisper of the night clerk's carpet slip-

pers fading away again down the hallway. He dressed swiftly now, strapping on the gunbelt, sliding his big shoulders into the jacket. For an instant before he left the room he hfted his head, murmuring something, raising his eyes slowly to the dim light of the room's ceiling globe: a frosted, mindless moon shedding the illumination of soiled twilight upon the squaUd room's sixty years of drummers' mercantile dreaming, the insomniac toss of transients drunk or half-mad with loneliness, the furtive and chronic embrace of lovers by the hour. The Sheriff's anguished eyes searched senselessly for that instant among the blurred, scattered pattern of dead moths and flies which calicoed the dull hght globe's interior: dried-up hieroglyphics of long-vanished simi-mer nights. Perhaps he imagined something was to be read there; maybe an answer to his torment. And for that moment his mouth murmuring softly, uninteUigibly, spoke to it or to himself or to the God beyond this spurious moon and thought to himself: How many more years? How many more towns? How long can a man keep running from it? Then he stiffened himself, passed through the open door, shut it behind him and moved down the hallway toward the stairway to the lobby, toward the men who sat there waiting to watch him pass, toward the street of the silent river night. And, of course, toward the killing.

On the water-green wall of the hotel lobby the hands of Peace the Undertaker's banjo clock stood at quarter past eight. The three men sat submerged in the couch and two chairs of bursted black leather and watched the river fog gather in the street beyond the long glass window. Dobey the night clerk fussed behind his front desk. The men had talked little in the hour since the woman had come slowly down the staircase and taken up her position on the straight-backed chair to the darkened dining-room door. They chewed and smoked and spat, listening to the growl of good dinners beneath their vests, watching the coming of the fog upon the long glass. An hour before—Uke this woman of the man who must die—it was not there. Since sundown the men had sat chatting in the lobby of the death that was to be done at nine. And then, hke the fog, the woman came.

It seemed to Mister Jibbons, the horse trader, that the woman was there to deprive them of something rightfully theirs; that she had come to spoil an occasion. And so it was from anger more than through any delicacy toward

the woman's feelings that he said the least of any, smoking and spitting and pondering the fog; avoiding the other men's eyes with the ritual diffidence of males in public toilets. The woman sat straight, hands folded upon her lap. Beneath her straight, streaked brown hair, knotted low on her neck, a hillwoman's face suggested that it had been pretty until the battering of long and humdrum mischances had convinced it that prettiness was not useful: a face that seemed not so much to have gone old as to have gone out, and one which somehow would have best grown ugly rather than having kept among its features of a faint, pinched prettiness the eroded traces of a girlishness long since become irrelevant. In that strained hour her gray eyes made their unending circuit: watch the backs of the men for a spell, then to the black telephone by the night clerk's gartered sleeve, then back to the hands of Peace the Undertaker's clock. Her gaze returned always to the neck of Jib-bons, the horse trader. In the deep crease of that fat nape between shaggy hairline and soiled collar Jibbons seemed to possess a second, lipless mouth. And it seemed to the woman in her racing fancies that this mouth might suddenly open and make a pronouncement of thunderclapping and unearthly reprieve. It was in the small curve of her own mouth that she showed how strongly she sensed her antagonists. But her eyes quietly declared that this place was where she belonged, this closest permissible place to her man on his night to die.

At the sound of the Sheriff's boot heels on the stairs the horse trader seemed roused from his glum trance.

Evenin', Luther, he declared loudly when the Sheriff was midway across the lobby. Luther turned briefly, glanced at Jibbons and the men beside him.

Good evening, gentlemen, he said.

He looked slowly to the face of the woman on the chair by the dining-room door. He seemed on the point of saying something until suddenly it seemed to occur to him that there was nothing to be said. He removed his hat, bowed his grizzled head and moved quickly on to the threshold, hurried into the night, closing the door softly behind him. The men listened to Luther Alt's boots ringing up the brick pavements, the sound diminishing at last in the fog.

By God, now there's a man, said Jibbons, the horse trader. A body sleeps better of a night hearing them boots making their rounds of the town. A man. Not much orneriness

can happen in a town with a man Hke Luther Alt out yonder sentrying the night.

Jibbons' tongue seemed suddenly freed by Luther's appearance; his eyes glistened, his face flushed, his gold teeth worked the stogie back and forth. He turned suddenly to the dour, dozing figure at his right.

Matthew Hood, how long you been retired now?

Hood touched a forefinger to his nose and gave the brief, modest cough of a pubhc speaker taken unawares.

It will be four years, three months and twelve days tomorrow, Mister Jibbons, he said.

Hood raised his fingers, touched their tips together, stared into his thumbnails. The hands of Matthew Hood were instruments of such fragile and curious beauty that it was impossible to imagine them belonging to the rest of him. Gloved in the firm and slender flesh of youth, with nails that were the long, immaculate ovals of a girl, these hands; those fine wrists, blue-veined and yet steel-strong, jutted from the seedy, frayed sleeves of an unmatching, hand-me-down jacket of bile-colored worsted which was mottled with stains of lunchroom stew, spilled whiskey, slobber, and perhaps, indelibly, with the dye of splashed horrors unremem-bered even in the mind of Matthew Hood himself. Within the coat his torso and shoulders mushroomed up into a bulge of sinew, gristle and bone which stuffed his coat so tightly that in order not to split the seams he moved generally with a stiff and thrifty caution which gave his movements an air of shoddy elegance, as if he were consul for all destitution. Hood lived alone in a room on the second floor of the hotel. He spent most of his evenings brooding in the black couch before the lobby window and traveling men often saw those hands, those astonishing hands, and were aware that he was exceptionally proud and careful of them, for there was always about him the faint odor of glycerine and rose water. Yet strangers seldom guessed what his trade had been, knowing only that, whatever it was, he was retired from it now, and something about those incongruous, brutal shapes of his body, the sleeves into which those elegant wrists disappeared, something of a nostalgic and affronted reserve about his bloodshot and unlaughing eyes kept anyone from ever asking Matthew Hood what once he had been. Tonight, however, even before the horse trader had spoken to him. Hood seemed uncommonly animate: the hulk of him immobile in its pinched, mean clothing but

the hands moving more than usual; not fidgeting restively but mobile with a subtle and manual liveliness as if they, more than the mind that moved them, remembered the old, fine days before they had been ordered idle.

Things, said the horse trader solicitously. Tilings aren't what they used to be up there, Matthew. There's more fuss now—more confusion when it comes to getting a thing like this done and over with.

Hood grunted and stared bitterly into the mists beyond the glass.

It used to get done quietly, the horse trader went on. And the kin never come to Adena to sit in public and shame themselves on the night when it was to be done. Not once in all those years, eh, Matthew? Leastways not that I mind of. No. They would wait—like decent Christians— and most of the kin was that—wait till the morning to come and claim the remains.

Jibbons scowled, took his stogie from his teeth, glared at the cold ash and fumbled in his vest for a kitchen match. While in his mind he fingered for a tinder of words, moving words, since nothing he had yet said to Matthew Hood had evoked more than one terse answer and that solitary grunt, and a slow caressing of those now useless hands, one against the other. Jibbons considered what words might unloose the floodgates of happy memories in that disenchanted heart. As things stood now he was uncomfortably suspicious that Hood wanted to hear about that night's killing as little as did the woman.

Progress, I reckon, he remarked with a scintillating intuition. Progress just says we have to change our way of doing things.

Hood's beautiful hands slowly clenched into fists, slowly unclenched again and lay lovely on his greasy cotton knees.

And they say, Jibbons went on swiftly, that it don't hurt as much. It's quicker. That's what Uncle Doc Snedeker claims and Godalmighty knows how many men he's watched go down.

Any hearsay, said Matthew Hood suddenly, that some damned fool assumes he heard said from somebody that a worse damned fool would know couldn't be heard to say anything—and I mean, namely, someone who is dead—is just the sort of damned fool nonsense that I would count on hearing from that old fool O. T. Snedeker M.D. I dropped the trap on forty-two men up yonder at the Pen

in my twenty years of service and I never heard one of them yet to tell me whether it hurt him none or not. Judging by the faces of them when we got the bag off it went easier with some than it done with others. Some folks' necks is just more naturally obliging than others is my opinion. Some folks goes into the chamber with entirely the wrong frame of mind—I mean they're all tensed up and braced and rebellious—and it's my judgment that they're the ones that don't get the clean, quick snap that get it over with quick. A man gets out of hanging just what he puts into it, as I told a nigger from Boone County one night and, by God, he smiled at me and when he went through the floor he was humming a gospel hymn just as relaxed as could be. Whenever I done my job I done it in a journeyman way—clean and artistic—but I could just do so much to make it easy—the rest was up to them. It takes two to square-dance, Trader, and that's a God known fact.