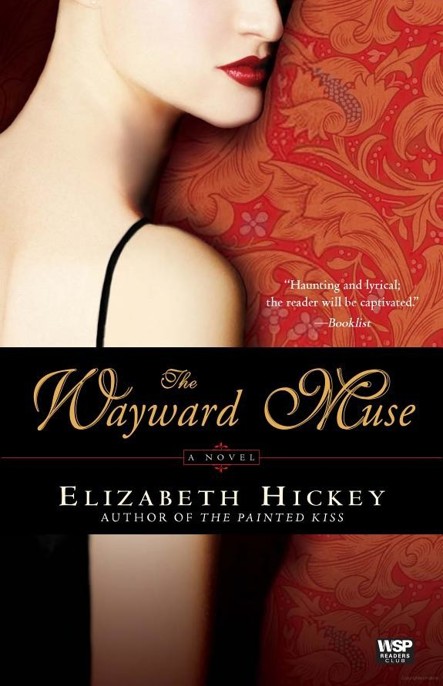

The Wayward Muse

Authors: Elizabeth Hickey

The Painted Kiss

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2007 by Elizabeth Hickey

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN-10: 1-4165-3899-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-3899-8

ATRIA

BOOKS

is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

For Jonathan

Many thanks to Kim Witherspoon, Greer Hendricks, Catherine Drayton, Rosemary Ahern, Suzanne O’Neill, Eleanor Jackson, Lori Andiman, Hannah Morrill, and Meryl Moss. I am indebted to Jasper Selwood and, as always, to my husband, Jonathan Selwood.

J

ANE

Burden was considered the plainest girl on Holywell Street, and that Oxford slum was home to many worthy contenders for the title. Mary Porter, who was afflicted with a lazy eye and copious freckles, lived there, just across the street from Alice Cunningham, who had crooked, discolored teeth and thinning hair. Number 142 was the residence of Catherine Blair, whose neck and ear had been horribly burned when she was a baby, and whose left leg was somewhat shorter than the right. But even she was considered marginally better looking than Jane.

Though Jane had no discernible deformities, her neighbors had their reasons for attributing to her a surpassing ugliness. First of all, she was tall. There were, perhaps, young women who could carry this height gracefully, but Jane was not one of them. Self-conscious, she stooped. Her limbs were ungainly and she often stumbled, or knocked into tables, or hit her head on something. Her neck was very long, and in spite of her dressmaking skill, her sleeves were always too short and her bumpy, bony wrists stuck out awkwardly.

She was also too skinny. She had no breasts to speak of, though she was already seventeen, and no hips. The old ladies shook their heads and told her mother that she would not have children. When she was reproached with this, she thought to herself that it was terribly unfair to be blamed for something that was not her fault. She couldn’t help it that her father and her brother claimed the largest share of the thin vegetable stews and coarse loaves of bread that were all they had. Of course, somehow her sixteen-year-old sister, Bessie, who had as little to eat as she did, still managed to have rounded cheeks and a respectable bosom.

Jane’s hair was as coarse as a bristle brush and curly. Occasionally she used a hot iron in an attempt to create orderly waves, and she regularly stole from the stable the oil used to shine the horses’ coats, but neither iron nor oil worked as well as she would have liked.

But it was her expression that truly made Jane Burden plain. For she seldom smiled, and her green eyes, which might have been considered striking on another girl, were empty. They weren’t sad; sadness could be fetching. They were not grave and serious or soft and pleading or tearful and melancholy. They were blank. Jane’s eyes told everyone who met her of her misery and her despair. They told of a girl who had ceased to hope for anything, who had gone deep inside herself to withstand her lot. It made the others uneasy.

Jane fretted about her ugliness, of course. A poor girl’s looks were all she had, and without them she could never hope to marry. Without marriage her life would be even worse than it was now. If she was lucky, she could work in the kitchens at one of the big estates. If she wasn’t lucky, she’d be a scullery maid in a household one step above her own.

But brooding only made the situation worse. It put a wrinkle of worry between her thick, dark brows and twisted her bow-shaped lips into a grimace.

On this day, however, her lack of beauty was not foremost among her worries as she descended the vertiginous cellar stairs. Her primary concern was supper. Her mother would expect the meal to be ready when she stumbled home from an afternoon of gin and neighborhood gossip, and Jane wasn’t sure she could fashion a stew out of the little they had. Were there any carrots left at the bottom of the bin? Were there any onions that weren’t rotten, or any potatoes that weren’t black and bitter? Perhaps she could send Bessie out to look for some mushrooms.

It wasn’t until she reached the third step that the stench of fermenting urine and excrement enveloped her. She gasped and nearly fell, gripping the rickety banister for support.

“Bessie!” she shouted back up the stairs. “It’s happened again!”

Their house always stank of waste, of course; it was next to the Holywell Street privy. Jane had grown accustomed to it. But the strength and power of the foul odor was so strong she gagged and retched into her apron. When she was finished she untied it and tossed the soiled garment over the banister. Then she forced herself down the steps and into the cellar. She held her candle high and scanned the walls.

Her shoes slopped in mud. She followed the wretched stream to its origin, a crack in the mortar of the south wall, two feet from the floor. Human feces was oozing through and dripping down the stonework.

Jane heard her sister at the top of the stairs.

“Is it the privy?” Bessie cried.

“Of course it’s the privy,” snapped Jane. “Bring me the mop and bucket.”

“Why does this always happen to us?” Bessie whined. “Why are we so unlucky?”

“Luck has nothing to do with it,” said Jane grimly. “Now, hurry. And bring me a rag, too. We need something to stuff in the crack.”

“We need a new house,” muttered Bessie, but she did as she was told.

Bite your tongue, thought Jane. They had lived in four houses in three years, each more terrible than the last. Though she could not imagine what could be worse than living next to the privy. There was the smell, of course, and the periodic flooding, but what Jane hated the most was the fact that everyone on the street walked by their house to use it, stopping to peer in the windows and make rude comments.

The house was hardly more than a cottage, with one room for eating and cooking and another where the five of them slept on straw pallets. It had been made, as many of the street’s houses had, from river rock that had been broken into brick-size pieces, but it had not been made well. The entire structure listed to the left, and the windows and doors weren’t true. It looked as if it might collapse at any moment. In fact, one of the street’s houses had collapsed a few years before, killing a woman and three children, “and some very good laying hens,” as Jane’s mother had put it.

No, she couldn’t imagine anything worse. Even to live out in the open, in the rain and snow, might be uncomfortable, but at least there would be fresh air.

Bessie appeared at the top of the stairs.

“How did it happen?” she asked, holding out the mop, bucket, and rag.

“The night soil men must not have come,” said Jane. “Or there’s a hole in the container.”

“Well, I’m not going to mop up that filth,” Bessie announced. She sat down on the top step and smoothed her skirt as if she were attending a luncheon party.

“Do you know how furious Mrs. Burden will be if she comes home and finds the cellar flooded with this?” said Jane.

“Mrs. Burden will be too drunk to notice,” said Bessie. To each other, they never called their mother Mum or Mummy, but only Mrs. Burden.

“She’ll notice when there’s no dinner, and all the vegetables are ruined,” said Jane. But Bessie would not be moved.

“You know there wasn’t anything down there worth eating, even before it was submerged in filth.” She pulled her needle and thread out of her apron pocket. “I’ve got sewing to do. There’s a tear in my blue tarlatan, and I wanted to wear it to the theater tomorrow night.”

With a sigh Jane went back into the muck of the cellar. The fetid sludge had risen to her ankles. She was concerned that the pressure on the wall might bring the whole thing down. Jane could only pray that stuffing the crack would hold it until someone, her father or the neighborhood mason, could patch it.

Jane filled the bucket and carried it upstairs and out into the street. She didn’t want to dump it back into the leaking privy, so she used the drainage ditch next to the Gibbons’s house. Bessie held her nose daintily each time Jane passed. After fifteen trips the leak in the wall had slowed to a trickle but the dirt floor was still a morass. Jane went to the ash pit and filled her bucket with ashes. She threw them down on the cellar floor. The smell was still horrific, but there was nothing to be done about that.

Jane heard shouting from upstairs. “Why is the fire out? Where’s the supper? Jane? Bessie?”

Their mother was home.

Jane trudged up the stairs. Her shoes and the hem of her skirt were soaked with brown liquid. Her blouse was gray with ash, and her face and hair were streaked with ash and sweat.

Ann Burden stood rather unsteadily in the doorway. She’d been a farm girl once, and had the freckles and the lines around her eyes to prove it. Never a beauty, the years of hard work, first in the fields and then in Oxford’s most squalid neighborhood, had taken their toll. One of her hips was higher than the other and rolled when she walked, or rather, limped. Everything about her was hard: her eyes, her jaw, her sinewy body. Only when she was drunk did her features soften into maudlin self-pity.

When she caught sight of Jane, she screamed with fury. Jane reflected that, in a way, she was lucky because she was too disgusting to be hit. To hit her, her mother would have to touch her.

“What have you done?” Mrs. Burden hissed.

“The privy overflowed again,” said Bessie helpfully.

“So you thought you’d go swimming in it?” her mother said sarcastically.

“I was trying—”

Mrs. Burden cut her off. “Trying to track that filth all over the house? Trying to disgust me more than you already do?”

“I was trying to clean up the mess,” Jane said. She felt like crying, but that would only enrage her mother further.

“Useless girl,” said Mrs. Burden. “What did I ever do to deserve a daughter like you? Ugly as an old shoe, you are, and twice as worthless.”

Jane said nothing to her mother because what was there to say? The only thing to do was to let the tirade run its course.

“I told her we should wait until you got home, but Jane never listens to me,” said Bessie.

“Shut up, Bessie,” said Mrs. Burden, “and start the supper. I want to speak to Jane alone.”

“What will I use for vegetables?” whined Bessie.

“Go down to the cellar, find something that looks usable, bring it up, and wash it off,” said Mrs. Burden, not looking at her. Bessie hesitated.

“But—” she began.

“Go!” shouted Mrs. Burden. With a little squeak Bessie ducked her head, as if to ward off a blow, and was gone.

Mrs. Burden beckoned Jane into the kitchen. She lumbered over to the rocking chair and lowered herself onto it with a groan, but Jane knew better than to sit. She stood in front of her mother and waited.

“I met Mrs. Barnstable tonight,” said Mrs. Burden. “You are to walk with her son Tom this Sunday after church.” She smiled slyly as she waited for Jane’s reaction.

Jane’s throat closed. Her collar was choking her. Tom Barnstable was a tall, gangly youth of twenty with a walleye and a face erupting in pustules. His name was ridiculously appropriate, as he and his father both worked at the stable with her father.

“Think you’re too good for him, don’t you?” said Mrs. Burden, watching her face. “Well, let me tell you something. With your looks you’d be lucky if Tom Barnstable would have you. And believe me, I’m going to do everything I can to make it happen. You’ll not be hanging around here, a millstone around my neck until the day I die, if I can help it.”

“I won’t go,” said Jane faintly. “Tom is a bully. He hits his little sisters; I’ve seen the bruises.”

“An ear boxing or two would do you good,” said Mrs. Burden. “I’ve spoiled you, letting you go to that school, letting that Miss Wheeler lend you books. You’ve gotten above yourself. I have a feeling Tom will keep you in line.”

“Please,” whispered Jane.

“You’re going to walk with Tom on Sunday. You’re going to wear Bessie’s pink bonnet, which doesn’t help much but at least gives your face a little color, and you’re going to be as charming as you can possibly be,” said Mrs. Burden. “Now get out of my sight.”

Jane ran out the door and into the street. It was not yet dark and she hoped that she would not meet anyone. Her clothes were still damp and the wind chilled her. She ran down the street toward town.

Jane sometimes imagined that she lived far away from Oxford. Usually she pretended that she lived in the Balearic Islands, which she had read about in a geography book. It was warm there, she knew. You could live in a raffia hut lapped by the sea and eat lobster stew by the bowlful. This time she tried to imagine that she lived in London, in a brick town house on a fashionable street. She would have a cook who would make lamb stew, piping hot and fragrant with rosemary, and rolls dripping with butter. For dessert, she would eat sponge cake with caramel sauce, and strawberry trifle. Jane would wear goat’s-hair shawls from India and fine silk dresses from China.

Sometimes Jane’s daydreams comforted her, but not today. She could not escape the fact that she was cold and dirty. She couldn’t pretend that she was pretty. She was ugly and she must marry Tom Barnstable or no one.

Jane finally stopped at the end of Holywell Street; she couldn’t go on into town covered in filth. She tried to think of somewhere else to go, but there was nowhere else, so she turned and started back.

Halfway home she heard a cat yowling and she quietly stepped into a doorway, hoping not to be seen. A tortoiseshell cat hobbled pathetically by her, dripping blood from its ear. Then she heard pounding footsteps and Tom Barnstable ran by, a stone in his hand, an expression of glee on his face. He did not see her.

My future husband, she thought, and then she did cry, sliding to the hard stone step and burying her face in her stinking skirt.