The Willows and Beyond (17 page)

Read The Willows and Beyond Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson,Kenneth Grahame

Tags: #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

The next morning dawned crisp and clear as Toad’s honoured guests Rat and Mole came downstairs to join Toad and his ward for the sumptuous Christmas breakfast that Toad Hall traditionally served its guests. This continued long enough for Badger, Grandson, Otter, Portly and finally Nephew to join in as they arrived during the course of the morning.

It was then that Toad enjoined the staff to leave their own festivities backstairs to share the moment when a hall (however grand), or a house (however humble), becomes a simple home and safe retreat, as symbolized by the lighting of the Yule log.

To the Rat was accorded this great honour, in the hearth of the banqueting hall where Christmas dinner was later to be served. Happy tears came to his eyes as the fire took at the first touch of his spill, and with the birth of its flames and warmth Christmas began for one and all.

“Have you made your wishes?” asked the Mole of Young Rat.

“For peace and happiness, yes,” said he.

“And for yourself?”

“I have all I want, sir; you’ve all been very good to me.”

“There must be something you want for yourself alone,” said the Mole kindly, “so wish again.”

Young Rat turned back to the flames and pondered the point long and hard, and then the Mole saw him grow still as he made his wish, and he hoped it might come true.

“Champagne all round!” cried Toad, who on such occasions as these did not stand on ceremony and included everybody, even the bootboy.

If that meant that younger members of the staff became a little giggly, and the deputy butler a shade wobbly, and the housekeeper inclined to forget herself and kiss the butler on the cheek — and if it meant that the Badger had to sit down for a moment, and the Mole could not stop grinning, and the Otter chuckling and Portly and Nephew laughing, well, what did Toad of Toad Hall mind? His only desire was to see that all in his care were happy and content, just as they had been in his father’s day, and

his

father’s before that.

If, too, the staff retreated back to their own quarters full of praise for their employer, it was not because he proffered them a glass of champagne once a year, but because in that offering, and in the good and generous words he spoke in praise of them, they knew that in Mr Toad’s heart, despite his eccentric and sometimes self-centred ways, Christmas was

all

the year, for his friends, for them and for Toad Hall.

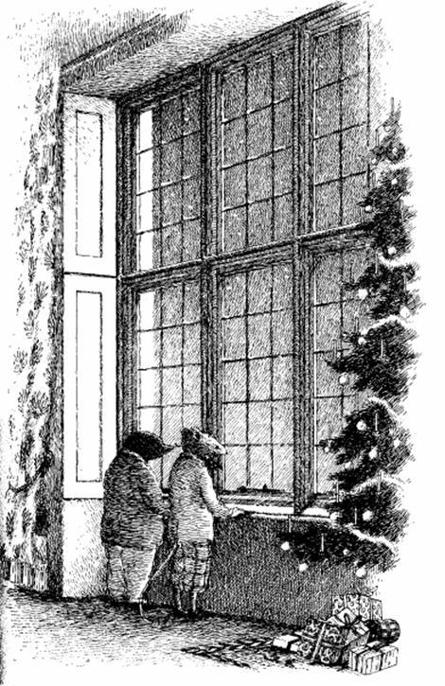

Yet for one among them that day Christmas seemed a little overwhelming, and this was Young Rat, whose first it was. Try as he might to join in the games of blind-man’s-buff and bobbing apples, which he had never played before, others, like Nephew, could not but notice how sombre he seemed at times, and how inclined to find a place a little apart, and stare out at the River across the snow-bound garden.

“Anything wrong?” asked Nephew, who knew that with Young Rat, as with Ratty, direct talk was best.

“I miss my Pa,” said the youngster, “and wish he could see all this. The Yule log Mr Ratty lit:

he

mentioned logs. The tree with all those candles on it: he said

he

had a tree. The people, he had those about him as a lad. The games:

he

knew ‘em all and more.

“Well now,” murmured Nephew gently, “I think he would have been glad to see you so well set and able to enjoy all those things in his place.”

“He would,” said Young Rat, “but how much better if he were here as well!”

Yet Christmas would not be the same without such quieter moments of reflection and regret as these, for it is right to reflect upon the losses of the year and lay them to rest, just as it is good to celebrate the triumphs and the coming of a new season, and new hope.

“Come on,” said Nephew gently, “it’s time for dinner.”

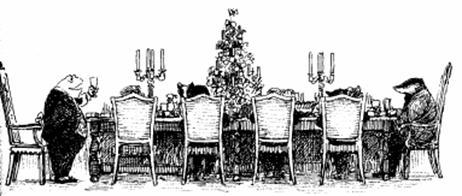

The great dining table had been laid the day before, though that morning it was further dusted, manicured and finished, and embellished with crackers, streamers and candles, the best silver and the mightiest serving spoons and ladles, carving knives and forks. In the centre was a great decoration of holly and ivy all tinselled gold and silver.

“I shall be making a great many speeches in the course of the next five hours or so,” cried Toad once everybody had sat down but before any food was served, “and this is merely the second!”

“The third,” said the Otter.

“I make it four,” whispered the Mole to the Rat, who sat in the place of honour at the left hand of Toad.

“It was my father’s tradition and has been my own —and one day I pray it will be that of Master Toad here as well — to propose a toast to the Uninvited Guest, whose place is always set here at my right side, though he never turns up, I’m glad to say, leaving all the more for the rest of us! Badger, you remember the old days and my father better than any of us, so would you propose that toast?”

“With great pleasure,” said the Badger, rising. “For I remember my first such dinner here, in the old Hall before the fire, and Mr Toad Senior himself offering up that hallowed toast. He offered it, as I now do, in the name of those who have no place to go this day, no company to keep, no table at which to sit. People whose lives and circumstances have not brought them family or friends as we have, or have taken them far from those they love on this day when they have most need of them.

“Therefore, in Toad Hall, as in all true Christmas homes, a place is laid for the Uninvited Guest, that we think of him before we eat and drink; and reflect upon the fact that were he to come and join us, the greater blessing would be ours! And what is more. .

How the Yule log flamed and crackled as the Badger spoke, and how the embers glowed! How bright and cheerful the faces of those who listened to his words, nodding their heads in approval, holding their well-charged glasses ready for the toast.

Outside Toad Hall the winter wind drove the falling snow against the casement panes, to pause, swirl and settle. Along the River Bank, the old dead sedge stems trembled, the leafless willow branches swung dark against the driving sky and the River’s surface flurried with the breeze, and all seemed devoid of life.

Yet there

was

one lost and lonely soul abroad.

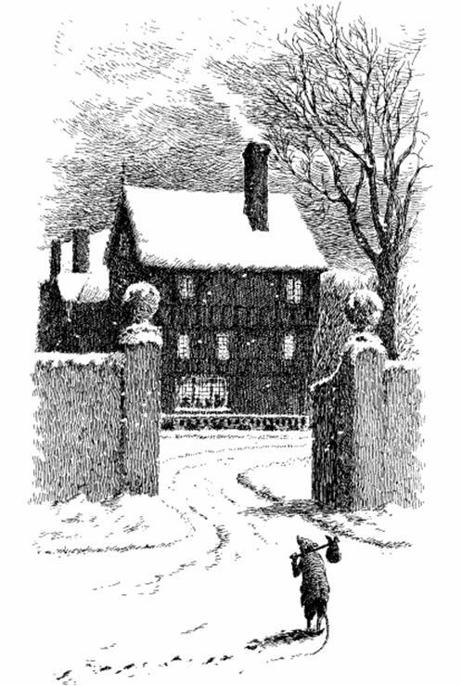

How slowly he came, he who had no certain place to go that day! With what sinking heart he had battled for days through the snow-obstructed lanes of the country south of the Weir, sheltering beneath hedges or in a ruined barn through the long, cold nights, wondering if, come the morn, he should turn back. Yet he had not done so, driven on by hope, though he was shivering now and hungry, and as cold as bleak despair.

He who had no company to keep that day had reached the River Bank, thinking perhaps that here at last he might find respite, and a welcome of a sort, but found instead homes devoid of light and occupants. No light in the Water Rat’s house where his slow steps first brought him; nor next in the Otter’s, though there a hanging on the door reminded him that for some it was a happy Christmas, for some. Not knowing those parts well, and thinking he might find shelter in the Wild Wood, it was that way he turned next, and to the Badger’s home he came.

“No light again!” he muttered. “And nobody at home!” But then he saw two sets of prints leading from that old door, and though they were nigh filled up with snow he followed them, if only to give himself the forlorn sense he had company, though it had gone before.

“Hmmm!” he said, reaching the Iron Bridge. Thinking its hump almost too steep for his tired, cold legs, he pausing awhile to stare into the River. Then with a sigh and a shake of the head, he turned from the dark waters below, and began to climb.

It was then he had sight of something to cheer his eye, and lighten his heart, if only as an outsider passing by. He saw the lights of Toad Hall, warm and bright already in the darkening afternoon.

“Ah, sweet Christmas!” said he. “Those were the days!” Then down the other side of the Bridge he walked, alongside the wall about Toad’s estate, till he reached the gates, where he paused once more and stared again at the lights. Why, were those gentry folk he could see through the windows there?

“They’ve had a feast and a half, I’ll be bound’ said he, without envy or malice, “and, who knows, tomorrow, if I can find a place that will give me work along the way, maybe I’ll find

my

Christmas fare.”

“—and therefore, my friends,” said the Badger, concluding his toast, “I ask you now to rise and raise your glasses and join with me in a toast to the Uninvited Guest, wherever he may be, that he may find comfort and welcome this day, and bring a blessing upon the house he honour’s with his presence!”

They raised their glasses high, and each in his own way, but all with warmth and sincerity, uttered the words:

“To the Uninvited Guest!”

What good spirit rose among them then and travelled out of the casement and across the snow-covered lawns, as they sipped their drink and pondered upon that person Badger had evoked? And what species of magic is it comes at Christmas, to make a mystery of simple candlelight and bring forth hope, and cause the Yule log’s flame to shine with a light brighter and more far-reaching than is seen on ordinary days?

Was it then the great Friend and Helper who whispered these words on the winter wind, “Yet turn about, my friend, for seek and ye shall find”?

For as Badger, Toad and all the others made that toast, he who had travelled so very far to the River Bank, and had thought to journey on, turned back and stared again at the lights of Toad Hall, and remembered an ancient tradition he had known his father keep.

“The Uninvited Guest, dare

I

be he?”

“Yes,” whispered the wind, “you may”

Toad and his guests had already sat down again and were ready to be served when there came a tentative knocking at the Hall’s great front door, and the Butler looked enquiringly at Toad.

“Why, go and see who it is and if he looks half hungry invite him in, and if he doesn’t, invite him in all the same!” cried Toad, for though unexpected visitors had called upon Toad Hall from time to time in Christmases past, none had ever come at this hour, at this auspicious moment, with that good toast still ringing in their ears.

All conversation and serving ceased, for there was about that knock something that stilled them all. They heard the door open, they heard quiet voices, they fancied they heard a polite protest of some kind, as of someone who had not expected to be invited in to more than the scullery, and that only for a moment or two.