The Willows and Beyond (5 page)

Read The Willows and Beyond Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson,Kenneth Grahame

Tags: #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

“Uncle, did you see?” whispered Nephew a little later. The Mole nodded with resignation, and told Nephew to say no more about it, the Rat was already in a bad enough mood as it was.

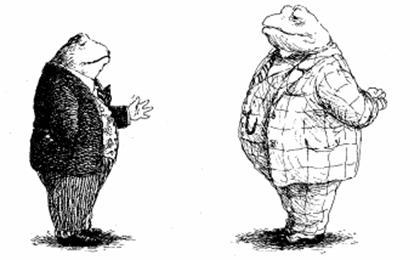

Of course he had seen, seen all too clearly: a gentleman of large and stocky build in the front passenger seat of the motor-car, gagged and bound. And in the rear two more, clearly dealt with in the same way While in the driver’s seat, scarf flying, laughing and behaving in a manner that was entirely reprehensible, was a toad who looked very much as Toad used to look in days gone by, when he was enjoying himself at other people’s expense.

“But, Pater,” which is what Master Toad called his guardian when he knew he had gone too far and felt that a show of respect might not go amiss, “had you only

told

me that the gentleman who claimed to be in your employ had been sent by you to Dover to see me safely home, and not to abduct me and demand a large ransom for my safe return, which is the impression he very soon gave, then

of course

I would not have treated him as I did.

“But I must say that my suspicions regarding his claim to be a former policeman of considerable experience were very amply confirmed when he allowed himself to be bound with his own handcuffs and gagged with his own handkerchief I know how you detest constables, along with lawyers, churchmen and others who generally seek to curb our liberties, and I could not imagine for one moment you would employ one, let alone three. Really I cannot be blamed for anything that happened!”

Toad did not for one moment believe a word of this nonsense, but then the ex-constable had not made his case easier by being duped by a mere youth. Toad knew perfectly well that he would have tried the same trick, and that he would have felt as smug as Master Toad now looked if he had pulled it off.

Yet Toad was not entirely down-hearted by the nature of his ward’s arrival, for whatever the rights and wrongs of the affair it gave him an early opportunity to lay down the law regarding duties and responsibilities, much as he had outlined them to the Mole some weeks before. To his surprise and relief Master Toad did not raise any objections, rather the opposite in fact, for he claimed to be very eager to get on with some schoolwork, and overjoyed to have a timetable to follow, and strict meal times to observe.

“I am in need of improvement,” said Master Toad piously, “for I ‘ave wasted my schooldays in laziness and foolishness and now I must work and be good.”

Toad could scarcely believe his ears — indeed he did

not

believe his ears, and concluded that far from knocking some sense into the youth, the Grand Tour had encouraged him towards a high level of accomplishment in acting, which might, if all else failed, help Master Toad find ready employment upon the stage.

“When did you come to realize the errors of your ways?” asked the suspicious Toad.

“It was when I was in Rome at confession after ‘oly Communion in St Paul’s Cathedral. I see a light, I hear a voice saying, ‘Henri, be good, study ‘ard,’ and I confess my sins to the padre.”

“St

Paul’s

you say?” said Toad evenly.

“Exactement!”

came the reply, and the over-confident embellishment gave the game away, “I ‘ave seen the name upon a board outside: ‘St Paul’s, the Pope’s Own Church.’ ‘Ave you been to Rome, Monsieur Toad?”

“As a matter of fact, I have — my father sent me at about your age, for much the same reason, and with about the same effect. In those days the cathedral was called St Peter’s, but perhaps —“So many impressions, so many places, so easy to confuse,” said Master Toad airily, affecting not to notice that his cathedral visit had been exposed as fraudulent, but in truth considerably discomforted.

“All the more reason to work hard at your said the ruthless Toad, who felt very pleased with himself at having so easily demonstrated who held the whip hand in the Hall. “Now you have time for at least two hours’ work before teatime!”

Whether or not Master Toad really used the next two hours for work mattered not a bit to Toad; he was quiet and he was obedient, and up in his room he was, relatively speaking, out of harm’s way.

Later, over tea, the two began chatting again, and very soon Toad was thoroughly enjoying an engaging account of the trials and tribulations, the triumphs and the disasters, such as any young person, journeying about the Continent, albeit first class and via the best hotels, is likely to experience.

Finally, matters came round to the River Bank, and Toad was gratified that his young friend showed rather more interest in the doings of the Mole and the others than he had earlier in the year, and even expressed a desire to see his friend, Mole’s Nephew, at the earliest opportunity.

“I hope there will be no objection, when my work is done, if I borrow the motor-launch —“

“There is every objection,” said Toad, happy that he had foreseen this request and, having considered the dangers inherent in granting such permission, had decided that a total veto was the best policy. “In any case,” he added, “Ratty and Mole are themselves using it just now, so it is not even here.”

“Aah… and what about that motor-car that gave me such a pleasing journey from Dover?”

“Rented,” said Toad shortly, “and already on its way back to Dover. The former constable has taken it, along with his incompetent colleagues.”

“Aah … “said the defeated youth.

Toad rather expected some complaints at this point but Master Toad made none. Rather, he asked in a sweet and winning way what “educational exercise” Toad had in mind for the following afternoon.

Toad rose from the chaise longue in which he normally took tea and paced busily about the conservatory He was rather excited about the exercise he had organized, and a trifle nervous too, for it was not something he had often engaged in if he could possibly avoid it. But just lately this particularly activity had come into fashion and Toad was not one to be left behind. More to the point, every expert lecturer and author upon the subject (he had been to several lantern slides and cinematograph lectures, and had acquired a large quantity of helpful books, which he was hoping shortly to find time to read) made the point that this pursuit was especially healthy and educational for its followers.

“Pater, what is the exercise to be?” repeated his ward. “We shall be going hiking,” said Toad, with as much enthusiasm and confidence as he could muster.

“‘iking?” repeated Master Toad in some considerable surprise. He thought he knew what the word meant, but he could not connect it with his guardian.

“Hiking during the week, and cycling at weekends,” said Toad, weakening a little, for the cycling was a reserve activity for which he had little relish. The last time he had been upon a bicycle he had been pursued by His Lordship’s pack of hounds, who had caused him to crash headlong into a hedge and might have devoured him (as he recalled it) had he not fought them off with his bare hands.

He had decided, however, that a guardian must suffer in the course of his duties, and along with the two sets of walking gear he had ordered from a prestigious department store in the Town, which prided itself on supplying anything to anybody anywhere, even in the furthest-flung part of the Empire, he had also ordered two gentleman’s cycles.

“But hiking’s the thing,” said Toad. “The most exciting and ennobling form of exploration there is!”

“Le

‘iking is exploring without the convenience of ‘orse, motor-car, train, omnibus, bicycle, or any other way of transporting one person or more from ‘ere to… there,

non?”

suggested Master Toad with very considerable distaste, gazing down with enormous sadness at the ground beneath him.

“Le

‘iking is on the feet only, yes?”

“Hiking,” said Toad, who was pleased that his ward understood at least the rudiments, and not displeased that he saw this new pastime as a challenge, for he believed that to be effective educational exercise would have in some way to be hard and strenuous, “hiking, I believe, is really the only way to get about and see things. When I was younger I foolishly thought that, say, a caravan might —“

“O, yes,

monsieur!”

exclaimed Master Toad, who not five minutes before would have refused to go anywhere near a caravan.

“And then I was seduced, that is not too strong a word for it, by motor-cars —“

“Yes, they are wonderful, so perhaps —“Then I settled upon an aeronautical future for myself, and —“

“Pater, I wished very much to ‘ave a word with you about flying lessons, because —“

“But none of them offers the same combination of healthy exertion, freedom of choice and demands upon the character and intelligence as hiking.”

“You ‘ave done this ‘iking before, then?” asked Master Toad softly.

Toad had never in his life willingly hiked anywhere, to his knowledge. On those few occasions when he had found himself in wild parts without some form of conveyance, usually when a fugitive from the law, he had devoted his considerable enterprise to getting back to normality as quickly as he possibly could, and into a comfortable chair at home.

Except… now he thought of it, there

had

been an occasion, lasting many weeks, when Toad had wandered free across the land, weeks which he could barely now remember, though there were remnants of them still in his fickle and errant memory, when he had woken up under hedgerows, shared meals by the fires of friendly itinerants, and gone to sleep hungry by the light of the stars.

That episode had occurred after his release from one of his sojourns in gaol when, for reasons best forgotten, he did not feel able to show his face about the River Bank for a time. Now it was all coming back to him, and he saw it had not been all bad.

“Yes,” said Toad simply and truthfully, “I

have

hiked as it happens, which I can see surprises you considerably Not much, it is true, but enough to know the truth of what I say about this excellent pursuit. Therefore, young sir, we shall hike at least five days a week, and if you refuse or resist or fail to look anything but pleased and delighted with this pastime, I shall —“

“Yes, Monsieur?” said Master Toad with the easy insolence of one who does not believe for one moment that his pater will do anything at all to harm him.

“— I have decided that I shall no longer pay your school fees and that you must go forthwith to work!”

Toad had never offered any real sanction to the youth before and was rather surprised to find himself doing so now, but there had been such an irritating confidence in the way that “Yes, Monsieur?” had been uttered that a new resolution to be firm and severe had come over him.

“O

non!”

cried the youth, staring up in considerable dismay “Not real work — with my hands!”

Master Toad recognized that there was a new tone in Toad’s voice. He had been much looking forward to going back to school where all his friends were, but now … O, how horrible Toad Hall was! How terrible his guardian was!

“Well?” said Toad.

“I shall be so ‘appy to ‘ike every afternoon before tea,” said the youth compliantly, though, in truth, he was already planning how he might evade in every way possible this most loathsome and humiliating of pastimes.

“And now,” said Toad equably, recognizing that look in the youth’s narrowed eyes very well, for he had looked thus at his father years ago, “you have an hour before you need to change for dinner. Badger is coming, and Mole, Ratty and Otter if they are back from their journey to the Town. You know how stimulating you find their company”

“Yes,” agreed Master Toad reluctantly, doing his best to put a brave face on it. “But Nephew and Portly — do they not come?”

Toad smiled broadly and put an affectionate hand upon his ward’s shoulder, for he felt he had gone far enough.

“Don’t worry. They are all coming. I would not be so heartless as to impose my old friends upon you without asking along some of your own. They have greatly missed you this summer, and they want to hear all about your adventures and misadventures upon the Continent.”

For the first time since his return, Master Toad grinned. He went back to his books with renewed vigour, quite forgetting the passionate dislike of Toad he had felt only moments before, but feeling instead that it was perhaps good, after all, to be home.