The Winter Ghosts (12 page)

Authors: Kate Mosse

‘Nothing here can harm you,’ she said. ‘No one.’

After her long silence, her voice was startlingly loud, and I swung round in alarm.

‘Harm me? What do you mean?’

But her eyes had clouded over again. I was baffled. Didn’t know what to make of it, any of it.

I turned to my right. The man was still hunched over the remains of his meal, but he had stopped eating. Up and down the table, across the room, it was the same story. Anxious faces. Frightened faces. Those to whom Guillaume Marty had introduced me earlier: the timeworn Maury sisters and Sénher and Na Bernard, holding hands; widow Azéma, her old milky eyes looking into the middle distance. Again, I searched for Madame Galy, knowing the sight of her would be somehow reassuring, but still could not see her.

The hall seemed colder and I felt the same sense of desolation when I’d first arrived in Nulle, except now the sadness was tinged with fear.

At the far end of the room, an altercation broke out. Voices raised, the sound of a bench being overturned. At first, I assumed it was some kind of drunken brawl. It was late and the wine had flowed freely all night.

Fabrissa turned towards the entrance. I did the same, at the precise moment the heavy wooden door was flung open. Two men strode into the hall.

‘What the Devil . . .’

Their faces were concealed beneath square iron helmets and the candlelight glinted on their unsheathed swords, sending flashes of gold dancing around them like sparks from a blacksmith’s anvil.

For a moment, nobody spoke. Briefly I wondered if this was part of the evening’s entertainment. Some absurd historical re-enactment of the original, long-gone

fête de Saint-Etienne

taken too seriously. Like the costumes or the traditional foods or the troubadour and his

vielle

.

fête de Saint-Etienne

taken too seriously. Like the costumes or the traditional foods or the troubadour and his

vielle

.

Then a woman screamed and I knew it was not. Panic took hold. My uncouth dining companion scrambled to his feet, shoving me with his elbow. I fell against Fabrissa and felt her heavy hair briefly touch my skin, a subtle scent of lavender and apple.

‘Freddie,’ she whispered.

A small group of men was attempting to drive the intruders from the hall. Some brandished hunting daggers, drawn from their sheaths on their belts. Others grabbed at whatever makeshift weapon came easily to hand: pieces of wood, irons from the fire, even the heavy skewer on which the meat had been served.

The blades jabbed and sliced the air, though never connected. It was an unequal fight for, although the soldiers had the advantage of heavier weaponry, they were overwhelmingly outnumbered. The crowd was shouting and pushing forward now in a mass of arms and legs. The cry went up to barricade the door. The mood was ugly, likely to escalate. I did not want Fabrissa to be caught up in it.

And despite the exhaustions of the day, despite the fact that it must have been well past midnight, I felt suddenly alive. Purposeful. Adrenalin coursed through me. This time I wouldn’t funk it.

I reached for Fabrissa. ‘We must leave.’

‘Are you sure?’

Her tone was grave, as if my rather obvious suggestion held some significance beyond simple common sense. I took her hand. An intense heat shot through my veins, carried the singing in my blood to the base of my spine. I seemed to grow taller. I felt capable of anything.

‘Come on. Let’s get you away from here.’

Did I manage to keep the smile from my face? Looking back, I’m sure I did not because, finally, my hour had come. All my life I’d been second best. Never the right man for the job. Not invincible.

Not George.

That night it was different. Fabrissa had put her trust in me. Had chosen me. It was a gift I’d never thought to receive. And even now, more than five years after the event, and in the light of everything that subsequently happened, the ecstasy of that moment will never leave me.

‘Is there another way out?’

She pointed to the far corner of the hall.

The soldiers had been driven back, but now there was fighting everywhere, between those marked out by a yellow cross and those not. I felt I was observing the scene from above, disconnected and yet at the heart of things. Holding on to Fabrissa tightly, I launched forward into the mass of bodies, swimming against the tide. We ran, she and I, clumsily hand in hand.

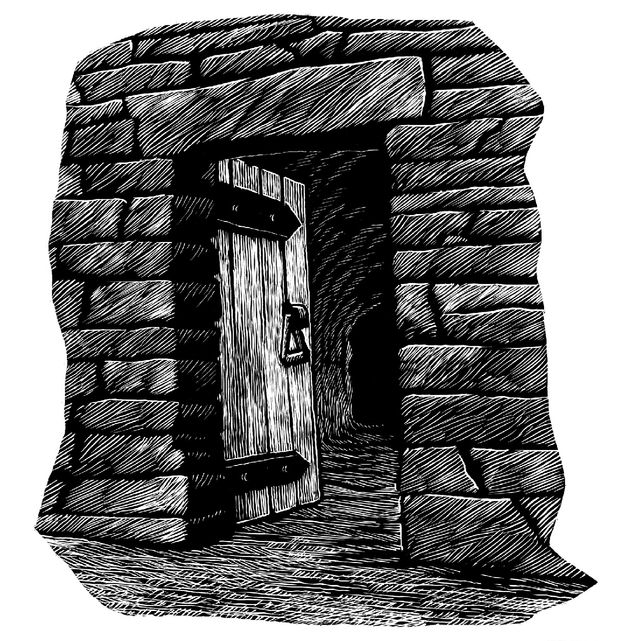

‘Through there?’ I said, raising my voice to be heard. I could see a small door set in the wall, partially hidden behind a pyramid of wooden chairs and a heavy wooden chest with a metal clasp and bands.

She nodded. ‘It leads to a tunnel that runs beneath the Ostal.’

With a strength I didn’t know I possessed, I hauled the chest aside and tossed the chairs out of the way as if they were made of pasteboard.

Was I scared? I should have been, certainly, but I don’t believe I was. Instead, what lingers in my memory is my single-minded determination to get Fabrissa to safety. I unhooked the latch and pushed at the door with the flat of my hands until there was a gap wide enough for us to slip through. We ducked under the low lintel and down into the darkness we went.

The steps were shallow, worn away at the centre, and I held her hand even tighter to prevent her from slipping. In the hall above, I could hear women screaming and men shouting instructions and children crying. The sound of wood splintering and the clatter of metal on metal. Then the door thudded shut at our backs and we were plunged into silence.

I hurtled forward, but was forced to slow down. I couldn’t get the dimensions of the tunnel fixed in my mind. The air was dry at least, not damp, with a smell that reminded me of cathedrals and catacombs, of all those hidden places lying forgotten across the long and dusty years. A cobweb draped itself across my face, my mouth and eyes. I spat the filigree threads away, though the sensation lingered.

‘Shall I go ahead of you?’ Her voice was soft in the dark. ‘I have been this way before.’

I squeezed her hand to let her know I was fine with things as they were, and felt her return the pressure. I smiled.

‘Where does the tunnel come out?’

‘On the hillside to the west of the village. It is not far.’

The Yellow Cross

We stumbled along in the dark. After our initial descent, the tunnel quickly flattened out for a while, before beginning slowly to climb again. My breath came in ragged bursts and sweat gathered on my temples and cheeks, making my cut sting.

I concentrated on keeping my footing. I could see nothing at all. The roof of the tunnel seemed sometimes to skim my head, and the walls were close enough to touch, but I had no sense of where we were. Fabrissa, though, seemed unchanged. She appeared to be neither tired nor breathless in our claustrophobic surroundings.

So we pressed on, on through the subterranean world, until the atmosphere began to alter. The path grew steeper still, and I felt a whisper of fresh air on my face.

The ground suddenly veered precipitously upwards. The perspective ahead of us slipped from black to grey. Pinpricks of moonlight gleamed around what looked like a door blocking the end of the tunnel.

I sighed with relief.

‘There is a brass ring,’ said Fabrissa. ‘It opens inwards.’

I ran my fingers over the surface of the wood, like a blind man, until I found it. The handle was cold and stiff. I grasped it with both hands and pulled. It didn’t shift. I braced my feet apart, and tried again. This time, I felt the door straining at the hinges, though it still didn’t budge.

‘Could it be barred from the outside?’

‘I do not think so. It is probably because this particular escape route has not been used for a very long time.’

There wasn’t time to wonder what she meant. I just kept at it, pulling steadily, then following it up with a series of sharp jerks, until finally there was a dull crack and the wood around the hinges splintered.

‘Nearly,’ I said, pushing my fingers in the gap between the door and the frame.

Fabrissa put her hands below mine and together we tugged and wrenched until, suddenly, we were outside in the chill night air. Behind us, the door hung loose on its hinges, reminding me of the entrance to an old copper mine George and I had discovered one wet August holiday in Cornwall. He, of course, had wanted to go in, but I’d been too scared.

Different times, different places.

I turned to Fabrissa, standing so still in the flat, white moonlight.

‘We did it,’ I panted, trying to catch my breath.

‘Yes,’ she said softly. ‘Yes, we did.’

We were standing out on a bare patch of ground about halfway up the hillside, to the east of the village. The opposite side of the valley, I realised, from the direction in which I had approached Nulle the previous afternoon. I felt light-headed, intoxicated by the night air, by what we had achieved, by her company.

Then I felt a stab of guilt I could not ignore.

‘I must go back. I have to do something. Help. People could be seriously hurt.’

She sighed. ‘It is over now.’

‘We can’t be certain of that.’

‘All is quiet,’ she said. ‘Listen. Look.’ She pointed down at the village. ‘All is calm.’

I followed the line of her finger and picked out the church spire, the patchwork of houses and buildings and alleyways that made up Nulle. The Ostal itself, white in the moonlight, was directly below us. Nothing was stirring. No one was about. No lights were burning. I could hear nothing but the enduring silence of the mountains.

‘It was all part of the

fête

?’ I said. ‘The soldiers, the fighting?’

fête

?’ I said. ‘The soldiers, the fighting?’

But much as I wanted to be persuaded there was no need for me to intervene, it had seemed too brutal to be mere play-acting.

‘Come,’ she said quietly. ‘There is little time left.’

‘Where are we going?’

‘To a place we may sit and talk a while longer.’

Fabrissa set off down the hillside without another word, giving me no choice but to follow. She walked fast, her long blue dress swishing about her legs. Beneath the swing and sway of her hair, I caught glimpses of the yellow cross. Without thinking about what I was intending to do, I hurried to catch up with her.

‘Wait,’ I said. With a sharp tug, I pulled the tattered piece of fabric from her back. ‘There. That’s more like it.’

She smiled. ‘Why did you do that?’

‘I don’t rightly know. It looked wrong. Like it shouldn’t be there.’ I hesitated. ‘Do you mind?’

I felt her grey eyes sweep across my face, as if committing every part of it to memory. She shook her head.

‘No. It was brave.’

‘Brave?’

‘Honourable.’

While I was still pondering her choice of words, Fabrissa had set off again. I pushed the cross of fabric into my pocket and followed.

‘So, what do the crosses signify? I saw several of the other guests wearing them, too.’

She did not answer and she did not slow down. The night air seemed to shift as she passed, and there was something about the translucent moon-shine that gave me the impression she was made of air or water, rather than blood and bone. I did not press her further. I did not want to disturb the delicate balance between us, and that seemed more important than any questions I might want answered.

The path wound down through the frosted grass. I glanced over my shoulder and saw the mouth of the tunnel diminishing behind us. We were close to the village now, but rather than continuing down into Nulle, Fabrissa led me to a small dewpond halfway down the hillside and indicated we should rest. I sat down on the mossy trunk of a fallen tree, grateful for the chance to take the weight off my feet. The soft-soled boots had begun to pinch.

The sky was beginning to turn from black to inky blue. When I looked back up at the track, I could just make out the silver imprint of my footprints on the grass in the early-morning dew. Dawn was not far away.

I thought for a moment of the strangeness of dew in December, then how queer it was that I was not cold, despite having abandoned my coat and hat in the Ostal. I felt curiously weightless, as though, having spent the night in Fabrissa’s company, I had taken on some of her qualities of delicacy and lightness.

Other books

Horse Charmer by Angelia Almos

The Academie by Amy Joy

Phoenix Ascendant - eARC by Ryk E. Spoor

A Promise to Love by Serena B. Miller

A Year in Fife Park by Quinn Wilde

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin

Hot As Blazes by Dani Jace

Open Country by Warner, Kaki

Newport: A Novel by Jill Morrow

Dark Creations: The Hunted (Part 4) by Martucci, Jennifer, Christopher Martucci