The Winter Ghosts (22 page)

Authors: Kate Mosse

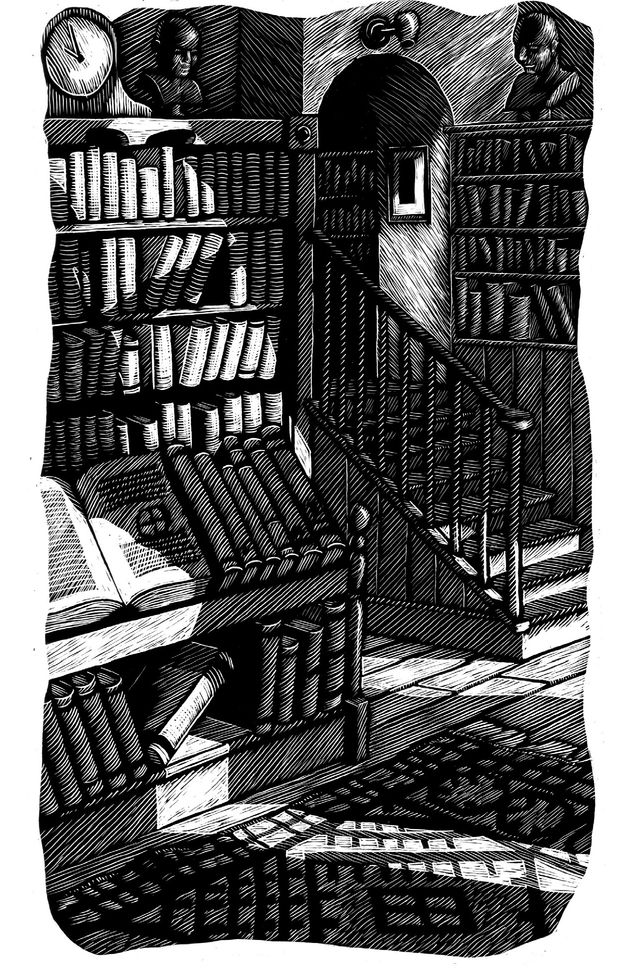

The shadows had lengthened while they had talked. The late-afternoon sun, shining through the metal grille across the window of the bookshop, cast diamond-shaped patterns on the floor inside the bookshop.

Saurat cleared this throat. ‘And for the past five years?’

‘I returned to England. Not straight away, but when it was clear there was nothing . . .’ Freddie broke off. ‘Then, of course, the Slump, and all that followed. My few stocks and shares became worthless overnight. I had no option but to find a way of earning a living. I rented rooms in a house and got myself a job with the Imperial War Graves Commission in London. Modest enough, but sufficient for my needs.’

‘I see.’

‘We unveiled the memorial at Thiepval, to those who died at the Battle of the Somme, on the first of July nineteen thirty-two. My brother’s regiment, the three Southdowner Battalions, went over the top on the eve of the Somme. They took the German front line and held it for a while, but then fell back. In less than five hours, seventeen officers and nearly three hundred and fifty men of Sussex were lost. The following day, the main engagement began.’

‘And since then?’

‘Travelling, around France and Belgium for the most part. I’m one of the team of men responsible for the upkeep of the headstones and the crosses of sacrifice and the cemeteries.’

‘So no one is forgotten.’

‘We remember so that such slaughter is never allowed to happen again. George, Madame Galy’s son, the men of the Ariège, the Southdowners, we must remember them. All the lost boys.’ Freddie stopped. This was not the time or the place.

He took a sip of his drink, then carefully replaced the heavy tumbler on the table and pushed the parchment across the green felt.

Saurat held Freddie’s gaze for a moment. In his eyes, he saw neither expectation nor anxiety, but instead resolve. He realised that, whatever lay within the letter, it would come as no surprise to the Englishman.

‘You are ready?’

Freddie closed his eyes. ‘I am.’

Saurat adjusted his spectacles on the bridge of his nose, then began to read.

‘Bones and shadows and dust. I am the last. The others have slipped away into darkness. Around me now, at the end of my days, only an echo in the still air of the memory of those who once I loved.

Solitude, silence. Peyre sant.

The end is coming and I welcome it as one might a familiar friend, long absent. This has been a slow death, trapped here. One by one, every heart stopped beating. My brother first, then my mother and my father. Now the only sound is my shallow breathing. That, and the gentle dripping of water down the mossy walls of the cave. As if the mountain itself is weeping. As if it, too, is mourning the dead.

We heard them, their footsteps, and thought ourselves safe. We heard the rocks, one by one, being piled up, the hammering of the wood, but still we did not understand that they were sealing the entrance to the cave for good. And this underground city, lit only by candles and torches, once our refuge, became our tomb.

These are the last words I will write. It will not be long. My body does not obey me now. My last candle is burning out. This is my testament, the record of how once men and women and children lived and died in this forgotten corner of the world. I write it down so that those who come after us will know the truth.

I do not fear death. But I fear the forgetting. I fear that there will be no one to mark the moment of our passing. One day, someone will find us. Find us and bring us home. For when all else is done, only words remain. Words endure.

And I shall set this last truth down. We are who we are because of those we choose to love and because of those who love us. Peyre sant, God of good spirits, have mercy on my soul.

Prima

In the year of our Lord, thirteen twenty-nine’

‘Someone will find us,’ repeated Freddie.

Saurat peered at him over the top of his half-moon spectacles. He waited a while as the words echoed into the silence of the books on the shelves of the narrow little shop.

‘Spring thirteen twenty-nine,’ he said in the end.

Freddie opened his eyes. ‘Yes.’

‘More than six hundred years ago.’

‘Yes.’

The two men looked at one another. Only the ticking of the clock and the motes of dust dancing in the slatted afternoon light marked that time moved at all.

‘Have you been back to Nulle?’ Saurat asked.

‘I have. On several occasions.’

‘And?’

Freddie smiled. ‘It is different. A place restored to itself. Monsieur and Madame Galy are still there and their little boarding house is thriving.’

‘No longer living in the shadows.’

‘Not at all. Nulle itself has become quite a centre for walking holidays in the mountains south of Tarascon. Guillaume Breillac makes a good living at it. There’s even talk of building a funicular railway to take visitors up to the caves.’

‘A tourist destination.’

‘In a modest way. It doesn’t yet rival Lombrives or Niaux, but perhaps one day it will.’

Freddie looked towards the sunlit window and wondered, as he had not been able to stop himself doing many times in the past few years, what Fabrissa would say could she see the village come back to life again.

‘Certainly, the facts of the story are accurate,’ Saurat said. ‘In the beginning of the fourteenth century, the remaining Cathar communities were hunted down and eliminated. At Lombrives, more than five hundred were found by the soldiers of the Comte de Foix-Sabarthès, the future Henri IV, two hundred and fifty years after they had been entombed in the caves there.’

Freddie nodded. ‘I read of it.’

‘And those you met in the Ostal - Guillaume Marty, Na Azéma, the Maury sisters, Authier - all typical Cathar names of the period. Fabrissa also.’

‘Yes.’

Saurat hesitated. ‘Still, I am not certain what you think actually happened that night.’

Freddie held his gaze. ‘We are modern men, Saurat. We live in an age of science and rational thought. And even if it has not done us any good, we are not obliged to live, as our forebears did, under the oppressive and superstitious shadow of religion, of irrationality, of demons and retributive spirits. We know how psychology can account for night terrors, for hallucinations, for voices in the dark. We are aware of the tricks our minds can play on us, on our delicate, vulnerable, suggestible, shabby little minds.’ He shrugged. ‘I lose count of how many times I was told that when I was ill.’

‘You are saying the doctors are right?’

Freddie smiled. ‘They may be right, Saurat, but I know she was there. Fabrissa was there. I saw her. I talked to her, I held her in my arms. While I was in Nulle, tramping the grieving land that surrounded the village, she was as real to me as you are sitting here.’

‘And now?’

At first, Freddie did not answer. ‘There are moments of intense emotion - love, death, grief - where we may slip between the cracks. Then, I believe that time can stretch or contract or collide in ways science cannot account for. Perhaps this is what happened when I smashed the car and knocked myself out, perhaps not.’ He shrugged. ‘That such a person as Fabrissa once lived in the village of Nulle, I do not doubt. That somehow she sought me out, I also do not doubt.’

‘Faith, then?’ said Saurat, looking around at the book-lined shelves. ‘A belief in something more than this?’

‘Who’s to say? Life is not, as we are taught, a matter of seeking answers, but rather learning which are the questions we should ask.’

Saurat looked down at the antique letter, at the words he had so painstakingly translated for his English visitor.

‘Why did you wait so long?’

‘I needed to be ready to hear it.’

‘Ah.’

‘And to make an end of things.’

Saurat put his glasses down on the table and rubbed his eyes.

‘Perhaps also, because you knew what it would say? I had the impression nothing in it surprised you.’

Freddie shrugged again. ‘“We are who we are, because of those we choose to love and because of those who love us.” That’s what Fabrissa wrote.’ He smiled. ‘One does not need a translator to understand the truth of those words.’

Both men fell silent. Inside the bookshop, the clock continued to mark the passing of the day. In the street outside, the burst of a car horn, a woman calling to a child or a lover in an affectionate voice, the sounds of the modern city on an afternoon in spring.

‘What do you intend to do with the letter?’ Saurat asked after a while.

‘Nothing.’

‘I’d give you a fair price.’

Freddie laughed. ‘I don’t think it’s possible to put a price on such a thing. Do you?’

‘Perhaps not,’ Saurat conceded. ‘But if you should ever change your mind . . . ’

‘Of course, I’ll bear you in mind.’

Freddie stood up. He put on his overcoat, slipped the letter into the pasteboard wallet.

‘You’ll allow me to pay you for your time?’

Saurat held up his hands. ‘The pleasure was mine.’

Freddie pulled out a fifty-franc note all the same and laid it on the counter.

‘To donate to a good cause, then,’ he said.

Saurat acknowledged the gift with a nod. He did not pick it up, but neither did he attempt to give it back.

At the door, the two men shook hands, on the afternoon, on the story, on the secret they now shared.

‘And what of your brother?’ Saurat said. ‘In your travels, your work for the War Graves Commission, did you ever find the answer to the question you were seeking? Did you find out what happened to him?’

Freddie put on his trilby and slipped his hands into his fawn gloves. ‘He is known unto God,’ he said. ‘That is enough.’

Then he turned and walked back up the rue des Pénitents Gris, his shadow striding before him.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to all those who have worked so hard on

The Winter Ghosts

.

The Winter Ghosts

.

My agent, Mark Lucas, continues to be an inspiration, a wonderful editor, and makes it fun despite the absence of Post-it notes! To Mark, Alice Saunders, and everyone at LAW, thank you.

At Orion, a huge thank you to everyone in the editorial, publicity, marketing, sales and art departments, especially the editorial dream-team of Jon Wood and Genevieve Pegg, as well as Malcolm Edwards, Lisa Milton, Susan Lamb, Jo Carpenter, Lucie Stericker, Mark Rusher, Gaby Young and Helen Ewing; and to Brian Gallagher for the beautiful illustrations.

I would not have finished the book without the affection and practical help of family and friends, especially my mother-in-law, Rosie Turner; my parents, Richard and Barbara Mosse; fellow dog-walkers, Cath O’Hanlon, Patrick O’Hanlon and Julie Pembery and my sister, Caroline Matthews; Amanda Ross, Jon Evans, Lucinda Montefiore, Tessa Ross, Robert Dye, Maria Rejt, Peter Clayton, Rachel Holmes, Bob Pulley and Mari Pulley.

Finally, without the love and support of my husband Greg Mosse, and our children Martha and Felix, none of this would matter. It is to them, as always, that the book is dedicated.

Author’s Note

Other books

Pieces in Chance by Juli Valenti

DW01 Dragonspawn by Mark Acres

Brave Enough by M. Leighton

Packing Heat by Kele Moon

Brick (Double Dippin') by Hobbs, Allison

Tales of the Dying Earth by Jack Vance

Holy Shift! by Holden, Robert