The Wish Giver (6 page)

Authors: Bill Brittain

“N

o rain for three weeks. Well’s gone dry, and the cistern’s near empty. Tomorrow after school, you’d best haul the tubs down to Spider Crick and fill ’em up.”

Those were the first words Adam Fiske’s pa said to him on Sunday morning. They made Adam angry.

Yesterday’s Church Social had been fun, and Adam had stayed late. When he’d gotten home, he’d hung his pants in the closet, with the red-spotted card still in the pocket, and gotten right into bed. He had woken on Sunday morning with all the fun still fresh in his mind.

Now Pa had to ruin it all.

“Do I have to?” Adam complained. “Everybody laughs at me when I drive the wagon through town. And filling all those tubs from the crick

takes forever. They sure do hold a lot of water.”

“Well, doesn’t seem like much by the time you get home,” Adam’s ma put in. “What with drinking and cooking and washing and water for the animals and trying to keep the crops from burning, it’s gone in no time. Until it rains, you’ll probably be hauling every day, Adam. Get used to it.”

“It don’t seem fair,” Adam grumbled. “This is the only farm in Coven Tree where the well goes dry if it doesn’t rain regular every three days. Besides, what would be the harm in getting water from the spring on Mr. Jenks’s farm? What he doesn’t use just soaks back underground. That way I wouldn’t have to go through town and—”

“That’s enough, Adam!” Pa snapped. “This is our farm, and we’ll run it without asking charity from anybody. We’ll take our water from Spider Crick, and you’ll haul all that’s necessary.”

Well, there it was. Pa’d saved for a Long time to buy this land, and he’d built the house and barn with his own hands. His stubborn pride refused to allow him to become beholden to any man.

“Oh, cheer up, Adam,” Pa went on. “Tomorrow

Uncle Poot will be here. We’ll find water yet.”

“Uncle Poot?” said Adam. “The dowser man?”

“Yep. He doesn’t get down to this end of the valley much, but I asked him special, and he agreed. That forked stick of his never makes a mistake. Dig a well where a dowser man’s stick points, and you’ll soon strike water.”

“Maybe,” said Adam doubtfully. He couldn’t believe that dowsing really worked. Most likely he’d be hauling water from Spider Crick for the rest of his life.

After breakfast the next morning Adam set out for school. On the way he met Polly Kemp on the road. “Good morning, Polly,” he called as he caught up to her. “After today I’ve got a few days off before final tests start. What do you think of that?”

“

JUG-A-RUM!

”

Well, if that wasn’t just like Polly! Making strange noises instead of giving a civil answer, “You don’t have to get sassy with me, Polly Kemp,” Adam said crossly.

“

JUG-A-RUM!

”

She was rude, to be sure. But it did beat all, how much Polly sounded like a real frog. He

told her so, hoping she’d be pleased.

“

JUG-A-RUM!

”

After a final remark, Adam trotted on.

At school he sat right behind Rowena Jervis in science class. Rowena was usually a good student. But not today. Her mind seemed a million miles away. She kept sniffling and sighing and murmuring something about…well, “feet stuck” was what it sounded like. But maybe he’d just heard wrong.

When Adam got home from school, he harnessed Hank and Herb, their two horses, to the big flat wagon. He loaded the eight huge iron tubs onto the wagon bed and climbed up to the seat. “Giddap,” he ordered with a flick of the reins.

Off they went, with the tubs in back clanking loud enough to drown out the clopping of the horses’ hoofs.

At the edge of town the hooting began. “Here comes ol’ Adam Fiske with his water-draggin’ wagon!” yelled Orville Hopper.

“I guess they’re getting mighty thirsty out there!” jeered somebody from inside the fire-house.

He passed Agatha Benthorn and Eunice Inger

soll on their way home from school. The two girls made faces and stuck their noses in the air. Adam about died of embarrassment.

Once through town and down by the crick, Adam pulled the wagon as close to the water as he could get. He took off his shoes and socks, and rolled up his pant legs. Then he took a bucket from under the wagon seat and climbed down to the ground.

He waded into the icy water of the crick and scooped up a bucketful. Then he walked to the wagon, with the sharp stones cutting at his bare feet, and poured the water into one of the tubs. The whole bucketful seemed scarcely to cover the tub’s bottom.

Scoop…pour…scoop…pour…scoop…pour…Time after time Adam lifted buckets of water, until his shoulders felt as if they were being pierced by a white-hot iron bar. By the time all the tubs were filled, the sweat was dripping from his chin, and his feet were almost numb from the cold crick water.

Then there was the return trip to make. Again there were jokes and catcalls from the villagers; and then, just as he approached the farm, one wagon wheel hit a rock, jarring the filled tubs.

Water sloshed loudly onto the wagon bed and then poured down into the dirt. Where once the tubs had been full to the top, now they were almost a third empty. One third of Adam’s work, soaking into the dry earth.

“Consarn!” he muttered angrily.

Pa was in the front yard, pacing back and forth next to a white-haired little man who was slender as a reed and looked to be a hundred years old. In each palm-up fist, the old man gripped one prong of a forked applewood branch some three feet long. His eyes were glued to the spot where the prongs met and formed a kind of pointer that shook slightly as he walked.

“Stop and give the horses a rest, Adam,” said Pa as the wagon rolled up beside him. “Come and meet Uncle Poot.”

“Durnedest thing I ever seen,” Uncle Poot muttered as Adam climbed down from the wagon. “Seems like there should be water under this land. But I’ve covered every inch, and the rod didn’t twitch once.”

Adam looked curiously at the branch in Uncle Poot’s hands. “It don’t seem possible,” Adam said, “to find water under the ground with just an old stick.”

“It ain’t hard,” Uncle Poot replied. “For those of us who have the gift.”

“The gift?”

“The dowsing gift, boy. Only one person in a thousand—mebbe

two

thousand—has it, the way I do. Without the gift, a man could tote this stick over the whole state of Maine and never know when there was water right under his feet.

“But you can find the water, huh?”

“Dang tootin’ I can! When I walk over an underground stream holding the prongs of my dowsing rod, t’other end of it will twist down and point to water like a fish pole when a trout hits the lure.”

“Are you ever wrong?” asked Adam. “Does the stick ever point when there isn’t any water?”

“Never,” said Uncle Poot. “Why, didn’t I dowse Luke Jenks a well right in his backyard after he’d sunk four dry holes looking for water? Ten feet down in the spot I pointed was water enough for him, and the neighbors on either side as well. And Dan’l Pitt had near given up finding water, but I dowsed it for him.”

Then the old man shrugged. “But there’s got to be water there for me to find it. And there’s none under this farm. Sorry, Mr. Fiske.”

“It ain’t your fault, Uncle Poot,” said Pa with a sigh.

The dowser man started to walk off. But Adam had an idea.

“Uncle Poot,” he said, “could I have that dowsing rod?”

“This old stick?” Uncle Poot held the branch out to Adam. “Take it and welcome. I can cut me another anytime. But don’t expect it to find water for you. The power’s not in the dowsing rod, but in the person holding it.”

“Maybe I have the dowsing gift, Uncle Poot.”

“Mebbe,” the dowser man replied doubtfully. “But it ain’t likely. The gift’s a rare thing.”

With that, Uncle Poot shuffled off down the path. Adam grasped the prongs of the branch and slowly walked the length of the yard. The stick bobbed slightly at each step, but never did it twist and point to the ground the way the dowser man had described.

“Face it, Adam,” said Pa. “We’ll be hauling water until it rains.”

At supper that evening, Ma brought up something that had been on her mind for some time. “I’d like to grow flowers outside the kitchen win

dow,” she said. “They’d be pleasant to look at.”

“Flowers need a heap of water,” said Pa. “How ’bout it, Adam? You’d be the one doing the hauling.”

At first Adam felt like saying no. But one extra trip a week to the crick wasn’t much more than he was doing already. And if it’d make Ma happy…

“Flowers would be kind of pretty out there,” he said. “What kind were you thinking of, Ma?”

“Some morning glories and a rosebush or two,” she said. “And maybe you could make a fence, Adam. For the flowers to climb on.”

“Now hold on,” said Adam in mock sternness. “Flowers are one thing, but a fence is another. Especially if I’ve got to make it.”

“Well, if you don’t think…”

“I was just joshing you, Ma,” said Adam with a chuckle. “I’ll make your fence, first thing tomorrow. It won’t take any time at all.”

By the time the chores were done after supper, Adam was bone tired. He went to bed early. But his shoulders ached from scooping water, and he just couldn’t fall asleep. He punched his pillow angrily. He and Ma and Pa worked hard

on the farm. It was a shame they could barely scratch out a living. All because they had no water!

He tossed and turned in bed, staring first at the little table in the corner and then out the open window, where the full moon was just clearing the horizon, and finally at the open door of his closet.

A ray of moonlight came through the window, and the closet door seemed to glow in the dark. There, hanging on a hook, were the pants he’d worn to the Church Social yesterday.

The Church Social—Thaddeus Blinn. What had the sign said?

I can give you whatever you ask for

.

“I don’t think you can deliver on this one, Mr. Thaddeus Blinn,” Adam whispered into the still air. “But where’s the harm in trying?”

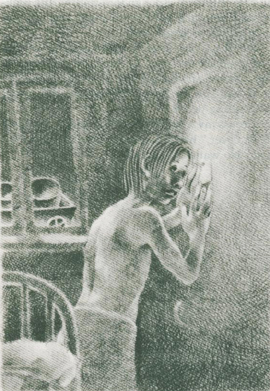

He got out of bed, Walked barefoot to the closet, and searched through the pants pockets. There, all crumpled and wrinkled, was the card with the red spot. Smoothing it as best he could against the back of the door, Adam pressed his thumb against the spot.

“I wish…” he began. “I wish we had water

all over this farm. Enough for washing and cooking and drinking and for the crops, and…and with plenty to spare, too!”

He felt his thumb grow warm against the spot and dropped the card to the floor. He went to the window and looked out. Everything seemed as it had always been. He listened. No sound of gurgling water.

“I guess my wish is too much even for the great Wish Giver,” he said glumly as he got back into bed. “No water. Tarnation!”

W

hen Adam woke up Tuesday morning, his first thought was that he didn’t have to go to school until the end of the week, when tests began.

Then he remembered the wish he’d made last night. He dressed quickly, gulped his breakfast, and rushed outside to see if maybe…

The sun hung in the sky like a big shiny brass disc, and the yard around the house was cracked and dusty from lack of water. “I guess my wish ain’t going to come true,” he murmured to himself.

“What wish, Adam?” There was Ma, back from the barn with an empty feed dish in her hand.

“Nothing, Ma. Now where was it you wanted your fence set up?” Adam was flustered that

Ma’d heard his talk about wishing. He was too old for such nonsense.

“Just here under the window,” Ma replied. “No, the house will shade it from the afternoon sun. Perhaps there by…or maybe off to the side where it can be seen from the porch…. Then again, it could go…oh, I don’t know, Adam. Where do you think it should go?”

Adam grinned and shook his head. It did beat all, the trouble Ma had making up her mind when she was doing something to please herself. She could spend an hour just deciding whether to pay a visit to her neighbor, Mrs. Jenks, and when it came to choosing fabric for a new dress, she’d stand in Stew Meat’s store all morning, sorting through the bolts of cloth until she found one that was exactly right.

But running the farm was another thing altogether. “Edward, you get the horses to the blacksmith before you do another thing,” she’d tell Pa, like a general giving orders. Or, “Adam, the beans need cultivating. Right now!” And Pa and Adam would obey, figuring Ma was. seldom wrong about when farm work had to get done.

Adam knew how to get Ma to make up her mind. “Why don’t you put the fence over there?”

he said, pointing to the one spot that didn’t get any sun all day long.

“Oh, you men!” Ma answered. “Any fool can see the best spot is there on the corner, where we can see the flowers from two sides of the house. That’ll do nicely.” She picked up Uncle Poot’s dowsing rod from where Adam had dropped it and scratched a line in the dusty earth.

Adam paced the length of the line. He calculated that five fence posts would do, and he scuffed the dirt with his heel at the places he’d dig them.

He made the five holes with a spade. Each hole was about two feet deep. “You’re making too much work for yourself, Adam,” Ma told him. “Are you trying to go all the way down to China?”

“I want them posts to stay put,” Adam said. “Not blowing over in the first strong wind.” The earth at the bottom of each hole was as dry as that on the surface. If the whole farm was like that, it’d be a bad year for the crops unless they got watered soon. He’d have to make another trip to Spider Crick after lunch.

Adam leaned on the spade, resting. He looked about the dusty yard and down toward the hol

low where the barn was. Then his eyes lit on the dowsing rod.

He picked it up. Just a thin, two-pronged branch of applewood, he thought. How had Uncle Poot held it?

He bent his arms at the elbows and gripped a prong in each upturned palm. The small stub of wood at the crotch stuck out ahead as if pointing the way to go. Adam took one step. Another.

Suddenly the prongs started twisting and turning in Adam’s hands like live things. The pointer jerked straight down, and the branch’s bark wrinkled and split as the dowsing rod bent into an arc.

Adam tried yanking up against whatever force was pulling on the stick. It was impossible. The stick had a life of its own, and it insisted on pointing to the soil at Adam’s feet.

Adam loosed his grip on the dowsing rod, and it dropped to the ground. There it lay, no longer curved, but just a forked stick from an ordinary apple tree. Adam was scared stiff.

Gingerly he picked up the dowsing rod. Hot as the day was, he could feel cold sweat on his forehead. He walked to the other end of the yard.

Again he grasped the two prongs of the stick, just as he’d seen Uncle Poot do it. He took a single step forward.

Once more the pointer jerked toward the ground, almost as if an invisible hand had reached out of the earth and pulled at it. Adam could feel the skin on his hands being rubbed raw. With a mighty effort he hurled the stick from him, watching it turn into a lifeless bit of wood in midair.

Uncle Poot’s words popped into Adam’s head: “When I walk over an underground stream holding the prongs of my dowsing rod, t’other end of it will twist down and point to water like a fish pole when a trout hits the lure.”

Adam gasped. He had the dowsing gift himself! Or did he?

The yard all about him was as dry and parched as it had ever been. There couldn’t be water under there.

So what had caused the dowsing rod to jerk and point? He decided to try again.

The branch began to twist in his hands as soon as he took his first step with it. He crisscrossed the yard several times. Wherever he went, the

stick yanked itself toward the ground like a pointing finger.

“Ma!” Adam dropped the rod and ran pell-mell toward the house. “Ma!”

Mrs. Fiske came to the kitchen door. “What are you howling about, Adam?” she asked. “Are you hurt or something?”

“I think I found water, Ma,” Adam crowed. “Water under the whole yard. The dowsing rod points down wherever I go.”

“Then why didn’t Uncle Poot find it yesterday?” Ma replied with a snort. “All the water on this farm wouldn’t give a cricket a good drink. Get inside and put the plates out, Adam. Pa’ll be here directly, and he’ll be hungry.”

“But Ma…only water could make the rod bend the way it did,” said Adam. “Uncle Poot said so.”

“You’re talking nonsense, Adam. I think the heat’s got to you. Go in the parlor and rest. I’ll get things ready here.”

“But…”

“That’s enough. Do as I say.”

Adam plodded into the parlor. He wondered how he could get Ma to—

POP

He heard a sound like somebody’d taken a huge cork out of a gigantic bottle. Then there was another sound, this one a wet, liquid hissing.

FSSSHHHHH

Adam heard the sounds a second time.

POP FSSSHHHHH

And a third! A fourth! A fifth!

POP FSSSHHHHH

POP FSSSHHHHH

POP FSSSHHHHH

Before he even had time to wonder what had caused the strange noises, his mother called Loudly. “Adam! Close the windows in there! Heaven be praised, it’s starting to rain!”

Through the parlor window, Adam saw the parched yard and the clear blue sky and the fiery ball that was the sun. “It sure ain’t raining on this side of the house!” he yelled back.

He still heard the hissing.

FSSSHHHHH

“Adam, come help me! The curtains are getting soaked!”

He ran to the kitchen. Large drops of water were spattering in through the open window over the sink, and he could hear water drum

ming onto the roof and gurgling through the gutter pipes on its way to the big cistern in the cellar.

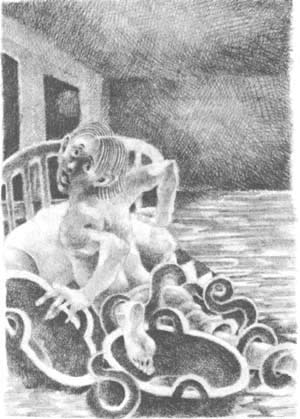

Adam dashed out onto the back porch. He couldn’t believe what he saw!

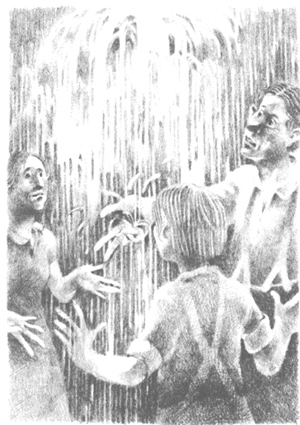

From each of the fence post holes he’d dug, water was gushing forth as if spewed from a fire hose. Up. Up. Higher than the house the silvery liquid spouted, forming five columns that glittered as the sunlight caught them. At the top of each column the water spread out in all directions, so that there appeared to be five watery umbrellas at the corner of the house.

“Water!” Adam cried as he ran under the falling drops. There he stood, getting soaked to the skin and laughing out loud. “Water!”

There was an awed gasp from behind him. Adam turned about.

Pa was gazing at the spouts with wonder in his eyes. Then Ma rushed out of the kitchen. “Never in my life have I seen it rain as hard as—”

She caught sight of the five spurting columns and fell silent, her mouth gaping.

“It’s real water,” said Pa over the sound of the hissing spouts. “Out there in the cornfield, I

thought I was going soft in the head.”

“What happened in the cornfield, Edward?” Ma asked.

“I jabbed a hoe in the ground,” Pa replied, “and water started coming out of it. Not just running along the ground, but shooting right up in the air. Like those spouts, but nowhere near as big. I thought I was addled from too much sun or else coming down sick. Anyhow, I poked another hole, and water came up out of

that

one, too. In all my life I never saw the like of it. It can’t be happening. It just can’t be….”

“But it is!” cried Adam. “We finally got water on this here farm.”

“It’s more’n a little strange,” said Pa. “Still, it’d be a shame not to use what’s been provided. I plan on jabbing more holes, so’s I can water all the crops. Adam, tote the tubs up here and fill ’em. No telling how long the water will keep spouting.”

But the water didn’t stop. By the middle of the afternoon all the crops had been given a good drink, and every tub and pot and kettle on the place was filled with water. Runoff from the gutters had filled the big iron cistern in the cellar, and Adam had to unhook the pipe that led inside

so the water could run off into the yard.

At bedtime that evening the water was still gushing forth as strong as ever. It hissed from the five holes and pattered loudly on the roof. “I hope that noise won’t keep us awake,” said Ma.

“The sound of that water is better’n the sweetest music I ever heard,” said Pa. “I plan on sleeping like a log tonight.”

Adam smiled a sleepy smile as he lay on his bed that night. Water—gurgling in the gutters and spattering to the ground and making the plants grow. No more hauling the tubs down to Spider Crick and filling ’em up and hauling ’em back again. Everything seemed just about as perfect as it could be.

With a contented sigh, he fell asleep.