The Woman Who Died a Lot: A Thursday Next Novel (9 page)

Read The Woman Who Died a Lot: A Thursday Next Novel Online

Authors: Jasper Fforde

“I might have,” I replied, “but that was completely different.”

“How was it completely different?”

“Mostly because Flossie Buxton dared me to. She was more into that sort of thing. Still is, actually. And . . .”

“And what?”

“I charged a pound.”

“Holy strumpets,” said Tuesday, making a quick mental calculation. “That’s the equivalent of—let’s see—over twenty-two pounds seventy-five pence in today’s money. Did you ever consider a career as a stripper? It was going pretty well for you.”

“No I didn’t, and yes, I know what we said, but please, no more flashing. It’s . . .

undignified.

”

I was actually relieved that she was taking the social side of being a sixteen-year-old seriously. She might be a supergenius, but we wanted her to be a real person, too—even if that meant her being a bit grumpy, sometimes uncommunicative and on occasion demonstrating ill judgment with boys.

“Okay, no more flashing,” she said.

“And

especially

not to Gavin Watkins.”

“I think he’s cute.”

“Cute? He’s a foulmouthed little creep.”

Tuesday giggled. She was pulling my leg. “No flashing, promise,” she said. “Boy, your face!”

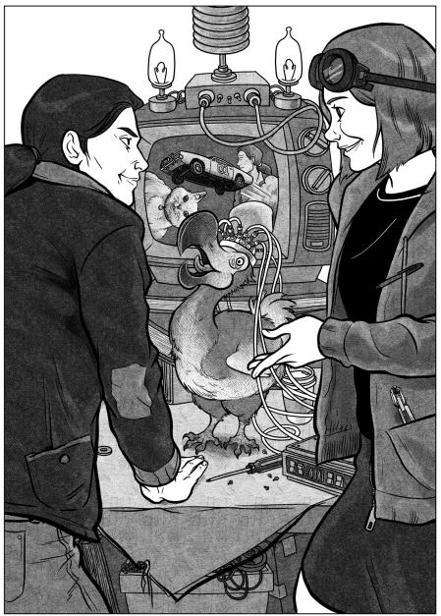

“Very funny,” I said. “What are you doing to Pickers?”

I had turned my attention to her workbench, and in particular to our pet dodo, Pickwick, whom I had personally sequenced almost twenty-six years before, when the home-cloning fad was in full spate. She was a valuable V1.2—without wings, as all the early ones were—and unique in that she was not just the oldest dodo in existence but also sequenced before the mandatory autosenescence laws were brought in. Barring a major extinction event and the cat next door, she would outlive everything.

“Ah, yes,” said Tuesday, turning to stare at Pickwick, who was sitting patiently on the workbench. She was wearing a small, bronze domed cap on her head that was about the size of half a tennis ball, from which trailed a jumble of brightly colored wires.

“After rejiggling her DNA until her feathers grew back, I got to wondering in what other ways she might be improved.”

“I’m not sure Pickwick needs improving,” I said somewhat dubiously, since Pickwick had been with me for so long it was almost impossible to recall a time when she wasn’t wandering around the house, plocking randomly and bumping into furniture. “I’d miss her glorious pointlessness if it were taken away.”

“Okay, well, maybe,” said Tuesday, “but I found that reengineered dodo brains have neural pathways that are particularly easy to map. That copper helmet thingy she’s wearing is an avian encephalograph. By reading the electrical brain activity, I’m attempting to discover what’s going on in her head.”

“I’m not sure you’ll find very much,” I said, since despite my affection for the small bird, I was under no illusion about the level of her intelligence.

“In that you might be mistaken,” said Tuesday, “for with my newly invented Encephalovision I can decode and then visualize her brain patterns. Watch.”

Tuesday turned on a highly modified TV, tuned it in carefully, and after a while strange shapes flickered and danced on the screen.

“What we’re looking at,” said Tuesday with a grin, “is what Pickwick is actually

thinking.

”

I tried to make some sense of the shapes on the screen.

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing to one of them.

“Either a small ottoman or a large marshmallow,” said Tuesday. “That blurry thing down there is the cat next door, this is a supper dish, that’s you and me, and that folder in the corner is all her system files. I’m not sure, but I think she’s running on software modified from a program that used to run domestic appliances. Washing machines, toasters, food mixers and so forth.”

“That might explain why she caused such a fuss when we got rid of the old Hoovermatic. What do you think that is?” I pointed to an image on the screen that looked like a large red car leaping through the air.

“I think it’s an episode of

The Dukes of Hazzard.

”

“She used to like watching that,” I said. “Never thought it went in, though. Just a simple question: Is there any useful purpose in knowing what a dodo is thinking?”

“Not at all. It’s simply part of wider research on a neural expansifier that increases the synaptic pathways in the brain. Aside from repairing traumatic damage and reversing the effects of dementia, it can potentially make dumb people smart.”

“I’m trying hard, but I’m not sure I can think of a more useful invention.”

“Me neither—but it’s a long way from testing on humans. This is just a crude device to test proof of concept. This afternoon I successfully increased Pickwick’s intelligence by a factor of a hundred.”

This was astonishing indeed. I stared at Pickwick, whose small black eyes stared back at me, and she cocked her head to one side.

“Hello, Pickwick,” I said.

“Plock,” said Pickwick. I took a marshmallow from my pocket, showed it to the dodo, hid it in my left palm in full view and then displayed both fists to her.

“Where’s the marshmallow?”

Pickwick stared at both my hands, then at me, then at Tuesday. She blinked twice and scratched the side of her head with her claw.

“Hm,” I said, “she doesn’t seem much different to me.”

“I admit it’s not a blazing success,” agreed Tuesday, “but I think the problem lies in Pickwick. Because her intelligence is on a par with a dishwasher’s, making her brain a hundred the times the size creates no appreciable difference. D’you think I should have made it a

thousand

times smarter than it was?”

“I think you should leave her alone. Having almost no brain doesn’t seem to have stopped her enjoying a long and successful life.”

“I suppose so,” agreed Tuesday, switching off the machine.

“How’s the keynote speech for MadCon on Thursday?”

“Going pretty well,” she replied, patting a pile of much-corrected papers that were lying on the desk next to her. “I’m just not sure whether I should open directly with my algorithm that can predict the movement of hyperactive cats, discuss the possibilities of Encephalovision Entertainment System— where we beam the thoughts of vain idiots straight into the nation’s homes— or go straight to the Madeupion Field Theory, by which I hope to power up the Anti-Smite Shields.”

I thought for a moment. Although I didn’t have a clue

how

her ideas worked, I knew what they did—kind of—and could understand their importance.

“The work on predicting the chaotic was your breakout paper,” I said, “so you should allude to that, I think. I’m not sure about the Anti-Smite device. After all, we’ve yet to see it work. What about your pioneering work on finding a way by which people can tickle themselves? That was pretty groundbreaking.”

“You’re right,” she said, “it still needs work, but once self-tickling is possible, the home-entertainment and psychotherapy industries can take a running jump. I’ve already had a call from Cosmos Pictures asking if I wouldn’t consider dropping the research in exchange for a signed picture of Buck Stallion and a walk-on part in

Bonzo—the Movie

.”

“Meeting Bonzo could be cool,” I said, as the long-running TV series was very much a cultural icon, “but to be honest, being asked to do the keynote speech at MadCon is probably more about saying a few jokes and getting the delegates in a good mood than delivering a doctoral thesis.”

“You’re right. I could do the joke about the three paradigm shifts at the races. That always brings the house down. Will Dad come?”

“He won’t miss it for the world, although one of us should stay back to keep an eye on Jenny.”

“The Wingco can look after her,” replied Tuesday. “They get on very well together. You know how he likes to talk about the power of the imagination and how it has the potential to make things real.”

“Only too well,” I replied. “Dinner at seven, Sweetpea.”

8.

Monday: Friday

The danger from Asteroid HR-6984 was first noted in 1855, when calculations showed this to be the same asteroid that was observed in both 1793 and 1731 and was missing the earth by the astronomical equivalent of a coat of paint every sixty-two years. Observations during the last flyby in 1979 proved what scientists had already feared: that the Isle of Wight–size lump of debris was traveling at over forty-two thousand miles per hour and would one day strike earth. The question of whether it would or not in 2041 was calculated by the International Asteroid Risk Likelihood Calculation Committee to be “around 34 percent.”

Dr. S. A. Orbiter,

The Earthcrossers

"I

spoke to Braxton Hicks today,” I said as Friday and I went into the dining room to set the table. “He tells me his daughter, Imogen, is looking for a ‘steady hand on the tiller.’ I said I’d mention it to you.”

“I don’t need my mother to set me up on dates,” he retorted.

“Besides, Mimi is totally bonkers. She surfed on the roof of a speeding car between junctions thirteen and fourteen of the M4. How insane do you have to be to do something like that? If she’d slipped, she’d have killed herself instantly.”

“You need a careful driver and soft-soled shoes,” I replied thoughtfully.

Friday looked at me with horror. “You didn’t?”

“I did. The flush of youth.”

“Does Dad know about this?”

“I think he was driving.”

“For God’s sake, Mother,” he said in an exasperated tone, “is there nothing dumb, daft or dangerous that you haven’t tried at some point?”

I thought for a moment. “I’ve never tried oysters. They can be quite dangerous.’

Friday shook his head sadly. To most of his and Tuesday’s friends, I was considered about the coolest parent one could have, but to Tuesday and Friday I was simply embarrassing.

“So . . . how many are we for supper?” he asked, counting out the cutlery.

“Joffy and Miles are in town and want to speak to your sister about the defense shield. All of us, of course, but maybe not Polly or Gran. Granddad will be coming.”

“Do you think he will want to talk endlessly about the good old never-happened days at the ChronoGuard?”

“Probably. Try to steer him onto plumbing. Which reminds me, Jimmy-G and Shazza both wanted to be remembered to you. Shazza said, ‘It would have been

seriously

good.’ And she raised her eyebrows in that sort of way when she said ‘seriously.’”

“Sharon ‘Steggo’ deWitt,” he murmured with a smile. “She would have been known as the ‘Scourge of the Upper Jurassic.’”

“Curiosity insists that I inquire why.”

“It was a popular place for timejackers to hang out. The Epochal Badlands, we would have called them. A jump into the Upper Jurassic was usually a safe escape. Not for deWitt. Twenty million years, and she knew each hour like the back of her hand. She was the one who tracked down ‘Fingers’ Lomax, hiding out after the Helium Heist of ’09. Or at least she would have.”

“She said you were going to have a weekend retreat in the Late Pleistocene.”

“I was going to have a lot of things. She and I would have been very close, so I got some of her potential future in my own Letter of Destiny. How will she turn out now?”

“Not great,” I replied, handing him the forks. “Two unremarkable kids, a husband she doesn’t like—and then she gets hit by a car in 2041.”

“Same year as me,” mused Friday.

I stopped folding the napkins. “You never told me you only make it to fifty-five.”

“Bummer, isn’t it?” said Friday with a shrug. “Thirty-seven years to go and counting.”

I stared at him for a while and felt a heavy feeling of grief in my heart. It was over three decades away, so I didn’t feel the

loss

quite yet, just the notion that I was going to outlive him. And that wasn’t how it was meant to happen.

“But there’s an upside,” he added.

“There is?”

“Sure. I miss HR-6984 slamming into the earth by three days.”

“That might not happen.”

“I’ll never know whether it does or it doesn’t.”

“What else happens to you?”

“My future’s my own, Mum.”

“Okay, okay,” I said quickly, since we’d covered this ground before, “forget I asked. Have you thought any more about university or a career?”

“No.”

I pondered for a moment.

“You know, your sister needs a lab assistant she can trust,” I said, “and she’ll pay you well. There’s a career there ready and waiting.”

“Mum, Tuesday’s work is Tuesday’s work. My life lies along a different path. I was going to be important—I was going to do wonderful things. I would have been head of the ChronoGuard and saved an aggregate seventy-six billion lives. Shazza and I would have made love on the veranda of my place in the Pleistocene while the mastodons bellowed at one another across the valley. I would have been there at Mahatma Winston Smith Al-Wazeed’s historic speech to the citizens of the world state at Europolis in 3419, and listened to his last words as he lay dying in my arms, and then implemented them. But now I don’t. All gone. Not going to happen. Mum,

I don’t have any function.

No kids, no wife, no achievements, nothing. I die aged fifty-five, my life essentially . . . wasted.”