Read The Woman Who Fell from the Sky Online

Authors: Jennifer Steil

The Woman Who Fell from the Sky (49 page)

“You’re not losing me. You aren’t losing us. It’s only for a short while….” But it was hard to be consoling when I was crying too.

“I thought Theadora was going to learn to walk in Yemen. I wanted her to see Soqotra. I wanted us to go camping together, to have pictures of her here. There is so much I wanted to do here with you.”

“I wanted to take her to Shahara with us and walk over the bridge. I wanted her to meet Zuhra’s baby. I’ll never see Zuhra again,” I said. I hadn’t been able to see Zuhra since Theadora was born because she had typhoid. She was also pregnant, due in less than a month. Now she would never meet Theadora, and I would never meet her little boy.

We also worried about our staff. Every morning when I carried Theadora downstairs, Negisti hurried to take her from me. Emebet, Rahel, and the rest of the household staff also adored cheery little Theadora. The enormous, echoing residence felt cozier and more of a home with her in it.

When Tim and I sat down with the residence staff to explain about the evacuation, Negisti pulled her apron over her face and wept. Emebet and Salaam were also in tears. We couldn’t think of anything to say to comfort them.

On our last morning in our house, I gave photos of Theadora to each of the staff and taped more pictures to the refrigerator. We took only two suitcases. Everything else we had to leave behind: all of Theadora’s books and toys, her bed, her changing table, her room. I didn’t mind leaving my own things behind, but I hated leaving behind everything Theadora knew as home.

When Tim came to take us to the car, the staff wouldn’t let go of us. I had to actually pry Theadora out of Rahel’s arms. Crying, I hurried to the armored car. And we were off, leaving behind the house that had been our home for three years, the only real home Theadora had ever known, and the country that had been my home for four.

This wasn’t how I planned to go. I wasn’t ready. There was so much of the country still left to explore. We had so many friends. And I was finally making progress in my Arabic lessons.

But I can’t say we didn’t make the most of our time. The years I spent living with Tim in Yemen were the happiest of my life. I moved in with him in the spring of 2008, though we had been spending every possible spare minute together for months before that. We were both working insanely hard at our respective careers, but we were both engaged in work we loved. I was writing this book and doing some freelance reporting, and Tim was working approximately eighteen hours a day as the British Ambassador to Yemen.

Nearly every day, Tim rose at six

A.M.

, and I got up with him so we could have breakfast together before he left for the office at seven-fifteen. Then I was free to swim, do yoga, and work for several hours before he reappeared in the evenings. As soon as I moved in, Tim created an office for me in the top floor of our house. I had a room of my own, a massive desk overlooking our garden and pool, and a mini-kitchen next door where I could make coffee and tea. Our upstairs refrigerator was fullof dried fruit, nuts, dark chocolate, champagne, and soy milk. It was paradise.

If there was time in between our workdays and dinner, we’d have a sherry or gin and tonic and sit on a kitchen counter swinging our legs and talking. Late at night we read plays or short stories out loud to each other. On weekends, we went for long hikes in nearby wadis or in the Haraz mountains.

Many of my reporters visited me, but Zuhra came most often. We’d have tea and sit talking in the parlor or my office. She wasn’t in the least bit awed by the grand house and made herself at home, even letting me know in advance what she’d like Emebet to make her for lunch.

I found I missed working with Yemeni reporters. So I was happy when Nadia al-Sakkaf asked me to come train some of her reporters at the

Yemen Times

, my former rival. It was almost exactly like my first training course at the

Yemen Observer

—the reporters had the same challenges and the same questions. But this time, I was much more relaxed and had a few more answers.

Adding to the luxury of my daily existence was the household staff. A household staff! I had never even hired a cleaning person before I moved to Yemen, and suddenly I lived in a house with a housekeeper, cook, cleaner, and gardener. I had no idea what to do with them. When Tim and I came down to breakfast in the morning, Negisti had already laid the table with fresh-squeezed orange juice, fresh fruit, muesli, and yogurt. As soon as we were seated she poured us fresh coffee. It was overwhelming and it made me shy.

For weeks I couldn’t bring myself to ask the staff to do anything. Emebet would ask what I wanted for lunch, and I would say, oh, I’ll make myself a sandwich, don’t worry. At night I’d sneak down to do my own laundry instead of putting it in my assigned hamper. But slowly it dawned on me that I was depriving our staff of the opportunity to do their jobs. This was the work they were paid to do. So I began to timidly suggest that if Emebet were not terribly busy, would she perhaps be able to make me a Thai salad with tofu?

Negisti, Emebet, and Alem quickly became family. I spent hours pouring over recipe books with Emebet, planning menus for diplomatic dinners, and asking her to experiment with vegetarian, whole-grain foods. I attended the wedding of my driver’s daughter with all three women. I spent more time talking with our staff than with almost anyone else in my life other than Tim. The birth of our daughter, Theadora, brought us all closer. “She has many mothers,” Negisti would say. And it was true. If I ever needed anyone to hold Theadora, settle her for a nap, or make her laugh, I had plenty of volunteers.

For years, I tried in vain to get the staff to call me Jennifer or Jenny instead of madam. They would smile in agreement, say “like family?,” and then keep calling me madam. Not until Theadora and I were evacuated, and Emebet began sending parcels of our favorite foods to me in Jordan (where we stayed until the end of Tim’s posting), did she write on the note taped to a box of muffins that they were for “Jeny and Teodora.”

Having a staff was only the beginning of how surreal my life became. Suddenly I was hosting dinner parties several times a week for Yemeni politicians, business people, hostage negotiators, other ambassadors, development workers, or visiting British ministers. Every official I met—and I met many!—treated me with respect and kindness and as though I were Tim’s wife. Divorce is common in Yemen and Yemenis (many of whom have more than one wife) were warm and understanding about our relationship.

There was hardly a night when we didn’t have official cocktails or dinner at the house or a National Day to attend elsewhere. Mostly, I loved this. I am a social person, and it was great fun to meet and talk with such a wide range of people—and to practice my Arabic. But I did occasionally worry I would get myself in trouble by talking too much or too freely. I once got into a debate with the foreign minister about the freedom of the Yemeni press. He had claimed, over the soup course, that the Yemeni media was unfettered. Having run a Yemeni newspaper, I knew differently and said so. No, the Yemeni press is free! He insisted. What was it that I couldn’t write about?

Well, for starters we couldn’t criticize the president by name, I said. And we couldn’t write that there was an argument against capital punishment. And we couldn’t write freely about religion. I went on.

Yes, yes, said the minister. But there are good reasons for those things!

I guess I just have a different definition of “free,” I said.

We both laughed.

THE MOST ASTONISHING THING

happened at a holiday party during my last year in Yemen. Faris, my former boss whose approval I had fruitlessly sought for the length of my tenure at the

Observer

, told Tim that the newspaper had never been better than it was under my leadership. Which was bittersweet news, as it made me wish I were still at the paper at the same time that it filled me with a warm sense of closure. It wasn’t long after this that Faris approached me at a party to ask if I would come by the office to talk with the new American woman running it. “If you could just give her some advice,” he said. “Just tell her what you did with the paper to get it the way it was.”

But the attack on Tim brought all of this to a premature end. We had to leave. After a family vacation in the United States, Theadora and I moved to Amman, to be as close to Yemen as possible. I rang the only person I knew in Jordan, my friend Saleh whom I’d met when he worked in Yemen. A week later, he had found me both a comfortable apartment and a babysitter. Tim visited us whenever he could, but he was extremely busy in the final few months of his posting. It was a hard, hot summer alone with a baby in an unfamiliar city.

Amman was a world apart from Sana’a. At the gym near my house, most women didn’t wear hijabs, and they all showed up in full makeup, carrying designer bags. Teens socialized at massive shopping malls. Alcohol was available everywhere. I found the conspicuous consumption overwhelming. I pined for Yemen.

Eventually, I settled into a social life with a few Jordanian friends and with other parents I met at the British Club and an American playgroup. By the time I discovered people with whom I really enjoyed spending time, it was time to move again. We left Jordan in October 2010, again taking a quick trip to the United States to see family before landing in the UK in November.

Tim, Theadora, and I are now happily ensconced in a (much smaller) new home in London. Though as I write, almost all of our belongings arestill in Yemen. Since the parcel bombs mailed from Yemen were intercepted, the UK has refused to accept air freight from Yemen. Including all of our worldly goods.

I miss Yemen every day. I miss its beauty, I miss the openness of the people, and I miss my former reporters, who write to me regularly on Face-book. Zuhra and I send each other long letters and photographs of our children. I still hope that someday it will be safe enough to take Theadora back there. I want her to see the country where her parents met and where she was first imagined.

Only occasionally do I read newspaper articles on Yemen. It’s pointless, as no one ever gets it right. No major newspaper has a full-time correspondent actually based in the country, so most stories are written by reporters parachuted into Sana’a for just a few days.

After running a newspaper in Yemen for a year, I was only just getting to grips with where to find information and which sources to trust. It’s not a country a reporter can figure out in a flying visit. So I don’t trust anything I read. The only way to stand a chance of knowing what is really going on in Yemen is to

be

there.

And even then the truth is elusive.

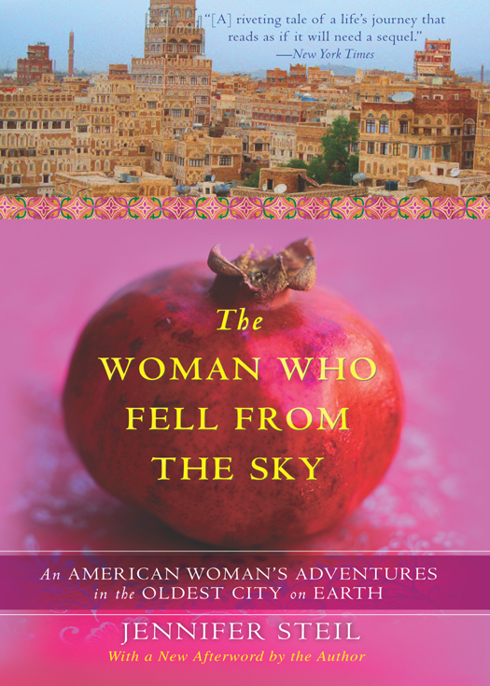

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JENNIFER F. STEIL

spent a year as editor of the

Yemen Observer

, a twice-weekly English-language newspaper published in Sana’a, Yemen. Before moving to Yemen in 2006, Steil was a senior editor at

The Week

, which she helped to launch in 2001. She has also worked as an editor at

Playgirl

and

Folio

and as a reporter at several newspapers. Her work has appeared in

Time, Life, Good Housekeeping

, and

Woman’s Day

. Steil has an MS in journalism from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College. She lives in London with her fiancé, Tim Torlot, and their daughter.

Other books

Lime Creek by Joe Henry

Lovers (9781609459192) by Arsand, Daniel; Curtis, Howard (TRN)

Exhale by Kendall Grey

Wild for the Girl by Ambrose, Starr

A Christmas Bride by Susan Mallery

TUN-HUANG by YASUSHI INOUE

Twice Dying by Neil McMahon

Northwoods Nightmare by Jon Sharpe

SinCityTryst by Kim Tiffany

Wedding Girl by Madeleine Wickham