The Work and the Glory (351 page)

First there were several sarcastic attacks on Joe Smith. In one place, Sharp challenged Joseph Smith to bring forth the gold plates so they could be retranslated by a local expert. Will shook his head in disgust. Did Sharp think that was an original idea? In another place, an article called the Prophet the “Presiding Great Devil” and the “Superior Ugly Devil.” It said that “Nauvoo” in “reformed Egyptian,” the language of the Book of Mormon plates, meant “a dwelling place for Devils, or where their evil deities delighted to dwell.”

Will hooted in open derision. This was like a spoiled child who, when he doesn’t get his way, reverts to petty name-calling.

He almost walked away then, thoroughly put off by the blatant bias. But then another article in the earliest posted edition caught his eye. Sharp had printed something from an Eastern newspaper, a piece that claimed to expose the real story of what had happened to the Saints in Missouri. As Will read the article—along with another of Sharp’s own editorials on

the same page—one of Sharp’s purposes became clear in Will’s mind. No doubt he intended, among other things, to convey the message that people in Illinois, and particularly Quincy, had been duped into extending food, housing, and sometimes even financial help to the Mormon exiles. While offering such aid was a noble thing, Sharp was suggesting it was misled.

Whoever had written the article for the Eastern paper claimed that his information came from an official U.S. report on the Missouri wars and was based on testimony of eyewitnesses. The only problem was, the ones interviewed were those who were enemies of the Church—members of the mob, generals who had directed the militia, the old settlers who had, Will knew, personally profited from the expulsion of the Saints from their farms. There were also several interviews with people Will knew were former Mormons who had turned against their own. Some of it was obviously downright fabrication.

One of the claims was so blatantly false that Will read it three times in total disbelief. Part of the tragedy was caused by Joseph Smith himself, it read. In a desperate attempt to win sympathy for his cause, Joseph had sent his own secret henchmen out to burn Mormon houses so the Saints would be enraged and rise up against the Missourians.

Almost before he knew it, Will was through the door and into the more subdued light of the newspaper office. He stopped, blinking a little to let his eyes adjust. There was a long counter that ran almost the full length of the room. Behind it, in the far corner, he could see the printing press. A movement to his right caught his eye and he turned. A man was at a table. In front of him, attached to the table, were cases that held thousands of pieces of type in tiny square dividers. Mounted on the wall directly in front of the man’s face were other cases; these held the capital letters. Peter had taken Will to show him a similar layout in the

Times and Seasons

offices and explained that this was where the terms “upper case” and “lower case” letters came from.

The man turned at the sound of the door opening and closing. He stood. Will saw that he was carrying the line of type he was working on in one hand. “Yes? May I help you?”

He was a big man, with biceps like a blacksmith’s—probably from pulling the press lever thousands upon thousands of times. His features were porcine, his eyes narrow slits in heavy cheeks.

“I want to speak to the editor,” Will barked, only now realizing where his anger had carried him.

The man set the line of type down carefully. He scowled darkly at Will across the counter. “Mr. Sharp is not here at the moment.”

“When will he return?”

“I’m not sure. Is there a problem?” It was not spoken with the slightest touch of cordiality.

“Yeah,” Will spat out. “I’ll tell you what the problem is.” He jerked a thumb in the direction of the window behind him. “Your paper is nothing but a pack of lies.”

The eyes narrowed even more. “You a Mormon?” he rumbled menacingly.

Will wasn’t cowed at all. You didn’t stay bosun on a sailing ship for long if you couldn’t hold your own with whatever kind of man had been hired as crew. “No,” he snapped right back, “I’m not a Mormon. Never have been. But I know enough about them to know that what you’ve got here is not news. It’s nothing but the most damnable lies.”

For a moment, there was nothing but the glittering dark eyes behind the rolls of flesh. Then the man jerked his head toward the door. “Mister, I suggest you just turn yourself around and get out of here. You don’t like what Mr. Sharp prints, don’t buy Mr. Sharp’s papers.”

“I didn’t buy one of these rags,” Will said evenly.

The man gave a short laugh of derision. And then, with open contempt, he turned his back on Will and returned to the typesetting table, sitting down heavily. “Then you got no cause for sniveling, do you?” he tossed over his shoulder.

For a moment, Will stood there, breathing deeply, his fists clenching and unclenching. Then he knew what to do. “Only one,” he responded. “I don’t like passing open garbage on my way to breakfast.” He spun around and walked to the window where the papers were pasted.

“Hey!” the man yelled as he saw Will’s hands go up. “Get away from there!”

Will ripped one edition off the window with a brisk, downward yank. There was a crash as the man shot up, sending his chair flying. “What the—”

Will tore off another, then turned calmly, crumpling the paper in one hand while he reached in his pocket with the other. He found a coin, not caring what it was, and flipped it at the counter. “Tell Sharp that one of his paying customers doesn’t like his newspaper, all right?” He spun on his heel and moved toward the door.

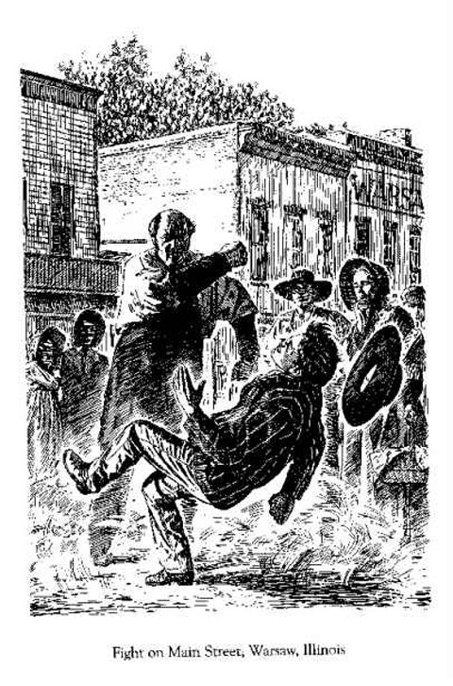

With a roar, the man darted down the counter. Will had expected no less and backed out the door swiftly, not wanting to be caught inside the narrow confines of the office. He shut the door calmly in the man’s face; then, as the man ripped it open again, he moved out into the center of the street, nearly knocking two women off the sidewalk as he did so.

The man stopped for just a moment, dazzled by the bright sunlight. Then, seeing Will waiting for him, he lumbered out into the street, swinging the hamlike fists even as he came. Will didn’t have time to entertain any second thoughts about the wisdom of what he had just done. Nor did he try to sidestep the rush. Instead, at the last second, he dropped into a crouch, as the first mate on his ship had once taught him, and let the man trip on him and hurtle over the top of him. There was a solid thud, and clouds of dust billowed up around them.

Will really had no desire to fight the man. He had done what he needed to do, and now he just wanted to disengage and get out of there. But he had made one miscalculation. As the man went over the top of him, his knee caught Will squarely in the side. It felt like someone punching a hole through the side of a barrel. Will too went sprawling, rolling over and over, clutching his chest, gasping for air.

The man was up again, and Will managed to stagger to his feet. People were shouting and running towards them. Already there was a small circle gathering around them. On the voyage to China, Will’s ship had stopped at Lisbon, on the Iberian Peninsula, to get supplies and to provide some much-needed shore leave for the crew. That Sunday, the captain had taken the ship’s officers to a bullfight. That was the image that came to Will’s mind right now. The typesetter’s head was down and swinging slowly back and forth, as though targeting his prey. Then he lunged. This time Will did try to sidestep, driving his fist into the man’s tremendous girth as he passed by. But the man was too quick for him. He hooked left with one of those huge fists. Fortunately, Will’s shoulder was still up from throwing his punch and that took the main force of the blow. But the man’s fist, still hooking, glanced off the shoulder and smashed directly into Will’s face.

Will went down and he went down hard. Blood spurted from his nose, and suddenly there were brightly colored lights flashing behind his eyes. Somewhere he heard a voice shouting at him. “Get up, Will! Get up!” He was conscious of the danger. If the man dropped on him while he was down, it would be over. He tried to push himself up, realizing with some wonder that the voice was his own and that it was only in his mind. And then his elbows gave way. With a low moan, he fell back down, face first into the dust of the street, and everything went black.

“I think he may have cracked a rib, and his shoulder is definitely sprained.” The doctor glanced at Will, but then went on talking to his father. “The nose is fine, but I suspect he’ll end up with an eye that is a real conversation piece.”

“How long should he wear the sling?” Joshua asked.

“About a week, I’d guess.” He turned now to Will. “You’ll know. When it stops hurting when you move it, then you can get rid of the sling.”

“What about the binding around my chest?”

“The same. When you can take a really deep breath and not have it hurt you too badly, then it’s fine. You’ll still be tender, but you’re young. You’ll heal soon enough.”

Joshua stood. “Thank you, Doctor. What do we owe you?”

“Two dollars will cover everything.”

“I’ll get it,” Will said, trying to reach around for the purse he kept in his back pocket. He gasped, wincing with the pain.

Joshua just shook his head, trying to hold his patience, and paid the man.

As they came back out on the street again, Joshua looked at his son. “You ready to talk about it now?”

Will shook his head. “No.”

“You know that Thomas Sharp is one of our customers, don’t you?”

Will’s head came up with a jerk.

“That’s right. I’ve hauled many a load of paper for the

Signal.

”

“Then I’d like to stop doing that.”

Joshua’s nostrils flared and there was a quick intake of breath. But Will wasn’t up to any more battles today. Holding his damaged arm with the other, he moved away, not waiting for his father to say anything further.

Chapter Notes

It was 1837 when a French scenic artist named Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, having worked in partnership with an inventor, perfected the process of fixing photographic images permanently on sheets of silver-plated copper. This was to become the forerunner of modern photography. Daguerre’s first photos required several minutes’ exposure time. By the end of 1840, a change in the chemicals used, coupled with a significantly improved lens, not only greatly reduced the time necessary for the photo but also gave a richer image. Even then, head clamps were often used to ensure immobility during the picture taking. Though expensive, daguerreotypes were widely used in Europe and the United States until the 1850s when ambrotype, tintype, and paper photographs replaced them. (See

World Book Encyclopedia,

1994 ed., s.v. “Daguerreotype.”)

Though it may seem odd to modern readers to have school starting in early August, the traditional school year that we are familiar with was not yet established back in the mid-1800s. Many of the schools of that day, particularly in areas that depended heavily on farm labor, had very short terms, generally during the winter months only. But as cities, such as Nauvoo, began to develop, longer terms were tried by some schools. We know of one Nauvoo school which had a term that went from May to December. (See

In Old Nauvoo,

pp. 242–43.)

Thomas Sharp and the

Warsaw Signal

were to play an important role in the history of the Saints during the Nauvoo period. The editorial stance and accusations depicted here accurately reflect his bitter opposition to the Saints.

Chapter 7

Caroline looked up as the bell in the front entry began to tinkle. “I got it,” Savannah shouted from in the dining room. In a moment, she came racing around the corner on a dead run and nearly skidded into the wall as she hit the throw rug at the end of the hall.

“Careful, Savannah.” Caroline sighed wearily. “Oh, that girl.”

Olivia, who had been at the piano practicing, swung around to listen for who it was. Will, lying on the sofa reading, laid his book down and did the same.

“Well, good morning, young lady.”

“Hello, Brother Joseph,” Savannah’s voice came back.

At the sound of Joseph’s voice, Caroline straightened and put aside her knitting. Will groaned as he pulled himself up, careful not to bump his one shoulder. Olivia stood and walked to the parlor entry.

“And how is the prettiest redhead in all of Nauvoo today?” they heard Joseph say.

“Grandpa says I’m the prettiest redhead in the whole county,” came the quick reply.

As they heard Joseph’s explosion of laughter, Caroline stood too. Shaking her head, she moved to stand beside Olivia just in time to greet Joseph as he came, still chuckling, to where the entry hall opened into the parlor. “Hello, Brother Joseph,” Caroline said. “I see you’ve already been greeted by my humble daughter.”

“I have,” he laughed. He reached down and picked Savannah up, lifting her until her face was right next to his. “Actually,” he said in a conspiratorial whisper, “I would be surprised if you’re not the prettiest redhead in

three

counties.” She giggled, knowing now that she was being teased but accepting the compliment anyway. Joseph let her down again and stuck out his hand. “Good morning, Caroline. Morning, Olivia.”