The Work and the Glory (462 page)

Matthew closed his eyes. The men thought it was in fear. In reality, he was searching his mind to see if he could remember the scripture from the Second Epistle to Timothy he had first memorized in England. After a moment his eyes opened and he looked straight into the eyes of Pulsipher Scadlock and began once again to quote the words of Paul. “‘I am now ready to be offered, and the time of my departure is at hand. I have fought a good fight. I have finished my course. I have kept the faith. Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord shall give me at the last day.’” He took a breath and squared his shoulders. “I won’t deny what I know to be true, Mr. Scadlock. You’re going to have to kill me.” He let his eyes sweep from man to man. “And may God have mercy on all of your souls.”

For what seemed like a full minute, there was not a sound in the small grove of trees. Finally, Scadlock shook his head with sadness. “This pains me, boy, believe it or not. I’ve got to hand it to ya, ya got grit.” He looked around. The men couldn’t meet his glaring challenge. One by one their eyes dropped or they turned their heads. There was a snort of disgust and Scadlock turned back to the horse. He took a step forward, preparing to strike the animal across the rump.

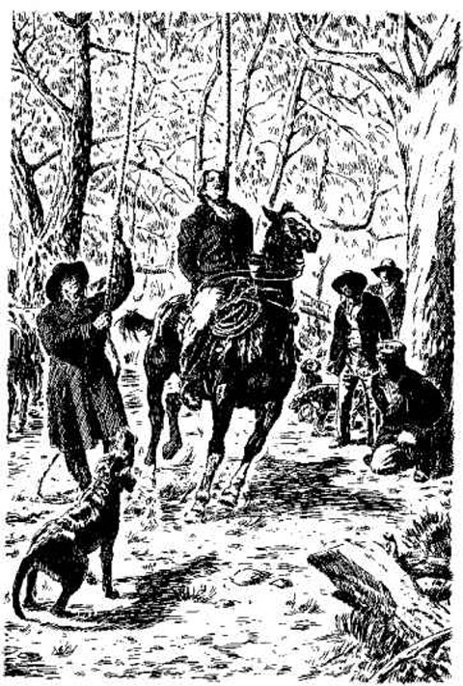

Several things happened all at once then. “Giddyap!” Matthew shouted. At the same instant, he drove his heels into the horse’s flanks. The horse, which seemed to sense that something was up and was standing fully alert, leaped forward like a startled antelope. Caught completely off guard, Scadlock barely had time to raise his hands. The bearded Mormon-hater screamed as the full weight of Matthew’s body hit the rope and snapped it taut across the tree limb. Scadlock’s arms were jerked violently forward, nearly yanking him off his feet. For one instant, Matthew swung wildly back and forth, gasping and croaking. Then Scadlock couldn’t hold it. The rope pulled free of his hands, whipping across the bare flesh of his palms. He screamed again. The rope flew free and Matthew crashed to the ground.

At the same moment, Derek, who had been completely forgotten in the final tense moments, scrambled up into a half crouch. Then he launched himself in a hobbling sprint for Scadlock. His hands were tied too, but he lowered his right shoulder and drove with all his power straight into Scadlock’s abdomen. It didn’t have quite the same effect as being hit by a fist, but Scadlock was staring at the palms of his hands, now bloody from the rope’s burning power, and he didn’t see Derek coming. He went down hard, gasping and retching.

John Webster and the other men were stupefied, and it took them a moment to react before they dove for their rifles. But Webster was the quickest. He came up with his first and leveled it at the bellies of the other men. “Leave ’em, boys. Leave ’em there.” They straightened slowly, raising their hands. Behind him, Scadlock was grunting and gasping, getting back up to his knees. Webster half turned to watch. The big man looked momentarily bewildered; then he saw Derek, head down and panting heavily, and Matthew squirming on the ground, the rope coiled around him. Then he saw Webster with his rifle, and something inside him snapped. With a cry like that of a mother grizzly bear cut off from her cubs, he was up on his feet and lumbering toward his neighbor, cursing and swearing in an incomprehensible stream.

Webster didn’t move. He didn’t swing the muzzle of the rifle around to face Scadlock or raise it to defend himself. “Watch out!” Derek cried as Scadlock hurtled forward.

But Webster knew exactly what he was doing. As Scadlock launched himself, Webster moved back one step, swung the butt of the rifle, and caught Scadlock directly behind the ear with it. There was a great thud as Matthew’s would-be executioner hit the ground and slid a few inches facedown in the mud.

“Pa!” his son cried, and ran to drop beside him. At the same time, Derek ran to Matthew and backed up to him, trying to take the noose up and over his head with his tied hands. There was already a bright red welt, two inches wide, all around Matthew’s neck.

Webster stepped away, looking at the men now. “All right, boys. You said you’re not interested in a lynching any more than I am. So this is over right now. Caleb, go cut those two men free.”

There were slow nods, almost a visible relief. One of them pulled out a knife and went to Derek and Matthew. Another man was staring at the bulky figure on the ground before them. “What are you going to do, John?”

“I’ll wait here for Pulse to wake up. The rest of you take the dogs and go on home.”

“He’ll kill you!” Willie said, but curiously it was not said with anger. There was genuine concern for John Webster’s safety.

Webster shook his head. “Once the liquor wears off he’ll be manageable.” There was a rueful grin. “He’ll want to fight, but I can handle that.”

Free now, Derek helped Matthew to his feet and Caleb cut his hands loose as well. “What about us?”

Webster considered only for a moment. “Did you mean what you said about leaving Arkansas? Going home?”

“Yes. This was the last thing we planned to do.” There was a momentary, humorless smile. “Probably not our best idea.”

“Take that horse,” Webster said, pointing to the one Matthew had been on, “and mine—the pinto there. You can leave them in Bonnerdale at the general store. Then git on out of here.”

The missionaries nodded wearily. “Thank you.”

Webster’s face was very somber. “We know you meant well, coming out here to see us and all, but we’re quit of the Church now. It’s best you not come back.”

There were grunts and angry nods from a couple of the men. Had Webster taken the missionaries in warmly, he might have had a rebellion. But if they were leaving the state, well then . . .

Matthew walked slowly to the horse. He took the reins and led it back as Derek got the pinto from where it was tied. As they swung up into the saddles, Matthew looked down. “Was that your boy who came to warn us this morning?”

Webster looked puzzled and shook his head. Willie Scadlock stood up, still looking down at his father. “No, that was my brother. Ma sent him.”

Matthew nodded. “May God bless her for her goodness.”

Derek looked down at the man with the rifle. “And God bless you, John Webster.”

There was a curt nod; then Webster turned and walked over to kneel down beside Pulsipher Scadlock. “Get some water from the creek, Willie,” he said. He did not look up as Matthew and Derek rode back out to the road and turned south toward Bonnerdale.

* * *

“How’s your neck?”

Without thinking, Matthew turned to look at Derek and winced as he did so. The welt around his neck had turned into an ugly mass of bruised and scraped flesh. It looked like some kind of horrible clerical collar. But Matthew forced a smile. “I think it’s stretched an inch or two. Jennifer Jo’s going to have to go up on tiptoes to kiss me now.”

Derek chuckled. “What ever made you spur your horse that way?”

Matthew sobered. “I don’t know. It was just a flash of thought. Suddenly I realized that Scadlock had made a mistake. He should have tied the rope to something solid or gotten on another horse and wrapped it round the saddle horn. He’s a big man, but I’m near to a hundred seventy-five pounds myself, I’d say. I just suddenly pictured that much weight hitting the end of the rope and knew that he couldn’t hold it, especially if he wasn’t ready for it.” He shook his head. “It takes longer to describe it now than it took for it all to come clearly into my mind.”

Derek said nothing. There was no need to. They rode on for several more minutes before Matthew spoke again. “When we get back to Little Rock, I’d like to start home.”

“I think it’s time,” Derek said. “Seems like we wore out our welcome here.”

Chapter 13

By the time Derek and Matthew returned to Little Rock and closed out their affairs and started home, it was the twentieth of February. It took them three more days to cover the one hundred and forty miles to Memphis, where they caught a riverboat. Two days later they disembarked at St. Louis. The ice running in the Mississippi farther north was starting to come in big enough chunks that it could tear a hole in the keel. Anxious now to return before their babies were born, they walked, rode, hitched rides with freight wagons or local farmers, and spent as little time eating and sleeping as they could possibly get by with. It was roughly a hundred and eighty miles from St. Louis to Nauvoo, an eight- to ten-day trip overland. They made it in seven. Late in the afternoon of March fourth, slogging along in a drizzling cold rain, Derek Ingalls and Matthew Steed returned to Nauvoo, having been gone four months, two weeks, and two days, and having traveled approximately fifteen hundred miles, the better part of that on foot.

The fortune that had smiled upon them so often during that time, and especially on the day they were pursued by Pulsipher Scadlock, continued to smile down upon them. Neither Rebecca nor Jenny had given birth by the time they arrived. It was barely five days later, on March ninth, 1845, that Rebecca Steed Ingalls gave birth to a squalling little girl whom they immediately named Leah Rebecca Ingalls. One week later, almost exactly to the hour, on March sixteenth, 1845, Jennifer Jo McIntire Steed brought forth another little girl. After some considerable debate, they named her Emmeline Steed, for Jenny’s grandmother back in Ireland.

About three weeks later, just after midnight on the sixth of April, the fifteenth anniversary of the organization of the Church, Jessica Garrett gave birth to a whopping boy. They named him Solomon Clinton Garrett—Solomon for his father, and Clinton for Jessica’s father, who had died two years before in Independence, Missouri, not having seen his daughter since she had fled Jackson County some eleven years previously.

In all three cases, the babies were healthy and strong. In the case of Jessica, having the baby healthy and strong brought a collective sigh of relief throughout the family. Jessica was just two months shy of her forty-first birthday when she gave birth. This would almost certainly be her last child. It was a joy to know it would also be without any problems.

In all three cases, when the letters arrived in Nashville from the new parents, Mary Ann waited until Benjamin was gone somewhere, or asleep, and then she wept because she could not see and hold her newest grandchildren.

On the twentieth of March, 1845, Savannah Steed, the firstborn child of Joshua Steed and Caroline Mendenhall Steed, turned eight years old. When her father asked her, some days in advance, what she wanted for her birthday, she answered without hesitation. “To be baptized.”

Joshua merely laughed and brushed it aside. When she refused to give him any other answer, he finally bought her a beautiful little gray Shetland pony with a finely tooled saddle and matching bridle. That worked its magic for over a month and she said nothing more. But as May came and the river ice disappeared, many children—and, in some cases, new converts—who had waited through the winter went down to the spot near the ferry dock and were baptized into the Church. That did it. Though the pony was loved and dearly treasured, Savannah now realized she had been bought off.

And life became miserable for Joshua.

“Papa?”

Joshua was at the small blacksmith shop they kept on the premises of his freight yard, helping prepare a horse for shoeing. He was bent over, the left front leg of the horse pulled up and held between his knees while he clipped around the edge of the overgrown hoof so it would take the shoe. At the sound of her voice, he jerked up, letting the horse’s leg slip out of his hands. “Savannah, what are you doing here?”

“I want to talk with you, Papa.”

“You what?”

“I need to talk with you, Papa.”

He shook his head, as the blacksmith stopped to watch. The man, a grandfather of fifteen, smiled and waved. “Good morning, Savannah.”

“Good morning, Brother Meyers.”

“Savannah, how did you get here?” Joshua asked her.

“I walked.”

“By yourself?”

“Yes. Mama couldn’t come.”

He threw up his hands. “Did she know you were coming?”

Savannah looked away, suddenly interested in the bellows that Brother Meyers had started to pump again. “What does that do?” she asked.

“Savannah!”

“Yes, Papa?”

“Does your mother know you’re here?”

“She does now.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I wrote a note.”

The blacksmith guffawed, then at Joshua’s look quickly turned around and began to select a pre-hammered shoe that would be closest to what they would need.

“You get yourself home right now, young lady.”

The dark red curls bounced vigorously as she shook her head. “I need to talk with you, Papa.”

He stepped back to the horse, turning his back on her, and picked up the front leg again. “I know what you want to talk about, and the answer is no. I’m busy, Savannah. I can’t talk.” He picked up the clippers again and started in on the hoof where he had left off.

She stepped closer. “Ew! Doesn’t that hurt him?”

He didn’t look up. “Savannah, I mean it.”

She looked up at the horse’s face, as if she hadn’t heard him. She watched intently as the clippers snipped off another piece of hoof. “Why doesn’t it hurt him?” she asked of the blacksmith this time.