The Work and the Glory (609 page)

The great storm that hit the Mormon Battalion on the night of 30 July tore down several large trees. Incredibly, no one was hurt. In the meadow where they had left their animals one ox was killed. Thomas Dunn, a battalion member, wrote of that night: “This appeared quite miraculous to us, but we considered we were in the hands of the Lord, for in his power, I trusted” (as quoted in

SW,

p. 64).

Chapter 19

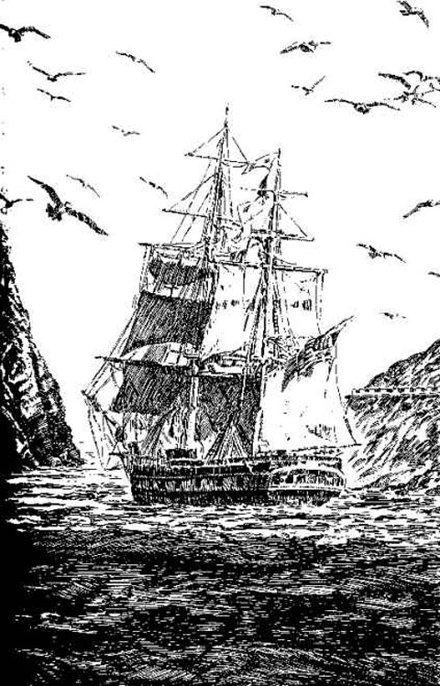

The fog was like a living thing. It swirled and moved around them in constant motion. Sometimes it would lift enough that they could see out a hundred yards or more across the water. Then it would close in again and they could scarcely make out the prow of the ship, a distance of no more than twenty-five or thirty feet. But the sun was up now, and from the gradually increasing brightness above her, Alice could tell that the fog was thinning and would burn off in another quarter of an hour or so.

There was a sharp jolt as the baby kicked out sharply. She winced, then placed a hand on her stomach, smiling.

Yes, child. We are almost there. Can you feel it too?

She saw Will turn and give her a look of quick concern. He had evidently seen her jump. She gave him her most radiant smile. He smiled back, then looked forward again.

She was glad. If he had looked at her too closely, he might have seen into her heart, and for now she didn’t want that. What would he think of this woman who was his wife? At the moment she was euphoric to the point of giddiness, feeling as if someone had given her a very strong draught of wine. And why not? she decided in her own defense. Six months of sea life were about to come to an end. Half a year—the longest of her entire life—was now over. One hundred and eighty days of almost unbearable monotony. To only smile at this moment showed a remarkable amount of restraint. If she followed her natural inclination, she would be up on the bridge beside Captain Richardson shouting to everyone who would hear her: “It’s over! At last it’s over!”

She and Will were not alone on the deck. It was crowded, and she guessed that virtually every passenger who was able had come topside. She cocked an ear to see if she could still hear it, then felt a deep satisfaction. It was the sound of surf pounding against a shore. She lifted her head, glaring at the mists that surrounded her.

Be gone,

she commanded sternly.

You are ruiningthis for me.

“It may just be an island.”

Alice whirled to see who dared speak such blasphemy. “No,” she said fiercely to the man who had spoken it to his wife. “There are no islands here.” She turned to Will, who was staring at her in surprise. “Tell them, Will. There are no islands here.”

“Well, the charts do show a small group called the Farallon Islands about twenty or twenty-five miles off the mainland.” He rushed on when he saw the look Alice shot him. “But we passed them off the starboard side sometime during the night. No, what you hear is the mainland. I would guess from the sound that we’re not much more than a mile offshore now.”

Alice nodded in triumph at the puzzled brother and his wife, who weren’t sure what they had done to generate such a passionate outburst. Alice ignored them, just as she ignored Will’s questioning glance.

No islands. Not now.

Captain Richardson had struck most of the sails, and they were moving forward very slowly. Two sailors stood at the prow with a sounding line—long ropes with knots every six feet, or every fathom, and a lead weight tied on one end. Another of the crew was high overhead in the crow’s nest at the top of the tallest mast. Occasionally they could look up and see him; mostly he was shrouded in the mists. Every eye was fixed dead ahead. It was not a comfortable thing to bring a ship in this close to shore and not be able to see what lay in your path.

One of the sailors at the prow dropped the sounding line over the side again. The coiled rope unwound with a soft hiss until it finally was gone and snapped taut against the hawser to which it was tied. The sailor turned, cupped his hands around his mouth, and shouted back toward the bridge. “Still twenty fathoms or more, Cap’n.”

“Aye,” Richardson called back. “I want a sounding every minute.”

“Aye, sir.” The two sailors began reeling the dripping rope back in again, coiling it neatly as they did so. Alice peered forward. The fog was thinning noticeably now, looking like clouds of dust gusting before the wind. Suddenly there was a cry from above them, and every head jerked upward when it came.

“Land ho! Half a mile dead ahead off the port bow.”

Alice swung her head to the left. There was a momentary glimpse of a high promontory of land and sharp cliffs that dropped to rock-strewn beaches. Much of the hillside was golden brown, but here and there clumps of low green bushes clung to the hillsides. And then it was gone again.

“I saw it,” she cried, grasping Will’s arm.

“Yes!” he answered.

Excitement swept the group. A stiffening breeze was blowing from behind them, the warmer air over the water rushing in to replace the cooler air over the land. It was sweeping the fog bank away in its rush to make landfall.

Then there was a collective gasp, followed by cries of joy. Off to the left of the ship, framed in perfect clarity by the surrounding mists, steep hillsides rose straight up out of the sea. They could see the white line of surf, rocky beaches, seabirds soaring over the heights, the thick green foliage which capped the upper reaches. What was most thrilling was that the landmass did not spread clear across their path. Directly in front of them it was clear water. The land came out into the sea, then stopped.

There were groans as another fog bank rolled back across their view. But the cloud was low enough that it didn’t reach the top of the mast, and the man in the crow’s nest could see over the top of it.

“Land ho!” the lookout cried again. “Another peninsula off the starboard bow, sir. Roughly the same distance as the first.”

“Can you see if the land comes together?” the captain shouted.

“There are two points of land jutting into the sea, but nothing dead ahead, sir.”

“Sounding line?”

“Still more than twenty fathoms, sir,” came the reply.

Will nodded in satisfaction. The sounding line had only twenty knots on it, but that was more than enough. If it didn’t hit bottom, that meant they had at least twenty fathoms, or a hundred and twenty feet, of water beneath the hull. Since the ship drew only between two and three fathoms when it was fully loaded, as it was now, there was no threat of beaching her yet.

The

Brooklyn

moved forward slowly, the sounding linesman crying out periodically, the lookout in the crow’s nest reporting regularly. The breeze was strong enough now that it was whipping up the first of the whitecaps. The fog was clearing rapidly before it. Then suddenly it was clear, with only wisps of the fog before them. Directly ahead there was nothing but water. On both sides the land rose sharply out of the sea, but the distance between the two points was at least a mile.

Will gripped Alice’s arms. “It’s the Golden Gate, Alice. The entrance to San Francisco Bay. We’re there.”

Alice reached out and took Will’s hand and squeezed it hard, beaming with joy. She went up on tiptoe and put her mouth to his ear. “You are a very fortunate man, Will Steed.”

“I am?” he whispered back. “Why is that?”

“Do you know what day it is today?”

“The last day of July.”

“That’s right. Do you remember what I told you when we left the Sandwich Islands?”

He frowned, clearly stumped. Then suddenly the frown disappeared and he grinned broadly and nodded. “I do.”

“That’s right,” she said happily. “I told you that you had July and then you’d better have me to California.”

“Mr. Brannan! Come to the bridge immediately.”

Will turned in surprise. It was Mr. Lombard, one of the officers. He was on the bridge beside Captain Richardson, who had a telescope to his eye, looking up toward the headlands that towered above them now on either side. They were still wreathed in wisps of clouds and mist. Above the excited chattering of the passengers, the officer’s voice barely carried.

Lombard cupped his hands. “Mr. Samuel Brannan. Report to the captain immediately.”

Will squinted a little. He had come to know the officers well, and there was just a hint of anxiety in Lombard’s voice. “Stay here,” he said to Alice. “I’ll be right back.”

She turned but he was already pushing through the crowd toward the back of the ship. He arrived at the ladder leading to the bridge just as Sam Brannan and one of his counselors did. Will stopped. He didn’t want to assume he was wanted when he wasn’t, but Brannan motioned for him to come along.

Now the noise had subdued somewhat. The passengers seemed to sense that something was afoot and were watching curiously. When the three Latter-day Saints reached the two naval officers, the captain motioned them to follow and they went to the back of the bridge where they were out of sight of most of the passengers.

“Mr. Brannan,” said Captain Richardson, handing over the telescope, “take a look up on the point of that bluff.”

Will’s head snapped up. It took him only a second or two to see it, even without the spyglass. The edge of the cliff was lined with walls of stone. At regular intervals the tops of the walls were notched with square openings. At each opening Will could see the black snouts of cannon. This was a fort, and they were about to pass beneath a full battery of artillery.

Brannan put the glass to his eye, searched for a moment, then found it. He gasped softly.

“It has to be Mexican,” Mr. Lombard said. “And they’re looking right down our throats.”

“I suggest you get all of your people below decks, Mr. Brannan,” Richardson said, staring upward even as he spoke. “Just in case. We have no reason to expect that we’ll be fired on, but we can’t be sure.” Then to his officer he began snapping out orders. “Mr. Lombard, alert the crew. Get the five-pounder ready for action. Rig the sails for fast running on my command.”

The officer snapped out an “Aye” and was gone. Richardson turned back to Brannan. “We don’t want to frighten your people, Mr. Brannan, but we need to move with dispatch.”

Twenty minutes later the hold opened and someone came clattering down the ladder. “Mr. Brannan.” It was the voice of Mr. Lombard.

There was instant quiet below decks. Sam Brannan stood and walked to the doorway which led into the passageway. Will stood and edged closer so he could hear.

“Yes?”

“The captain says your people are welcome to come back topside,” the officer said. “We’ve passed the fort. Near as we can tell, it’s deserted. There’s no one there. We’re into the bay now.”

A great sigh of relief swept through the group as Brannan called back to Lombard, “Thank you. That is welcome news.”

Once they had cleared the entrance to the bay, and with the fog gone, the captain raised more sail and the

Brooklyn

moved along briskly again. The passengers lined the rails all along both sides of the ship. For a time they kept looking back nervously, watching the fort they had passed, but they were beyond the range of her guns and soon the threat was forgotten. Now many of them were crying out, pointing to this or that sight in case someone had missed it.

Alice’s own excitement—dashed so abruptly when they had to go back below decks—had quickly returned, and her eyes drank in everything eagerly. They had come through the narrow passage known as the Golden Gate, and now the water opened up into a huge bay, a great inland sea. Directly ahead and to their left a barren, rocky island thrust itself out of the bay, as though it were guarding the entrance. To the left, perhaps two miles farther on, another small island was wreathed in the last of the morning fog. Seabirds were everywhere, dipping, soaring, bobbing on the water, hopping awkwardly along the rocks. Across the bay the land came down to meet the water, forming the eastern shore. It was a bleak, treeless shore. Here there was little green to be seen. The summer sun had turned everything brown. It was nothing like Robinson Crusoe Island or Honolulu, but Alice didn’t care. This was North America, the same continent from which they had left. More important, it was their final stop. The voyage was done.

A movement caught her eye, and she turned to see a line of soldier pelicans wing past them, barely skimming above the choppy water. She felt like shouting at them, telling them that Alice and Will Steed would soon be moving in to live with them.

“Sail ho!”

It was a cry from the man in the crow’s nest again. Every head turned up to see which way he was pointing, then jerked around to look in that direction. It took almost a full minute more before the ship rounded the land enough for the rest to see what he had seen. Once again there was momentary panic. Once again they were roughly jerked back to the painful reality that they were entering a war zone.

“It’s a man-o’-war!” the lookout cried. “Twenty guns.”

There were cries of alarm, and several began running for the holds that led down to their quarters. Mothers yelled for children. Husbands moved to find their wives.