The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature (6 page)

Read The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature Online

Authors: Daniel J. Levitin

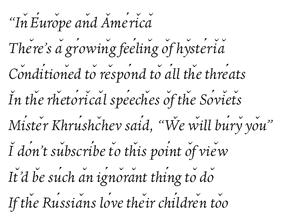

As we saw that good poetry must, Sting’s words create a rhythmic pulse. We can see this visually by adding diacritical marks showing the accent structure. The first line begins somewhat leisurely with eight syllables, and only two of them are stressed. The second line picks up the pace with eleven syllables, three of which are stressed, and more than half of which (six) begin with consonants. This trend continues in line three, where nine of the ten syllables begin with consonants. The combined effect of all these consonants is like a series of small explosions (they literally

are

explosions as air is thrust out of your mouth, something it doesn’t do with vowels) and these serve to propel the lyric forward.

are

explosions as air is thrust out of your mouth, something it doesn’t do with vowels) and these serve to propel the lyric forward.

In normal English speech, we tend to raise the pitch of syllables that are stressed or accented and lower the pitch of unstressed syllables, as is the case in many (but by no means all) languages. If we violate this in English, it becomes confounded with the rising intonation we normally use to indicate a question. For example, we would normally say the word

Eu

-rope by making the first syllable a little louder than the second and by dropping the pitch of the second (unstressed) syllable. Lowering a pitch like this usually makes the syllable sound unstressed. If instead, holding loudness manipulations the same (that is, keeping /Eu/ no louder than /rope/), I

raise

the pitch of the second syllable, it sounds like I’m asking a question, or like I’m unsure that I’ve chosen the right word. (Or like I’m fifteen? Ya know? Like, where every statement sounds like it’s a question? Even assertions? Like this?)

Eu

-rope by making the first syllable a little louder than the second and by dropping the pitch of the second (unstressed) syllable. Lowering a pitch like this usually makes the syllable sound unstressed. If instead, holding loudness manipulations the same (that is, keeping /Eu/ no louder than /rope/), I

raise

the pitch of the second syllable, it sounds like I’m asking a question, or like I’m unsure that I’ve chosen the right word. (Or like I’m fifteen? Ya know? Like, where every statement sounds like it’s a question? Even assertions? Like this?)

In “Russians,” Sting artfully interposes pitch accents and linguistic accents. This breathes life into the lyrics by introducing the unexpected, and allowing the text and melody to mutually support (but not entirely determine) one another. Where the melody rises, it sometimes rises on syllables that are unstressed. Such a technique would not work well in a dance or funk song, where the linguistic and melodic accents need to line up in order to give an unambiguous sense of the beat. Think “I Got You (I Feel Good)” by James Brown:

I feel good, I knew that I would

. . .

I feel nice, like sugar and spice

So good, so nice, I got you

Apart from the fact that all (but one) of the words are monosyllabic, the accent structure of the melody supports the accent structure of how this might be spoken—contributing to the pounding insistence of the groove.

“Russians” delivers as a song lyric because it marries text to melody, and because the lyrics feel effortless. It succeeds as a poem because even without the melody, it conveys its own rhythm, the forward momentum created by its accent structure and use of plosive consonants.

“Amelia” and “Russians” demonstrate great beauty in language and expression, used to convey an intensely imaginative interpretation of their subjects. Rather than delivering a literal description, they effectively capture feelings and impressions of events by telling us the most evocative parts of the story—often with figurative language, instead of the sort of objective details we would get in a newspaper article. We sense in them also a drive toward art—an unstoppable internal force that impelled the writer to write. In these lyrics, as in many great works of art, we feel an inevitability about them—that they have always existed and were just waiting to be discovered. When attached to the song, the words evoke additional emotions because of the harmonic tension that the musical notes add. Together, the lyrics plus melody, harmony, and rhythm bring nuances and shades of meaning that the words alone can’t deliver.

Both poetry and lyrics and all the visual arts draw their power from their ability to express abstractions of reality. When the poet Herbert Read wrote,

I believe he was referring to this abstraction process that is intrinsic in the creation and appreciation of all artistic objects, and that is a feature of the musical brain. Drawings, paintings, sculpture, poems, and song allow the creator to represent an object in its absence, to experiment with different interpretations of it, and thus—at least in fantasy—to exert power over it. Songs and poems derive their ultimate power in this way.

Art, at the dawn of human culture, was a key to survival, a sharpening of the faculties essential to the struggle for existence. Art, in my opinion, has remained a key to survival.

Songs give us a multilayered, multidimensional context, in the form of harmony, melody, and timbre. We can experience them in many different modes of enjoyment—as background music, as aesthetic objets d’art independent of their meaning, as music to sing with friends or sing along with in the shower or car; they can alter our moods and minds. Each of the elements of melody, rhythm, timbre, meter, contour, and words can be appreciated alone or in combination. “I Got You (I Feel Good)” may not have changed the course of human history, but it has been enjoyed by millions of people over many millions of hours. To the extent that we are the sum total of all our life’s experiences, it has become a part of our thoughts, and (as neuroscientists know) that means a part of the very wiring of our brains.

But that is not the same as guiding human destiny.

The World in Six Songs

is the story of just how music has changed the course of human civilization, in fact, the story of how it made societies and civilizations possible. Other art forms—poetry, sculpture, literature, film, and painting—can also fit into these functional categories, but this is the story of music and its primacy in shaping human nature. Through a process of co-evolution of brains and music, through the structures throughout our cortex and neocortex, from our brain stem to the prefrontal cortex, from the limbic system to the cerebellum, music uniquely insinuates itself into our heads. It does this in six distinctive ways, each of them with its own evolutionary basis.

The World in Six Songs

is the story of just how music has changed the course of human civilization, in fact, the story of how it made societies and civilizations possible. Other art forms—poetry, sculpture, literature, film, and painting—can also fit into these functional categories, but this is the story of music and its primacy in shaping human nature. Through a process of co-evolution of brains and music, through the structures throughout our cortex and neocortex, from our brain stem to the prefrontal cortex, from the limbic system to the cerebellum, music uniquely insinuates itself into our heads. It does this in six distinctive ways, each of them with its own evolutionary basis.

I attended the annual meeting of Kindermusik teachers this summer. Parents, children, and teachers came from more than sixty countries to participate in workshops and listen to lectures. The highlight of the conference for me was the music before the keynote speech. Fifty young children, between the ages of four and twelve, sang this song, based on a traditional German folk song, accompanied with syncopated clapping and synchronized movement:

All things shall perish from under the sky

Music alone shall live

Music alone shall live

Music alone shall live

Never to die.

Pairs of children from different countries took turns at the microphone, singing lines from the song in their native languages: Cantonese, Japanese, Romanian, !Xotha, Portuguese, Arabic, with each stanza ending in the English refrain in three-part harmony:

“Music alone shall live, never to die.”

And the music that will never die has been with humans since we first

became

humans. It has shaped the world through six kinds of songs: friendship, joy, comfort, knowledge, religion, and love.

became

humans. It has shaped the world through six kinds of songs: friendship, joy, comfort, knowledge, religion, and love.

CHAPTER 2

Friendship or “War (What Is It Good For?)”

I. It is the near twilight hour, the fog hanging thick, close to the ground like a heavy, leaden weight. Imagine that you’re an early human, sleeping with your villagers, huddled together on the ground, near the dying embers of the fire circle. First there is a feeling that disturbs your sleep—not all of your group is roused, but you notice that a few others were also disturbed—by a vibration more than a sound. And you wonder: Was it real or a dream? Rumbling, a boom-boom-ka-boom like distant thunder, like rocks tumbling. The earth shakes and then the sound comes closer, louder; your body is being assaulted. Drums are coming toward you, a purposeful, synchronized stampede, like fifty rhinoceroses, coordinated, all of one mind, as though they have devised a terrible, directed plan for attack and total destruction. It has to be real, you think, but it is a sound you’ve never heard before. What starts as a quiver of apprehension turns into collective fits of shaking as all of your family and friends wake and tremble with helplessness, all the gumption draining out of your bodies before you even know what is going on. The terrifying synchrony of it, the bone-shaking intensity of it, the sheer loudness. Do you run or prepare to fight? You sit frozen, in awe, paralyzed. What in the world is happening? As they crest the hill, you see them, and for a brief moment before the deafening sounds knock you senseless you see a band of warriors banging on drums in an eerie demonstration of coordinated, malevolent power.

Throughout history, tribes often attacked their enemies stealthily, in the dead of night while their opponents slept. Clever tribespeople, lucky recipients of a bit more cognitive capacity than their neighbors (thanks to random mutation), at some point recognized the power of drum music to incapacitate the enemy, to sap their resolve and simultaneously impassion their own warriors. Each drum tuned slightly differently, skins stretched over wooden stumps, sticks, and rocks knocked together; shells and beads banged, hit, struck, scraped, and shaken: the sound of a well-coordinated, well-practiced single mind. If these invaders could synchronize so tightly to something as nonvital as drumming, that same synchronization put into the service of killing would be so relentless and merciless as to crush even the most formidable resistance.

When Joshua fit de battle of Jericho, it was not melody that made the walls come tumbling down, according to one rabbinic midrash, it was the rhythms of the Hebrew army drum corps. And it was the terrified Jerichoans who themselves opened the walls to the invaders, realizing the futility of putting up a fight, hoping that their conciliatory gesture would eke out a trace of compassion. (It didn’t.) At the foot of Balin’s tomb in

The Lord of the Rings,

surrounded by dozens of skeletons, Gandalf reads the last entry from the watchman’s logbook: “The ground shakes. Drums . . . drums in the deep. We cannot get out. A shadow lurks in the dark. We can not get out . . . they are coming.”

The Lord of the Rings,

surrounded by dozens of skeletons, Gandalf reads the last entry from the watchman’s logbook: “The ground shakes. Drums . . . drums in the deep. We cannot get out. A shadow lurks in the dark. We can not get out . . . they are coming.”

II

.

It is 7:45 A.M. on a November morning at a high school in Kansas City, Missouri, fifteen minutes before the first period bell rings. Out in back of the school, near the Dumpsters and an abandoned basketball court, a group of students smoke cigarettes. For some it’s the first of the day, for others their third. They are not the good students, the star athletes, members of the chess club, glee club, or drama club. They aren’t the worst students either, the ones who are being threatened with expulsion or who are being evaluated by a stream of head-scratching school psychologists. These are average students who would otherwise go completely unrecognized and unnoticed by the rest of the school except that they come here several times a day. Most have been in trouble with their teachers or the principal for breaking one rule or another, but nothing serious—being in the hall without a pass, tardiness, late homework—crimes of laxity and neglect, not of violence. The alley where the municipal garbage trucks come has been named Tobacco Road by generations of students at the school. The morning cigarette ritual is followed by the ten o’clock mid-morning recess, lunchtime, and afternoon recess cigarette breaks. They blow smoke rings; they spit. The boys talk about cars they know they’ll never own, and Bruce Lee movies they’ve memorized. The girls talk about older siblings who don’t come home at night, with mind-numbing jobs and boyfriends.

.

It is 7:45 A.M. on a November morning at a high school in Kansas City, Missouri, fifteen minutes before the first period bell rings. Out in back of the school, near the Dumpsters and an abandoned basketball court, a group of students smoke cigarettes. For some it’s the first of the day, for others their third. They are not the good students, the star athletes, members of the chess club, glee club, or drama club. They aren’t the worst students either, the ones who are being threatened with expulsion or who are being evaluated by a stream of head-scratching school psychologists. These are average students who would otherwise go completely unrecognized and unnoticed by the rest of the school except that they come here several times a day. Most have been in trouble with their teachers or the principal for breaking one rule or another, but nothing serious—being in the hall without a pass, tardiness, late homework—crimes of laxity and neglect, not of violence. The alley where the municipal garbage trucks come has been named Tobacco Road by generations of students at the school. The morning cigarette ritual is followed by the ten o’clock mid-morning recess, lunchtime, and afternoon recess cigarette breaks. They blow smoke rings; they spit. The boys talk about cars they know they’ll never own, and Bruce Lee movies they’ve memorized. The girls talk about older siblings who don’t come home at night, with mind-numbing jobs and boyfriends.

None of them has much money, and with the cost of cigarettes approaching fifty cents each, they share a daily concern about where the money for the next pack will come from. But they are generous to anyone who shows up without a cigarette, sharing among one another what they have. When a stranger asks to bum a cigarette, several of the teens offer the outsider the hospitality of a shared nicotine rush. The group are alternately chatty and reflective as the chemicals simultaneously rouse their frontal lobes and calm their limbic systems.

Most of them have beat-up iPods or early MP3 players, but when they’re smoking together, the earbuds hang at their sides, and they listen to a boom box or portable player with a speaker built in. “The fidelity is whack,” says one, “but least this way we can all hear it together.” They tap their feet to 50 Cent—some of them raising the

back

of their heel and pounding it down on the pavement in time with the bass drum. They sing along with all the words to Ludacris, and when Christina Aguilera comes on, the girls do some steps, cop some poses, as the boys try unsuccessfully to feign disinterest. But it’s when an old song from thirty-five years ago comes on that one of the girls cranks the volume. Soon the entire group is moving as one to “Smokin’ in the Boy’s Room” by Brownsville Station:

back

of their heel and pounding it down on the pavement in time with the bass drum. They sing along with all the words to Ludacris, and when Christina Aguilera comes on, the girls do some steps, cop some poses, as the boys try unsuccessfully to feign disinterest. But it’s when an old song from thirty-five years ago comes on that one of the girls cranks the volume. Soon the entire group is moving as one to “Smokin’ in the Boy’s Room” by Brownsville Station:

Smokin’ in the boy’s room

Smokin’ in the boy’s room

Teacher don’t you fill me up with your rules

’Cuz everybody knows that smokin’ ain’t allowed in school!

Other books

Queen of Someday by Sherry Ficklin

Little White Lies by Katie Dale

Venus Envy by Louise Bagshawe

The Somali Deception Episode I (A Cameron Kincaid Serial) by Smith, Daniel Arthur

What the Waves Bring by Barbara Delinsky

Before, After, and Somebody In Between by Jeannine Garsee

The Alpha Gladiator by Erin M. Leaf

a Breed of Women by Fiona Kidman

The Devil of DiRisio by DuBois, Leslie

Out of Nowhere by Roan Parrish