The World That Never Was (86 page)

Read The World That Never Was Online

Authors: Alex Butterworth

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Revolutionary, #Modern, #19th Century

Although never an outright partisan of anarchism, Vladimir Burtsev showed exemplary tenacity in answering the intrigues of the Okhrana with investigations of his own. He would continue his crusade to uncover their spies, informants and provocateurs but could not match his success in exposing Azef and Harting, and by 1914 a number of ill-founded accusations had lost him the trust of those who, not long before, had looked to him for their protection. Briefly he flirted with Bolshevism, before turning implacably against Lenin.

The lives of many Russians who were prepared to reassess their loyalties were transformed, one way or the other, by the October Revolution of 1917: ex-Okhrana agents turned leaders of a soviet, like Rachkovsky’s forger Golovinsky, or revolutionary populists like Chaikovsky, who would lead the anti-Bolshevik government of the Northern Region during the

civil war, around Archangel. For Burtsev it merely brought more of the same. Arrested on Trotsky’s first orders he would once again be sentenced to the Trubetskoi bastion of the Peter and Paul fortress, just as he had been twice before under the tsar. After his release and flight abroad, the ‘Sherlock Holmes of the Revolution’ would accept a job with the British secret services that allowed him to continue his fight against tyranny from the margins; the challenges for an émigré dissident were much as they had always been, only with Lenin rather than a tsar now in the Kremlin.

The trajectory of Burtsev’s career had left him with few illusions about where the current of political poison ran, from its source in Rachkovsky’s Okhrana, through into the murky waters of the interwar years. The inquiry into the provenance of

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

began in earnest in 1920, when, in an article titled ‘The Jewish Peril: A disturbing pamphlet’,

The Times

had asked ‘What are these “protocols”? Are they authentic? If so, what malevolent assembly concocted these plans, and gloated over their exposition: prophecy in part fulfilled, in parts far gone in the way of fulfilment?’ In addition to the newspaper’s revelations concerning the work’s plagiarism of Joly’s

Dialogues

, the Russian Princess Catherine Radziwill revealed that Golovinsky himself had given her a copy in 1904, along with an explanation that Rachkovsky had indeed commissioned the forgery. However, neither of these new pieces of evidence could weaken the purchase that the

Protocols

had established as a propaganda weapon against Bolshevism, whose leaders were largely of Jewish extraction. Within a couple of years, two books elaborated on how the predictions in the

Protocols

had already been realised.

Secret World Government

, by an old Okhrana bureau chief called Spiridovich, and

World Revolution

, by the English proto-fascist Nesta Webster, fingered the diabolical banking family of the Rothschilds for everything from inciting the American Civil War and financing the Paris Commune, to the assassinations of Lincoln and Alexander II.

Societies turned upside down by war and revolution craved simple explanations for their misfortunes, and if blame could be laid squarely at the door of a conspiracy by an easily identified and little-loved ethnic group, so much the better. A touch of mysticism made the notion more intoxicating still: an account, for example, by the young Alfred Rosenberg of how, on opening a copy of the

Protocols

while a student in Moscow during the summer before the October Revolution, he had sensed ‘the masterful irony of higher powers in this strange happening’. A leading member of the German National Socialist Party since 1919, who would

go on to be Nazism’s leading racial theorist, Rosenberg’s publication of a German translation of the

Protocols

in Munich in 1923 provided inspirational reading for his close colleague Adolf Hitler while in prison following the failed Beer Hall Putsch of that year.

The seed fell on fertile ground, prepared years earlier when the teenaged Hitler had attended meetings held in Vienna by sympathisers with the Union of the Russian People, which Rachkovsky had helped found. Now, with the leisure that prison afforded him, the arguments he had heard there for the extermination of the Jews, hardened by the fictional fears of world conspiracy propagated by the

Protocols

, were burnished with the same abuse of science that had been used to strip the immigrant centres of anarchist militancy of their humanity, decades before. ‘The struggle in which we are now engaged’, he wrote in

Mein Kampf

, ‘is similar to that waged by Pasteur and Kock in the last century. How many diseases must owe their origins to the Jewish virus! Only when we have eliminated the Jews will we regain our health.’

Not long after Malatesta had died, it was the enduring toxicity of the

Protocols

that brought Burtsev to Berne in Switzerland in 1935, where the local Jewish communities had lodged a legal challenge against the book’s Nazi propagators. For too long the mystery of its provenance had fed public curiosity, and allowed the unscrupulous to insist that it was genuine. Laying to rest any residual uncertainty had become a moral imperative, which even the lack of hard, documentary evidence could not be allowed to impede. Alexandre du Chayla, who had corroborated Princess Radziwill’s wholly unreliable tale of Rachkovsky’s involvement with an account of his own meeting with the

Protocols’

first Russian editor, Sergei Nilus, agreed to testify; the secret 4,000-franc fee he commanded was yet another symptom of the ugly opportunism that had all along surrounded the book. Boris Nikolaevsky, the historian who, five years earlier, had had the chance to inspect a suitcase containing Rachkovsky’s private papers, agreed to conceal from the court his own conviction that the claims of Radziwill and du Chayla were groundless.

Burtsev was faced with a dilemma of his own, for whilst he had a good story to tell of how the

Protocols

had arrived in the world, one that was clear and coherent, it lacked any sure foundation. For when he had approached Rachkovsky to buy his collection of key Okhrana documents and a fragmentary memoir, his offer had been rebuffed, and, following the revolution of 1917, the vast and precious archive of the Paris Okhrana vanished into thin air, or into smoke and ash, as would later be claimed. There was little doubt, though, about which way Burtsev would jump.

And just as he had learned from the Okhrana’s methodology of surveillance and record-keeping in the 1890s, modelling his counter-intelligence activities on theirs, he now played his part with aplomb in weaving a myth of Okhrana conspiracy around the document’s origins as strange and compelling as that contained in the

Protocols

themselves: one that drew together high finance, espionage, diplomacy, court intrigue and personal rivalry. It is a testament to the subtle complexity of Rachkovsky’s devious mind that Burtsev’s story remains to this day only too plausible.

Rachkovsky’s dark genius would be demonstrated too by the abiding influence that the Okhrana’s methods exercised over the clandestine war waged between the heirs of communist revolution and capitalistic democracy for decades to come. The sixteen crates containing the lost archives of the Paris Okhrana finally came to light in 1957, proudly revealed to the press by the Hoover Institute in California, into whose safekeeping they had been entrusted by the last tsarist ambassador to France after he had smuggled them out of Paris in the 1920s. Since its inception in 1947, the Central Intelligence Agency had, it would later be revealed, analysed the archive closely in the process of developing its own tradecraft. The same thing was happening on the other side of the Iron Curtain. When it lifted, Oleg Kalugin, the highest-ranking Soviet intelligence officer ever to cast light on the inner workings of the KGB, confirmed that Okhrana methods had also been taught to the organisation’s agents throughout the Cold War. There is a striking irony in the fact that, while the Okhrana files and piled boxes of crumbling agent reports in the Paris Prefecture of Police provide a treasure trove of insights into late nineteenth-century policing of terrorism, only in Britain – so proud in the nineteenth century of its liberal traditions of policing – is access to the scant surviving documentary evidence of Special Branch’s early anti-anarchist activities still tenaciously guarded. Democracy and the existence of a political police force are, it seems, perhaps only compatible as long as certain more uncomfortable truths about the price of political stability are kept secret.

The greatest experiment in communism and the greatest abuser of its ideals, the Soviet Union was not, of course without its own more grotesque hypocrisies. But however undeserving its leaders’ claims to be the custodians of the nineteenth-century dream of freedom and equality, it is likely that, without them, the early dreamers might never have been memorialised. There might have been no Kropotkin Street and Metro station in Moscow, no crater named after Kibalchich on the dark side of the moon; and who would have thought to place a ribbon cut from a

Communard flag in the rocket named

Voskhod

, or

Dawn

, which launched into space in 1964?

From space, humankind could finally gaze upon the delicate blue globe that was its home, as Elisée Reclus had once planned to make possible through the artifice of his epic construction. Such a vision would, he was certain, prise open even the stoniest heart to the apprehension of a fraternity that ignored national borders, and divisions of class or religion. The world as it might one day be.

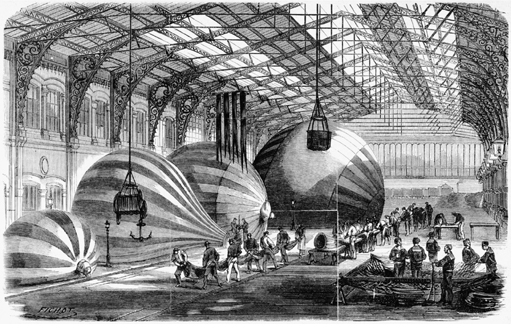

With the railways into Paris closed by the siege of 1870, the platforms of the Gare d’Orléans became production lines supplying balloons to Nadar’s aerostatic service.

An anonymous photograph looking down from the Butte Montmartre onto the artillery park that housed many of the National Guard’s cannon, whose attempted seizure by the regular army was the catalyst for civil war.

Père-Lachaise cemetery, scene of the last stand of the Communards on 28 May 1871; the survivors were executed against what would become known as the Mur des Fédérés, at the rear of the cemetery, which remains a site of annual pilgrimage.