The Worthing Saga

Authors: Orson Scott Card

“But Dal,” Bergen protested. “Somec is like immortality. I'm going on the ten-down-one-up schedule, and that means that when I'm fifty, three hundred years will have passed! Three centuries! And I'll live another five hundred years beyond that. I'll see the Empire rise and fall, I'll see the work of a thousand artists living hundreds of years apart, I'll have broken the ties of time—”

“The ties of time. A good phrase. You are ecstatic about progress. I congratulate you. I wish you well. Sleep and sleep and sleep, may you profit from it. But Bergen, While you fly, like stones skipping across the water, touching down here and there and barely getting wet, while you are busy doing that, I shall swim. I like to swim. It gets me wet. It wears me out. And when I die, which will happen before you turn thirty, I'm sure, I'll have my paintings to leave behind me.”

“Vicarious immortality is rather second rate, isn't it?”

“Is there anything second rate about my work?”

“No,” Bergen answered.

“Then eat my food, and look at my paintings again, and go back to building huge cities until there's a roof over all the world and the planet shines in space like a star. There's a kind of beauty in that, too, and your work will live after you. Live how you like. But tell me, Bergen, do you have time to swim naked in a lake?”

Bergen laughed. “I haven't done that in years.”

“I did it this morning.”

TOR Books BY ORSON SCOTT CARD

Future on Fire (editor)

Future on Ice (editor)

Harts Hope

Lovelock (with Kathryn Kidd)

Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus

Saints

Songmaster

The Worthing Saga

Red Prophet

Prentice Alvin

Alvin Journeyman

Heartfire

Speaker for the Dead

Xenocide

Children of the Mind

Ender's Shadow

The Call of Earth

The Ships of Earth

Earthfall

Earthborn

Orson Scott Card (hardcover)

Maps in a Mirror; Volume 1: The Changed Man (paperback)

Maps in a Mirror; Volume 2: Flux (paperback)

Maps in a Mirror; Volume 3: Cruel Miracles (paperback)

Maps in a Mirror; Volume 4: Monkey Sonatas (paperback)

NOTE: If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real people or event is purely coincidental.

THE WORTHING SAGA

Copyright © 1978, 1979, 1980, 1982, 1989, 1990 by Orson Scott Card

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this' book, or portions thereof, in any form.

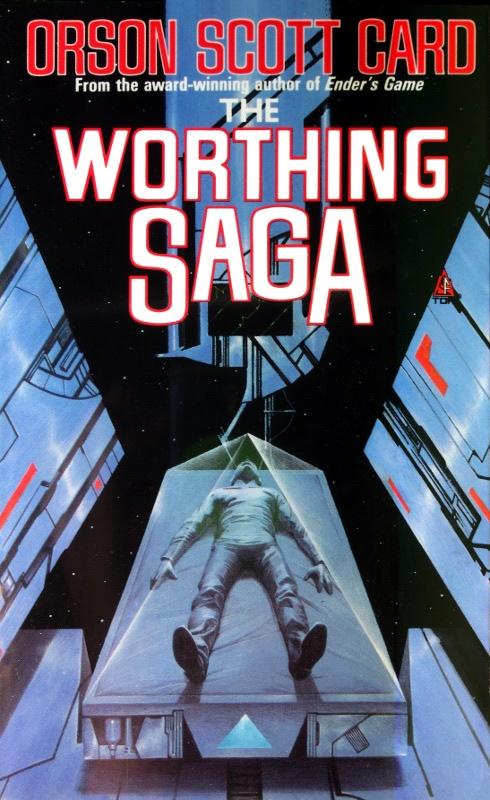

Cover art by Wayne Barlowe

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York. NY 10010

Tor is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

ISBN: 0-812-50927-7

First edition: December 1990

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8

Copyright © 1978, 1979, 1980, 1982, 1989 by Orson Scott Card

“Lifeloop” copyright © 1978 by The Condé Nast Publications Inc. (First published in Analog, October 1978.)

“Killing Children” copyright © 1978 by The Condé Nast Publications, Inc. (First published in Analog, November 1978.)

“Second Chance” copyright © 1979 by Charter Communications, Inc. (First published in Destinies, Ace Books, January 1979.)

“Breaking the Game” copyright ©' 1979 by The Condé Nast Publications Inc. (First published in Analog, January 1979.)

“Tinker” copyright © 1979 by Orson Scott Card. (First published in Eternity SF #2.)

Capitol: The Worthing Chronicle copyright © 1979 by Orson Scott Card.

The Worthing Chronicle copyright © 1982 by Orson Scott Card. (First published by Ace Books, The Worthing Chronicle superseded and replaced Hot Sleep, the author's first novel, also published by Ace.)

“Author's Introduction” copyright © 1989 by Orson Scott Card

“Afterword” copyright © 1989 by Michael Collings

This book brings together all the Worthing stories for the first time in one volume. In a way, the Worthing tales are the root of my work in science fiction. The first science fiction story I ever wrote was an early version of “Tinker”; I sent it to

Analog

magazine when I was nineteen years old.

At the time,

Analog

was the only science fiction magazine that listed itself in

Writer's Market

; since I had never read a science fiction magazine in my life, I knew of no others. “Tinker” reached

Analog

just at the time that longtime editor John W. Campbell died. His immediate successor rejected the story, but sent along an encouraging note.

I took this to mean that I was on the right track, and continued working on “Tinker”, and several related stories—“Worthing Farm,” “Worthing Inn,” and a much longer but never finished work about the first contact between the children of Worthing and the outside world. Soon after, while living in Ribeirao Préto, Brazil (I was serving as a missionary for the LDS church), I used my spare time to plot out and begin writing a novel-length prequel that explained why these people had psychic abilities and how they came to live on the planet Worthing. It was then that I thought of somec, with its torturous but forgotten pain; the planet Capitol; and the rather bizarre starship that Jason piloted. At the time my grounding in both science and science fiction were weak. I had read Isaac Asimov's

Foundation

trilogy—Capitol's derivation from Trantor should be obvious. But I had read little else, and as a result spent much time reinventing the wheel— so to speak. Eventually I left the work unfinished as I turned my hand to play writing and, after my mission was finished, to starting the Utah Valley Repertory Theatre Company.

In 1975, my theatre company in dire financial straits, I turned back to fiction. Since “Tinker” had received an encouraging note from

Analog,

I pulled out the manuscript and reread it. Apparently I had learned much in the intervening years, because I found it necessary to rewrite it from beginning to end. Again I sent it to

Analog;

again it was rejected with an encouraging note. This time, however, Ben Bova, who had since become editor, let me know why the story wasn't working. “

Analog

doesn't publish fantasy,” he said, “but if you have any science fiction, I'd like to see it.”

It hadn't occurred to me that “Tinker” was fantasy;

I

knew that there was ample science fictional justification for everything that happened. Furthermore, I had read a collection of Zenna Henderson's stories and knew that tales of people with extraordinary powers were within the realm of science fiction. Yet the impression “Tinker” leaves

is

that of fantasy— medieval technology, lots of trees, and unexplained miracles. I toyed with the idea of going back to the story of Jason Worthing, which would establish “Tinker” and all the other stories as true science fiction, but I was too impatient to work with a novel. Instead, I wrote the novelette “Ender's Game,” which became my first fiction sale and the foundation of my career as a fiction writer.

Still, it was not long before I returned to the Worthing stories. Even had I been inclined to neglect them, I could not have forgotten them: My mother kept asking me what I was going to do with my “blue-eyed people.” She had typed those early manuscripts for me—I was already a fair typist, but I couldn't match her error-free 120-word-per-minute artistry—and, as the first audience for the stories in the Forest of Waters, she believed, as I did, that there was some real power in them, even if I did not yet know how to tell the stories as well as I should.

By then I worked at

The Ensign

, the official magazine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons). Two other editors there, Jay Parry and Lane Johnson, were also working on fiction writing. We would spend lunch hours down in the Church Office Building cafeteria, eating salads, drinking nasty cheap soda pop, and developing story ideas. Most of my stories immediately after “Ender's Game” emerged from that creative maelstrom. It was then that I began using the idea of somec in stories like “Lifeloop,” “Breaking the Game,” and “Killing Children”; but the stories were never

about

the science fiction elements. Always they were about people and how they created and destroyed each other.

When Ben Bova invited me to submit a novel to him for a new series of books he was editing with Baronet and Ace, I immediately thought of my Jason Worthing novel, and started writing it. I showed the first fifty pages or so to Jay Parry, who told me it was too long. Too long? In fifty pages I was most of the way through the story. If I cut any more it'd be nothing but an outline. Then I realized that what Jay was really telling me was that the story

felt

long. I was trying to rush through the story so fast that I merely skimmed over the surface, never pausing long enough to show a scene that would allow the reader to become involved in the story, to care about a character.

I went back, slowed down, started over. Still I had trouble structuring the story as a coherent whole. My only experience was writing short stories, so in desperation I rethought the story as a series of novelettes, each from a different character's point of view. The result was a pretty good story marred by a weak, diffuse structure. Even so, it was deemed publishable, and under the title

Hot Sleep

it began to wend its way toward publication. In fact, he finished the final draft the night before my wedding to Kristine Allen, and on the morning of the wedding I photocopied it and dropped it off in the Church Office Building mailroom before going through the tunnel leading under Main Street to the temple, where my bride was waiting for me. She had some understandable doubts about what it meant to our future that I was a few minutes late for the wedding because I had to get a manuscript into the mail.

In the meantime, Ben Bova suggested that I collect the somec stories he had bought for

Analog,

and some new ones, and publish them in a collection with Baronet. The result was the book

Capitol.

Some of the new stories were good enough that they have found their way into this book. Some, however, were purely mechanical and soulless, and I have, out of mercy to you, dear readers, let them quietly expire. Yet at the time I wrote them, they were the best I could do with the subject matter, and

Capitol

came out in the spring of 1978 as my first published book of fiction—roughly at the same time as the birth of my first child, Geoffrey.

Hot Sleep

followed a year later, with a hideously ugly cover from Baronet that embarrassed me doubly because it faithfully illustrated a scene in the book. I learned then—as I have relearned since-that if there is a scene in a novel which, if depicted on the cover, would destroy the effectiveness of the book, that is the scene that will appear on the cover. Worse yet, the blurb writers had written “Hugo Award Winner” on the cover, even though I had come in second for the Hugo Award in 1978; it was the John W. Campbell Award (for new writer) that I had won at the Phoenix WorldCon (World Science Fiction Convention).

Soon after the book's publication I received a letter from Michael Bishop, a writer I had admired for some time, but had not met. He was apologizing in advance for his review of

Hot Sleep

in

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

. The review had not yet appeared, but it was too late to correct it, he said—he had criticized me for allowing “Hugo Award Winner” to appear on my book, only to discover a short time later that his own publisher had done the same thing to him, crediting him with awards he had not received. Thus began a friendship that continues today, though not without occasional tensions caused by our very different ideas of what good story telling consists of.

His review of

Hot Sleep

was highly critical, but it was also the most helpful book review I've ever seen. He called attention to the structural flaws in the novel in a way that helped me see what I had done wrong. I was then beginning work on my third novel,

Songmaster

, and was set to use a fragmented, diffuse structure just like the one in

Hot Sleep

; with Bishop's review as a spur, I found ways to bind a long story together as a single whole. It was the beginning of my understanding of story structure; my narratives came under my conscious control, and a whole new set of tools was available to me.

In the meantime, though, what could I do about

Hot Sleep

? I now knew how to write it properly and was deeply dissatisfied with it in its current form. Yet it was also selling steadily, which meant that to some readers it was adequate at least. Furthermore, I was now quite unhappy with the weaker stories in Capitol— and it too was still selling, bringing readers to associate my name with stories I no longer approved of.