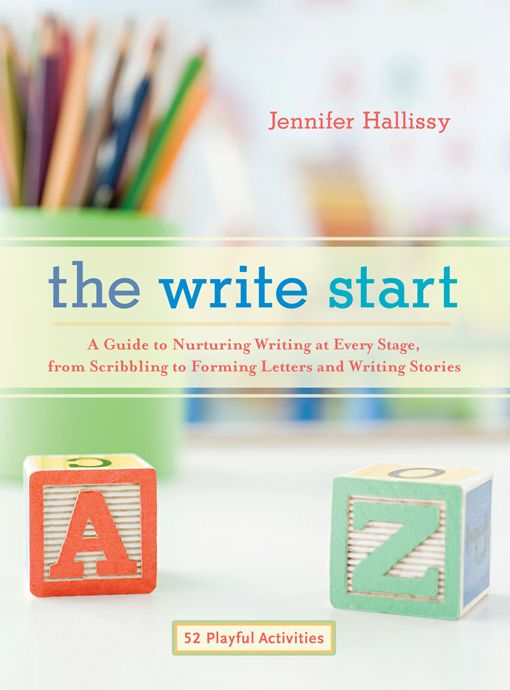

The Write Start

T

RUMPETER

B

OOKS

An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

© 2010 by Jennifer Hallissy

Template illustration “Anatomy of an Efficient Grasp” © 2010 by Joy Gosney

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hallissy, Jennifer.

The write start: a guide to nurturing writing at every stage, from scribbling to forming letters and writing stories / Jennifer Hallissy.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2321-1

ISBN 978-1-59030-837-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Children—Writing. 2. Children—Language. 3. Child development. I. Title.

LB1139.W7H35 2010

372.62′3—dc22

2010023070

To Bruce,

who built me the life of my dreams.

and to Jack and Gracie,

my dreams come true.

Contents

The Write Stuff: Tools, Materials, and Spaces That Promote Writing

Make Yourself Write at Home: How to Encourage Your Budding Writer

M

Y PROFOUND

appreciation goes to my editor, Jennifer Urban-Brown, and everyone at Trumpeter Books, for embracing a little book about learning to write, right from the start.

Thank you to my parents, who started it all.

To my mother, who (among many other things) taught me to write. She also served as a proofreader, consultant, and writing role model. Most of all, returning a favor, her confidence in me shamed me into completing this book.

To my father, who (among many other things) taught me to fish. Although seemingly unrelated, the many hours we spent honing the art of baiting hooks, casting out, waiting patiently, untangling lines, and having faith prepared me for the craft of writing a book (and for life). Though we never caught much, I sure learned plenty.

Thank you to everyone else, who kept me going.

To my sisters, Maria and Megan, who are relentlessly supportive and have never let me down.

To my dear friend Regina Bast, who listens to my chatter and tolerates my quiet with incomparable grace and understanding.

To Elizabeth Eskanasi and Rya Levin, my first readers (and cheerleaders). To Renee Lockhart, whose persistent question, “How can we be most effective?” has become my touchstone. To Nora Strecker, who shares gentle wisdom on publishing, parenting, and life. To Allison Gillis of

Wondertime,

for graciously initiating me into the real world of writing. To Christina Katz, who provided pitch-perfect advice. To the online community of bloggers and blog readers, some of the most intelligent and creative people I’ve never met. And to all the children I’ve worked with, who have been my wisest teachers.

I give thanks

and

my heart to my children, my reason to be. To my son, Jack, who has been with me every step of the way, learning with me, inspiring me, and harboring unwavering faith in me. And to Gracie, for devoted lap warming and back patting (while also nursing her own editorial aspirations by marking up my manuscript and reorganizing my pages).

Above all, I thank my husband, Bruce, without whom, nothing.

From Scribbles to Script

M

Y INTEREST IN TEACHING

parents about writing-skill development started, like many things do, as a burning desire to solve a problem. As a young, go-getting occupational therapist, I consistently had a full caseload (and ever-growing waiting list) of children ranging in age from preschool to middle school. All of these children qualified for occupational therapy services, meaning that they demonstrated some measurable delay in their ability to perform age-appropriate developmental tasks. As a pediatric occupational therapist, it is

my

daily job to help kids master the skills they need to be successful at all of

their

daily jobs. To accomplish this, I do my best to combine everything I know about the science of child development with the art of creating the just-right activity for each child’s individual needs.

I was an itinerant therapist, which meant I traveled all around the neighborhood to see kids in their various environments, including home, school, and clinic settings. I had a car full of toys and tools, and lugged a giant tote full of gear into each appointment. The specific issues each child was experiencing varied. Yet one thing remained consistent across the board: every child I saw struggled with writing. Their teachers knew it, their parents knew it, and, most important, they knew it. From preschoolers who struggled to scribble, to middle schoolers who struggled with script, writing problems were plentiful. And although I loved every minute of working with these kids, a nagging question followed me to each stop. Why are there so many reluctant writers?

Every day as I worked, the question resurfaced. When it comes to teaching these kids to write, where have we gone wrong? Slowly but surely answers emerged. They showed up in the trunk of my car, in my tote, and in my treatment activities themselves. From preschoolers to preteens, all of my kids would consistently gravitate to the same stuff. How could that be? Despite my never-ending bag of tricks and all my cleverly conceived activities, reluctant writers of all ages continued to want (and need) to go back to the basics.

So with all of my reluctant writers, big and little, we went back to the foundation. Foundational skills, that is. Both young and not-so-young kids were on the same page with me as we revisited pre-writing skills. How to hold a pencil. How to sit upright in a chair. How to use one hand as a stabilizer while the other is at work. How to memorize the movements that make up each letter of the alphabet. We worked on hand strengthening, postural control, and eye-hand coordination. We even got down on the floor, crawling, to build shoulder stability, literally approaching the task of writing from the ground up.

And as we focused on the skills that support writing, a funny thing happened. My reluctant writers actually

wanted

to write. And, oh, the stories that came out! All of a sudden there were jokes and silly signs, letters to grandparents, love notes to Mom, diagrams for Daddy, and essays for school. When they began to crack the code of writing, it was as if they had gained a whole new voice, and a wealth of ideas to go along with it. Not to mention the confidence that comes along with mastery.

Now the concept of establishing a strong foundation was something I could really wrap my head around. As the daughter of an architect, this is something that was impressed upon me from a young age. I’ll never forget the day when my dad came to my kindergarten class for career day (wearing his hard hat and carrying a set of blueprints) and asked the class the all-important question, “What’s the

first

thing you need to build a house?” All of us wannabe builders promptly called out: “A hammer!” “Nails!” “Wood!” “Walls!” “Windows!” “A door!” “A roof!” But one boy sat quietly, hand raised high, and waited for my dad to call on him. “A hole,” he said with conviction. And although the children broke out in laughter, my father beamed. “Yes, John,” he nodded approvingly, “to build a house you must start with a hole.”