The Year Money Grew on Trees (12 page)

Read The Year Money Grew on Trees Online

Authors: Aaron Hawkins

The next three days it rained and even sprinkled during the night. It made working outside so muddy that we called it quits after an hour. Everyone was thrilled. I was thrilled it had stayed above forty degrees.

***

On Thursday morning the sky was a deep blue, and the moment I stepped outside I could tell the temperature had dropped. We were able to get back into the orchard that afternoon, but I was terrified at what might happen during the night.

"What do they say the temperature will be?" I asked my dad later, not daring to look at the TV.

He saw my worried face and hesitated. "They said thirty-one, son, but I don't want you to get all worked up. They're hardly ever right, and we're usually a couple of degrees warmer than Farmington."

I tried to sleep but kept popping out of bed to pace the floor between my door and window. Every hour or so, I tiptoed into the kitchen and called the phone number that reported the time and temperature. At 3:30 a.m., the voice said thirty-two degrees. I prayed some more. I felt absolutely helpless. I wished I had three hundred blankets or tarps to wrap around the trees. Why had we picked up those branches? We could have made bonfires to warm up the whole place.

My mom had to come and wake me up the next morning, and I could feel I had bit my lip raw. At school

I could barely keep my head off the desk. When I got home, I scanned the local paper looking for the overnight temperature. It listed thirty-one.

"What's wrong?" asked Amy as I joined my cousins in the orchard. "You look like you're going to throw up."

"Nothing!" I said, trying my best to appear cheerful. I didn't want everyone else worrying and giving up. For the rest of Friday and all of Saturday, I kept fairly quiet and a couple of trees ahead of the others, knocking manure off the biggest weeds and then attacking them with my shovel. I was thinking of what I would say to everyone if I had to break the news about a frozen crop. There had been more and more blossoms blooming every day, so that every tree looked like it was coated in pink snow. I had no idea if this was a good or bad sign.

It was late afternoon, and the others were discussing whether or not you could be killed by a bee's sting as bees buzzed around our heads. "...I'm just telling you what my teacher said. Some people are extra allergic, and even one sting can kill them," stated Lisa matter-of-factly.

"But bees don't sting as bad as black widows, and even they won't kill you," replied Sam.

Amy wasn't paying attention and was singing along to Duran Duran on the radio.

"Why don't we call it a day?" I announced.

"Really? Already?" asked Lisa.

"Why? Aren't we going to finish the other trees?" asked Jennifer.

"Yeah, but you've been working so hard that I think you deserve a break," I explained.

"Sounds good to me," said Amy, throwing down her hoe but giving me a squinting stare.

Something in me couldn't go on anymore without knowing.

***

Before church the next day, I wandered through the orchard examining branches. They were still covered in blossoms, but I didn't know the difference between a live blossom and a frozen one. I shook a few trees to see if anything fell off. The pink petals hung on stubbornly.

As soon as Brother Brown came into our Sunday school class, I got up and walked toward him. "Did they make it?" I asked very seriously. I could see he instantly knew what I was talking about. I could feel the worry written all over my face.

The side of his mouth raised up as if involuntarily starting to grin. "Well, I think they pulled through."

"Really?" I replied breathlessly. I wanted to shake his hand or hug him. Instead, I sat in the seat closest to where he was standing.

***

The temperature rose steadily after that week, rarely dipping into the thirties again. The blossoms eventually fell off the trees in a great shower that covered the ground in pink. They left tiny round balls behind that were the start of apples.

Their appearance made the orchard feel more serious, as if spring's allusions were over and the real business of growing had begun. Our work felt more serious too. If the trees and weather hadn't cooperated, we could have quit then and there. My sisters and cousins would have felt gypped, but I wouldn't get all the blame. Now the expectation of a payoff began to grow with the apples. There was no going back, and someday soon my promises were going to come due.

Water, the Free and Dangerous Kind

The New Mexico state flower is the yucca. A yucca probably has more in common with a cactus than it does with an everyday flower. It grows long, needle-sharp leaves that stick out like a porcupine's quills. From the middle of these a tall stem grows, decorated with yellow petals.

When you grow up in New Mexico, just like the yucca, you rarely have access to much water. If left alone, most of the land would look like our plot of desolationâdirt, rocks, and tough weeds. You start seeing the world in browns and reds.

The area surrounding our house was mostly those colors except right near the front door. My mom had planted a little patch of grass she called her "touch of civilization." It was only about fifteen by fifteen square feet, but my dad wouldn't let it get any bigger because it had to be watered with city water that came from the tap. We were repeatedly reminded 'that they charged by the gallon for that stuff'.

Not all of the area around Farmington was desolate. The San Juan River brought some of it to life. People had been irrigating for decades by pulling water out of the river with canals. Wide swaths of the valley between the river's plateaus were green with fields of alfalfa, beans, and corn.

The nearest canal to our house was on the opposite side of the road that led to FarmingtonâState Highway 550. One thing the library's apple book had made clear was that an apple tree needed lots of water. I knew that Mr. Nelson must have used water from that canal if he had ever gotten anything to grow, but I had no idea how he'd done it. In fact, since I could walk, I had always been warned to stay away from the canal. In my mother's eyes, it was nothing but a baby killer that could sweep away and drown her kids.

As the weather grew warmer, I knew we had to get some serious water on the trees. This meant figuring

out the canal and irrigation. I went through my usual progression of adult advisors.

Mrs. Nelson simply said, "I know my husband used to go across the road to turn the water on. He used to always wear big rubber boots and take a shovel."

My dad said, "If you can figure it out, let me know 'cause I'd like to use some on this yard. Something besides these weeds might class things up a little."

***

Again I found myself in Sunday school staring at Brother Brown. After the close call with the blossoms, our joint worrying had brought us together somehow. At least I felt that way about him. It was still unclear how he felt about me.

I cornered him after class, blocking his way to the door. "So how are your trees doing?" I began.

"Fine," he answered, trying not to look at me.

"Brother Brown, when is it time to start watering them? You know, with irrigation?"

He seemed a bit amused. "Is there water in the canal?"

"Ummm, I don't know."

"Well, you can't water without water."

"When there's water in it, do you think I could come watch you, you know, irrigate?"

He thought about this a long time. "We'll see when there's water."

I thought that sounded pretty hopeful. A "we'll see" was getting pretty close to a "maybe," and with my dad at least, that wasn't far from an "okay."

***

After school the next day, I jumped off the bus and announced to everyone, "I'm going over to check the canal. Who wants to come with me?"

Sam's and Michael's eyebrows went up. Lisa's eyebrows went down. Amy kept walking toward home. After assuring Lisa that we were on official orchard business and she shouldn't tell Mom, Sam, Michael, and I dodged traffic and crossed the road.

We climbed the embankment that hid the canal. The canal banks were thickly crowded with little trees and weeds, so it was hard to see if there was water flowing or not. We inched our way down the bank through the screen of plants until we reached a dry bottom. No water yet. Sam and Michael began wandering down the length of the canal.

"We better go, you guys," I called out. "We don't want to be down here if the water turns on." My accumulated years of warning had begun to make me nervous.

***

We repeated our canal inspection on Tuesday and still found it dry. On Wednesday, however, muddy water was flowing six feet deep and ten feet wide.

"It's on! It's on!" I yelled at my cousins.

"Now what?" asked Sam.

"I dunno. We're going to need some serious help."

That night I grabbed the phone book and turned the pages toward the

BROWNS.

"Mom, do you know Brother Brown's name?" I called to her.

"You mean your Sunday school teacher?"

"Uh-huh."

"I think it's Jess or Jessie."

I looked through the list. There was only one Jess. I read out the number to my mom.

"Does that sound right?"

"How should I know?" she replied.

I grabbed the phone, untwisted the long cord, and dialed. I half hoped it was the wrong number.

"Hello?" said a woman's voice on the other end.

"Um, is Brother Brown there?"

There was a pause, then, "Yes, I'll get him." It seemed like a whole minute went by.

"Yeah, hello?" said a recognizable, croaky voice.

"Hello, Brother Brown, this is Jackson Jones from your Sunday school class." I paused, but he didn't say anything. "I saw that the canal water got turned on today, and I was wondering if I could come over and watch you irrigate. Like we talked about."

There was a long silence. "When would you want to come?" he finally asked.

"Anytime that's good for you. Oh, wait, no, I guess it would have to be after school. Say, four o'clock."

"Well ... I guess so. Be here tomorrow."

"Thanks. Thanks a lot. I'll see you tomorrow."

I hung up the phone excitedly. I ran and told Amy and the boys about the special training and how I thought we should all be a part of it.

"How are we supposed to get there?" asked Amy.

"Ride the tractor," I suggested. She groaned, but the boys liked the idea. I also told Lisa and Jennifer that we had to make a special exception and they needed to come along even if it was a school night.

"Think of it as kind of like a class. Or a field trip. Whatever you feel best about," I explained.

"I don't feel good about either one," grumbled Lisa.

***

Amy drove the tractor the next day because she said it was better than riding in the wagon. We pulled up into Brother Brown's yard and saw him walking toward us. I jumped out of the wagon while everyone piled out behind me. "Brother Brown," I called cheerfully, "I brought my whole work crew with me."

Amy gave me a dirty look while Brother Brown inspected us and grunted a little. He was wearing blue biboveralls, and he looked more relaxed than he ever did at church.

"Let's go, then," he said, and gestured toward the nearest trees.

We followed him in single file, walking past a large, brightly painted green tractor.

"I like your tractor, Brother Brown. It's a John Deere right?" called out Sam.

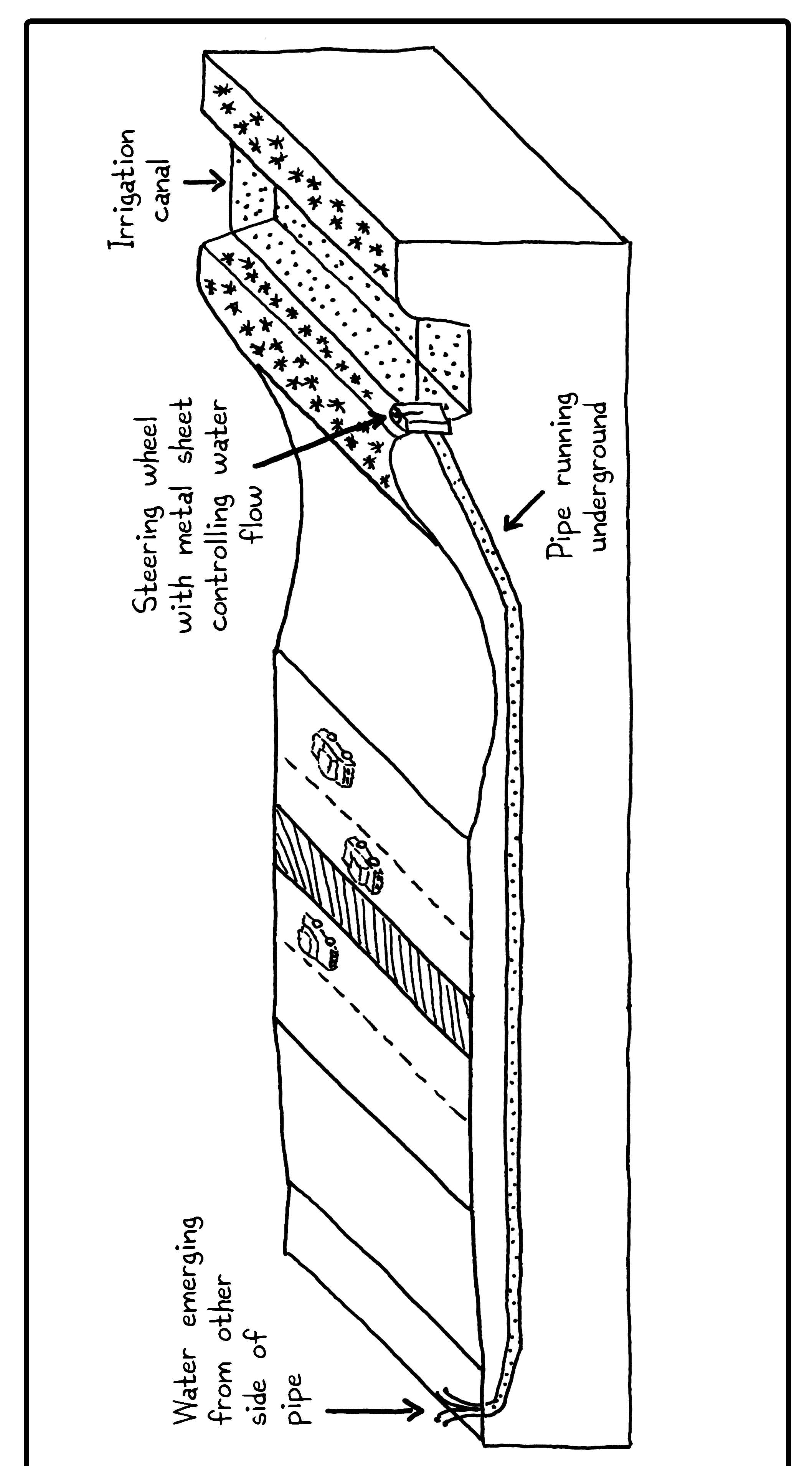

Brother Brown turned his head slightly to see who had spoken but didn't say a word in return. We tunneled through a part of his orchard. The trees were about the same size as ours, but the rows much longer so that when you were in the middle of one, you began to lose your sense of direction. We emerged near the highway and then followed Brother Brown across. He climbed the canal embankment and found what looked like a steering wheel attached to a long screw. The screw ran down into a cement wall built into the side of the canal. Brother Brown began turning the steering wheel, which raised a sheet of metal built into the cement.

"Uh, whatcha doin'?" I called to him from a little way up the canal's bank.

"Gotta open the ditch," he said, and kept turning.

With each twist of the wheel, the metal sheet rose higher and water began rushing into a smaller ditch perpendicular to the canal. When the gate was all the

way up, a healthy stream of water had filled the ditch, flowing toward the road and disappearing.

"Where's the water going?" I asked Brother Brown.

"Pipe under the road carries it to the other side," he said as he climbed the canal bank and started walking toward his orchard.

"Does everyone have a gate and a wheel like that?"

"Everyone who can get water."

"How can I find the one for our orchard?"

"Better start lookin'."

We crossed the road directly across from Brother Brown's wheel. Next to his last row of trees, water was pouring out of what looked like a hole in the ground. It filled a deep ditch that ran parallel to the road. We followed Brother Brown past ten rows of trees until we came to a tarp that had been set across the ditch and held in place by rocks.