The Year Money Grew on Trees (2 page)

Read The Year Money Grew on Trees Online

Authors: Aaron Hawkins

I kept nodding my head and trying to seem interested.

"You know, when Tommy was about your age, his father tried to get him to help out with those trees, but he

was always happier doing something else, anything else." She shook her head. "How old are you now, Jackson? Fourteen, fifteen?"

"I'll be fourteen in a few weeks," I mumbled.

"In a lot of ways, you remind me more of my husband than Tommy does. The way you always like to be outside and working with your hands."

I gave her a halfhearted grin to acknowledge the compliment. Being outside all the time was mostly due to my mother's policy on not overcrowding the house rather than a conscious personal choice. As for working with my hands, Mrs. Nelson was probably referring to all her yard work she had cornered me into doing. She looked above my head like she was trying to see something off in the distance. Then she began talking quietly to herself as if I weren't in the room.

"I just hate to see it neglected like that. It breaks my heart to think that Tommy would just dig up those trees. Probably put a trailer park over it or something. Serve him right if I gave it to someone who'd keep it up." All of a sudden she lowered her eyes and stared me into blushing. "How about you? How'd you like that orchard?"

"Uh ... m-me? What would I do with it?"

"Raise apples, of course. That's the whole point. If you do it right, you can make plenty of money too."

That last part caught my attention, and I sat up a little

straighter. "But why me? I don't know anything about apples."

"I just need someone willing to learn. Someone who can prove they'll take care of the place when I'm gone."

"How would I prove that?"

Mrs. Nelson leaned back like she was thinking. "You could work on it this year and give me a chance to examine the results. Then I'll decide."

The idea of her giving me the orchard sounded pretty meaningless to thirteen-year-old ears. Why would I want the thing? The interesting part in what she was saying was the possibility of making some money. "What about the money, if, you know, there were some apples that were sold?"

Mrs. Nelson got a distasteful look on her face. "Money. Well, yes, I guess you could have some of the money, depending on what kind of job you did. The same kind of arrangement we make when you work in my yard."

My heart sunk. The "arrangement" we had with her yard was that she would promise me $5 for something that supposedly took only a couple of hours. After an entire Saturday of breaking my back for her, she'd hand me a dollar bill and say my work wasn't up to $5 standards. Once she even sent me home without the usual dollar because I pulled up hydrangeas I thought were weeds. She'd screeched like I'd killed a bunch of puppies.

I'd never learned to say no, however, and gotten suckered into the same thing dozens of times. The orchard sounded like an even bigger con job. I'd probably work every day for a year, make her a bunch of money, and then she'd hand me a dollar bill. "Not up to $5 standards," she'd say. "And I'm giving the orchard to someone else now that it's all cleaned up." I looked down at my feet and didn't say anything.

"What do you think? You willing to take over for my husband? Make those trees come alive again?" Mrs. Nelson asked insistently.

"I'll have to think about it," I replied slowly. That was the answer my dad gave to all salesmen. He said that was standard practice no matter how much you wanted something or how good the deal seemed. This deal didn't seem that good, and I really would have to think about it.

"Think about it?" asked Mrs. Nelson, acting very put out. "Well, don't think too long. Opportunities like this come along once in a lifetime. People don't just go around giving away land and orchards."

I thanked her for the cocoa and got up to leave. I remembered to tell her I was sorry to hear about the cancer and hoped she felt better. After a few sighs and dramatic sniffles, she walked me to the door. "I expect to hear back from you right away about the orchard," she called as I hurried around the corner of her house.

When I walked in my front door, my mom didn't seem to notice it had taken me an extra long time to return from the bus stop. I didn't dare mention the orchard proposition to her or to my dad when he got home. They had always seemed to avoid and distrust Mrs. Nelson. Somehow she had singled me out as the one person in our family she would talk to, but only if she caught me walking along the dirt road past her house. Since I knew her better than anyone and I'd be doing all the work, I felt like I could make a decision about the orchard on my own. The idea made me feel anxious but grown-up. By the time dinner rolled around, I had convinced myself that the smartest thing to do was to ignore Mrs. Nelson and let her plan fade away. It seemed like just a crazy impulse she'd had, anyway.

My family sat down to eat with my mom and dad at either end of the table and my two little sisters sitting across from me. Dad had on the usual worn-down expression he wore after work, and he was still wearing his denim work shirt. My mom pointed out two of his favorite dishesâscalloped potatoes and pot roastâand then began cheerfully filling up plates. Dad grunted his appreciation.

"I stopped by the scrap yard on the way home," Dad announced after taking a few bites. "Talked with ol' Slim Nickles. He says he gets really busy during the summer and needs extra help. Just manual labor kinds of things,

no skills required. I told him I had a son who didn't have any skills but could probably haul things around. Slim said we could stop by and he'd look you over." Dad finished by pointing his fork at me.

I let my fork drop on my plate and my mouth hang open. The scrap yard was on the side of the highway Dad took to work, and he loved stopping in and searching through the mounds of metallic junk. He'd stop in on Saturdays, too, and drag me along. I couldn't stand the place. It was filthy and smelled like burning rubber. And Slim Nickles was the biggest jerk I'd ever met. He was usually covered in grease and had a wide red face and a huge gut. He yelled every word he said and loved to intimidate people. The one time he'd noticed me, he warned me to keep my hands in my pockets or he'd snap them off.

Before any sounds of protest could come from my mouth, Mom spoke up. "He's only thirteen. Are you sure he's old enough to have a job?"

"He'll be fourteen this summer. When I was fourteen, I was working as much as a grown man, maybe more," replied Dad, his voice getting louder.

Mom rolled her eyes. "Are you sure that's going to be a safe place for a boy to work?"

"It'll be safe enough. As long as he's not just sitting around the house like last summer. Any more of that and he'll be a freeloader the rest of his life."

"Oh, Dan," Mom said. "Don't sound so mean. You're going to give your own son a complex."

"I'm just trying to do what's best for him. My dad never let me just lay around."

"I'd be happy to have a job," I broke in, "but does it have to be at the scrap yard?"

"I don't care where it is, but you'll have to find someone who'll hire a fourteen-year-old. Slim's the only one I know."

The orchard popped into my head, but I didn't want to say anything about it. My mind raced through other potential employers anywhere near my house. "What about that snow-cone stand by the school?"

"That guy's got all his kids working there. Nah, this weekend we'll go talk to Slim and get things lined up."

I stayed quiet the rest of dinner, stewing about the scrap yard. If I put up a big fight and refused to go, my dad would make life at home miserable. And if I went along with him, Slim would be more than happy to make my time away from home miserable. Either way, I was bound to be miserable. I had to find something else, almost anything else.

Saved from the Scrap Yard

In only a matter of hours, my life had accelerated uncontrollably. My only worries had been homework and girls, but all that seemed in the distant past. My future depended on a choice between two terrible jobs I didn't need. I realized I didn't want to feel grown-up anymore.

I hadn't decided anything until lunch at school the next day. I watched Slim's son Skeeter cut in the cafeteria line and then punch the kid behind him who protested. Skeeter was a grade ahead of me but a couple of years older. He was built like his dad and maybe even meaner. The proudest moment of his life was when he

made a substitute teacher run out of his class crying. While the sub was gone, Skeeter lit the garbage can on fire and then peed it out, bragging he was "saving the class."

I stared at Skeeter and realized he'd be at the scrap yard all summer too. Maybe he'd even be my boss. That afternoon I knocked on Mrs. Nelson's door right after getting off the bus.

"Ah, Jackson. I thought you'd be back," she said when she answered the door. "Why don't you come in again?"

I shuffled over to the same chair I'd sat in the day before. Mrs. Nelson sat across from me again looking more composed. The tears were gone and all her hair was neatly in place.

"I've been thinking about the orchard," I began, "and I think I'd like to do it. There's just one little thing."

"Oh? What's that?"

"Could we maybe agree on a way to split the money from the apples? Say, you get a certain percentage and I get a certain percentage?"

"You're still worried about the money, are you? Remember, that's not what's important to me. I could just go hire anyone off the street if I wanted to make money. After you left yesterday, I realized I was really looking for the orchard's true heir." She said that last sentence as if she were reading from a book of fairy tales.

I wasn't sure what to say about the "true heir" stuff.

All I wanted was to get some number or percentage out of her mouth. "I promise to work super hard. But maybe if I had a goal to shoot for, it would help keep me going."

"I told you I'd take care of you. You'll get rewarded according to how you work."

"Yes, but if there was just something specific, I think it would be better. You know, if I do this and this, then you do that."

"Ah, don't you trust me? Think I'm not really serious?"

"No, it's not thatâit's just..."

"Fine. Let's be specific," she said, cutting me off. "You get that orchard running and pay me a certain amount, and then you can have the rest of the money and more importantly the orchard."

"Okay," I said cautiously, "how much?"

"Let's see," she said with a look of disgust on her face, as if the very thought of money was repulsive. "From what I remember my husband making, I'd say $8,000 would be about right."

"Eight thousand dollars? That's impossible!" I gasped almost involuntarily. I hadn't imagined making even a tenth of that.

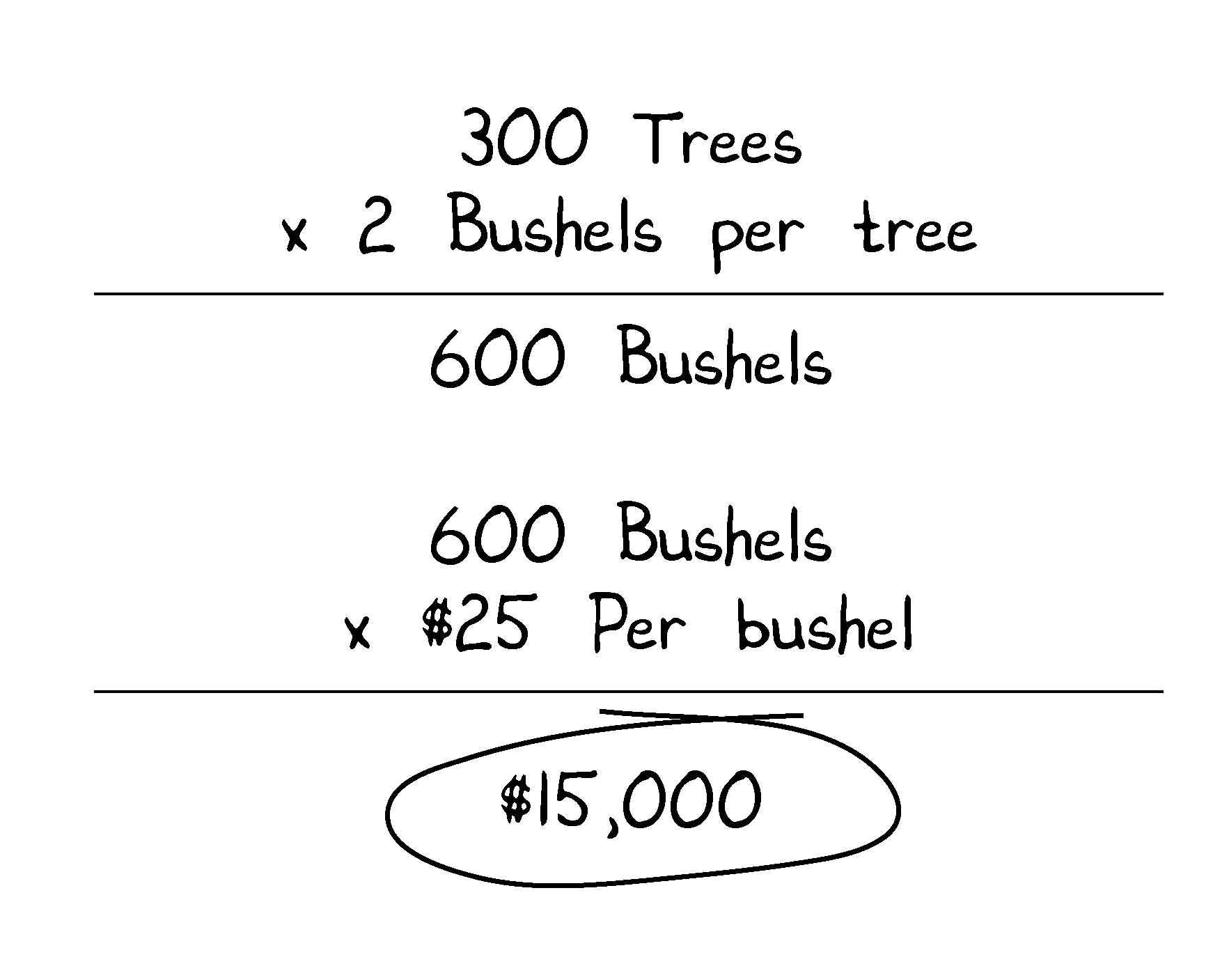

"Impossible? You're thinking like a child. There are 300 trees out there. They'll each produce several bushels, and at the grocery store a bushel of apples is $25 or more.

That's a lot more than $8,000. It's practically like growing money on trees."

I roughly did the math in my head, and it came out to almost twice $8,000. I wasn't 100 percent sure of her or my math, but if the numbers were right, I'd make plenty of money plus whatever the orchard was worth. "It would be a lot of work, though," I finally said.

"It's supposed to be. I'm looking for the true heir, remember. If you do that much work, I'm sure you'll want to keep watching over those trees."

There she went with the "true heir" stuff again. It still sounded like there was a good chance I wouldn't get anything. "I don't understand why we can't just split the

money, and then you can decide whether you want to give me the orchard or not."

"It doesn't matter if you don't understand. I understand and it's my orchard and I'm going to do what's best for it." Her voice got higher and took on a tone that meant I shouldn't argue. I could tell I was getting pushed around, but I had nowhere else to go.

"I guess it will be all right, then," I said quietly. "I'll just have to make that $8,000 somehow." I was mostly talking to myself, trying to quiet all the doubts raging through my head.

"We're agreed, then," Mrs. Nelson said, smiling for the first time.

"Shall we shake hands on it or something?" I asked sheepishly.

"I've got a better idea. Let's put it in writing. I've got a lawyer in town working on my will. We'll have him write something up. I told Tommy about our plan this morning, and he said I'd never do it. I can't wait to show him a written contract." A vindictive grin spread over her face. "We can still get there before the lawyer leaves for the day."

"Now? Go now?"

"Yes, now. Let me get my coat."

Mrs. Nelson stood up and I followed her. "Let me just run home and tell my mom," I said, a little dazed.

"Right, right. I'll meet you out at my car."

Mrs. Nelson didn't seem like the type of person to do things on the spur of the moment, so it was surprising to see how determined she was to act immediately. I wasn't about to argue, however, so I ran home and found my mom. She was talking on the phone, but I cut in.

"Mrs. Nelson needs me to go to Farmington with her. Needs some help with something," I said, out of breath.