The Year of Shadows

Read The Year of Shadows Online

Authors: Claire Legrand

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #General, #Social Issues, #Friendship, #Action & Adventure

For the music teachers, mine and everywhere—

—and for Mom, my anchor

Acknowledgments

This is, for many reasons, a special book to me. My own experience as a musician is one of these reasons (I used to be a trumpet player, but I was not much of a charmer); my mom’s bout with cancer, which colored the writing of this book, is another. I therefore have many people to thank:

First, for her unwavering support, keen insight, and priceless phone chats, my agent, Diana Fox; my brilliant and enthusiastic editor, Zareen Jaffery, who asks all the right questions; the whole team at Simon & Schuster, especially the ever-helpful Julia Maguire, Lydia Finn and Paul Crichton, Katrina Groover and Angela Zurlo (oh, so many thanks for your fine-toothed combs!), Bernadette Cruz, Michelle Fadlalla; art director Lucy Ruth Cummins, for making my books look beautiful; Karl Kwasny, for his delightful illustrations; and Pouya Shahbazian and Betty Anne Crawford, for spreading the word.

To my writer friends, inspiring and encouraging—Alison Cherry, Lindsay Ribar, Lauren Magaziner, Tim Federle, Leigh Bardugo, Trisha Leigh, Emma Trevayne, Stefan Bachmann, Katherine Catmull, Ellen Wright; the Apocalypsies, for their relentless support; and especially to Susan Bischoff and Kait Nolan, writerly soulmates. To the bloggers, librarians, fellow writers and readers, to Twitter and Tumblr and all the online bookfolk who make the

day-to-day fun and offer such lovely support—thank you.

I would not be who I am today without my musical background, so I must give the warmest thanks to a few special music teachers over the year—Kristen Boulet, John Light, Irene Morris, Asa Burk, J. R. Stock, Nicholas Williams, Dennis Fisher, Maureen Murphy, Mike Sisco, Ellie Murphy, Marty Courtney, and John Holt, all of whom challenged and inspired me. Thank you to Andrew Justice, Maureen Murphy, and Jonathan Thompson, for helping me program the City Philharmonic’s season. Special thanks must go to the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Maestro Jaap van Zweden, in whose beautiful music hall I first saw Olivia and Igor; and to Ryan Anthony, trumpeter extraordinaire and Richard Ashley’s real-world namesake.

To Dr. Alan Munoz—“Dr. Birdman,” to Olivia—and the staff at Medical City Hospital in Dallas, for taking such good care of my mom; to my friends and family, especially those who helped us through dark times—Pati Gann, Judy Roumillat, Pat Peabody; to Battleship Legrand—is it Destin time yet?!—to Ashley, Andy, my wonderful stepmom, Anna, and my unstoppable dad, W. D., all of whom I miss every day; to my dear friends Starr Hoffman, Beth Keswani, Melissa Gann, Brittany Cicero, and Jonathan Thompson—my rocks, my lifeboats; and to Matt, my love, master untangler of plot knots.

Lastly, to Drew, and to Mom—thank you, miss you, I love you. We made it.

PART ONE

T

HE YEAR THE

ghosts came started like this:

The Maestro kicked open the door, dropped his suitcase to the floor, and said,

“Voilà!”

“I’ve seen it before,” I said. In fact, I’d basically grown up here, in case he’d forgotten.

“Yes, but take a look at it. Really look.” He said this in that stupid Italian accent of his. I mean, he was full Italian and all (I was only half), but did he have to sound so much like an Italian?

I crossed my arms and took a good, long look.

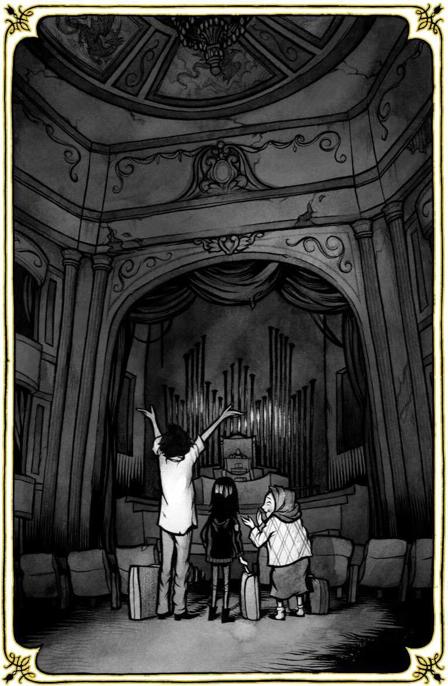

Rows of seats with faded red cushions. Moth-eaten curtains framing the stage. The dress circle boxes, where the rich people sat. Chandeliers, hanging from the ceiling that was decorated with painted angels, and dragons, and fauns playing pipes. The pipe organ, looming like a hibernating monster at the back of the stage. Sunlight from the lobby behind us slanted onto the pipes, making them gleam.

Same old Emerson Hall. Same curtains, same seats, same dragons.

The only thing different this time was us.

And our suitcases.

“Well?” the Maestro said. “What do we think?”

He was on one side of me, and Nonnie on the other. She clapped her hands and pulled the scarf off her head. Underneath the scarf, she was almost completely bald, with only a few straggly gray hairs left.

The day Mom disappeared about nine months ago, just before Christmas, Nonnie had shaved all her hair off.

“Oh!” Her wrinkled face puckered into a smile. “I think it’s beautiful.”

My fingers tightened on the handle of my suitcase, the ratty red one with the caved-in side. “You’ve seen it before, Nonnie. We all have, a million times.”

“But is different now!” Nonnie twisted her scarf in her hands. “Before, was symphony hall. Now, is home.

È meglio

.”

I ground my teeth together, trying not to scream. “It’s still a symphony hall.”

“Olivia?” The Maestro was watching me, smiling, trying to sound like he really cared what I thought. “What do you think?”

When I didn’t answer, Nonnie clucked her tongue. “Olivia. You should answer your father.”

The Maestro and I didn’t talk much anymore. Not since Mom left, and even for a couple of months before that, when he was so busy with rehearsals and concerts and trying to save the orchestra by begging for money from rich people

at fancy dinners that he wouldn’t come home until late. Sometimes he wouldn’t come home at all, not until the next morning when Mom and I were in the kitchen, eating breakfast.

Then they would start yelling at each other.

I didn’t like breakfast much after that. Every time I looked at cereal, I felt sick.

“He’s not my father,” I whispered. “He’s just the Maestro.” I felt something change in that moment. I knew I would never again call him “Dad.” He didn’t deserve it. Not after this. This was the last straw in a whole pile of broken ones.

“

Ombralina

. . . ,” Nonnie scolded.

Ombralina.

Little shadow. It was her nickname for me.

The Maestro stood there, watching me with those black eyes of his. I hated that we shared the same color eyes. I could feel something building inside me, something dangerous.

“I think I’m going to throw up,” I announced.

Then I turned and ran outside, my suitcase banging against my legs. Out through the lobby, past the curling grand staircases and the box office window, and onto the sidewalk. Right out front, at the corner of Arlington Avenue and Wichita Street, I threw down my suitcase and screamed.

The traffic sped by—cars, trucks, cabs. People pushed past me—office workers out for lunch, grabbing sandwiches, talking on their phones. Nobody noticed me. Nobody even glanced my way.

Same old Emerson Hall. Same curtains, same seats, same dragons. The only thing different this time was us. And our suitcases.

Since Mom left, not many people noticed me. I wore black a lot now. I liked it; black was calming. My hair was long, and black too, and shiny, and I wore it down most of the time. I liked to hide behind it and pretend I didn’t exist.

I couldn’t decide if I wanted to cry or hit something, so I turned back to Emerson Hall’s double oak doors. Stone angels perched on either side, playing their trumpets. Someone had climbed up there and spray-painted the angels orange and red. I squinted my eyes, trying to imagine the Hall’s blurry shape into something like a home. But it didn’t work. It was still a huge, drafty music hall with spray-painted angels, and yet I was supposed to live here now.

“Might as well go back in.” I kicked open the door as hard as I could. “Not like there’s anywhere else to go.”

Our rooms were two empty storage rooms backstage: one on one side of the main rehearsal room, and one on the other side. There was also a cafeteria area with basic kitchen stuff like a sink, microwave, mini-fridge, and hot plate. It used to be for the musicians, so they could break for lunch during a long day of rehearsals.

Not anymore, though. It was our kitchen now.

The Maestro, Nonnie, and I hauled our suitcases backstage—one for each of us, and that’s all we had in the world, everything we owned.

The Maestro disappeared into the storage room that would be his bedroom and started blasting Tchaikovsky’s

Symphony no. 4 on the ancient stereo that had been there for years. The speakers crackled and popped. Tchaik 4—that’s what the musicians called it—was the first piece of music on the program that year. Rehearsals would start soon.

Nonnie carefully arranged her suitcase in the middle of the rehearsal room, surrounded by stacked chairs, music stands, and the musicians’ lockers, lining the walls. She perched on her suitcase and waved her scarf at me. Then she started humming, twisting her scarf around her fingers.

Nonnie didn’t do much these days but hum and twist her scarves.

I sat beside her for the longest time, listening to her hum and the Maestro blast his music. I felt outside of myself, distant and floaty, like if I concentrated too hard on what was happening, I might totally lose it. The tiny gusts of ice-cold air I kept feeling drift past me didn’t help.

Great,

I thought.

It’s already freezing in here, and it’s not even fall yet.

This couldn’t be happening. Except it was.