The Young Desire It

PRAISE FOR

THE YOUNG DESIRE IT

âThis story of a boy's first love is one of the truest and most beautiful things that has been written by an Australian.'

West Australian

âA first novel of exceptional interest and originality. Few characters in fiction have been more completely or beautifully portrayed.'

Spectator

âA frank plea for the freedom of youthâ¦In this penetrating first novel Mackenzie proves himself to be a writer of outstanding ability.'

Mail

(Adelaide)

âAmazingly brilliant.'

Liverpool Daily Post

âA beautifully written story of a sensitive boy's movement towards adult love.'

Sydney Morning Herald

â

The Young Desire It

presents the adolescent boy's view with power and poignancy.'

The Times

âIt transcends by its sincerity and freshness the bonds and difficulties of its genre and subject.'

Bulletin

âSensitive, vital and erotic.'

VERONICA BRADY

,

Australian Dictionary of Biography

âEvokes the hot Western Australian landscape with rare forceâ¦A pastoral charged with the awakening of desire, like spring.'

DOUGLAS STEWART

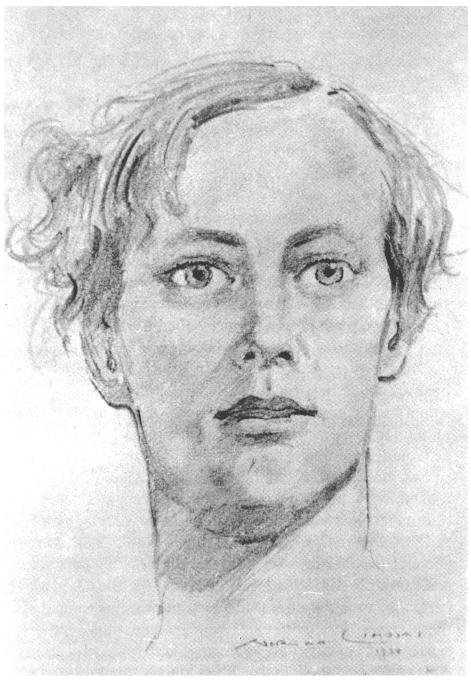

KENNETH IVO BROWNLEY LANGWELL

â

SEAFORTH

'

MACKENZIE

was born in 1913 in South Perth. His parents divorced in 1919, and he grew up with his mother and maternal grandfather on a property at Pinjarra, south of Perth. He was a sensitive child who developed an intense love of nature.

At age thirteen Mackenzie was sent to board at Guildford Grammar School in Perth. His experiences there informed his first novel,

The Young

Desire It

, published under the name Seaforth Mackenzie by Jonathan Cape in 1937. The author was just twenty-three.

The novel drew praise from

The Times

,

Spectator

and

Sydney Morning

Herald

; the

Liverpool Daily Post

called it âamazingly brilliant'. It was awarded the Australian Literary Society Gold Medal.

By this time Mackenzie had studied law, worked as a journalist and moved to Sydney. There he met the leading lights of the literary sceneâamong them Kenneth Slessor and Norman Lindsayâand married. He and his wife had a daughter and a son.

Mackenzie's subsequent novels were

Chosen People

(1938),

Dead Men

Rising

(1951), based partly on his experience of the Cowra prisoner breakout, and

The Refuge

(1954). He also produced two volumes of poetry.

Kenneth Mackenzie's last years were spent mainly alone, in declining health and battling alcoholism, at Kurrajong in New South Wales. On 19 January 1955 he drowned in mysterious circumstances while swimming in Tallong Creek, near Goulburn.

DAVID MALOUF

was born in 1934 and brought up in Brisbane. He is the internationally acclaimed author of such novels as

The Great

World

(winner of the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and the Prix Femina Etranger),

Remembering Babylon

(winner of the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award) and, most recently,

Ransom

.

The Complete

Stories

won the 2008 Australia-Asia Literary Award.

ALSO BY KENNETH MACKENZIE

Chosen People

Dead Men Rising

The Refuge

The Young Desire It

Kenneth Mackenzie

textclassics.com.au

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © the estate of Kenneth Mackenzie 1937

Introduction copyright © David Malouf 2013

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Jonathan Cape 1937

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2013

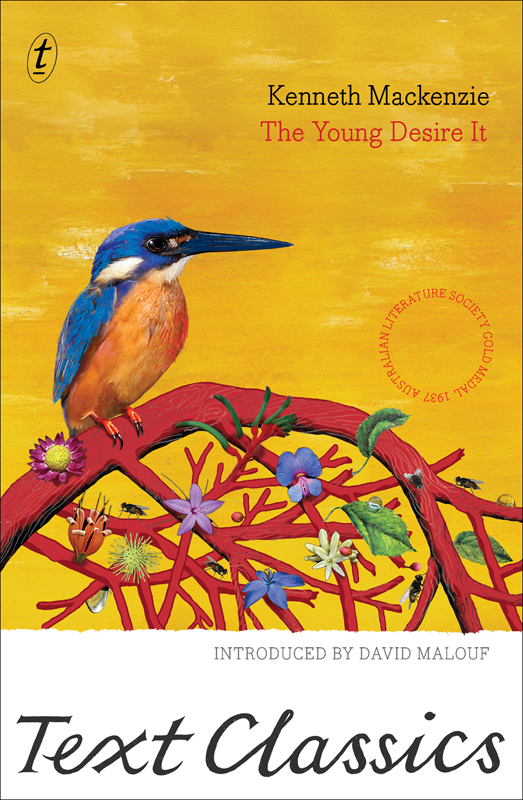

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Primary print ISBN: 9781922147509

Ebook ISBN: 9781922148544

Author: Mackenzie, Kenneth, 1913-1955 author.

Title: The young desire it / by Kenneth Mackenzie;

introduced by David Malouf.

Series: Text classics.

Dewey Number: A823.2

CONTENTS

by David Malouf

Sketch of Kenneth Mackenzie by Norman Lindsay.

© H. C. & A. Glad.

A Perilous Tension

by David Malouf

THE YOUNG

Desire It

was published in London in 1937 by Jonathan Cape. The author, Kenneth âSeaforth' Mackenzie, was not quite twenty-four. He had begun the novel at seventeen. âFive weeks of solitude,' he tells us in a dedicatory preface, âsaw the making of the whole thing.'

Like many first novels,

The Young Desire It

draws on the author's own experience. Mackenzie grew up on an isolated property south of Perth, and until he entered Guildford Grammar at thirteen shared the company only of his mother, a younger sister and a few household servants. He was left to roam, barefoot and as he pleased, in the local countryside, whose changes of light and weather he seems to have taken, like his protagonist Charles Fox, as aspects of his own nature and feelings. This accounts for the intensity of the book's nature writing, which is more disciplined than anything in Lawrence who is clearly an influence, but also more inward and passionately lyrical. Charles's first encounter with society, in the close, intrusive and sometimes threatening form of a boys' boarding school, accounts for his puzzled outsider's view of his fellow students and teachers. What is not accounted for in so young a writer is the authority with which he tackles the book's disturbing and potentially sensational material, and the assurance, in the rhythm and cadence of every sentence, of the writing. We recognise the phenomenon, but it is rare, in the precocious genius of Stephen Crane in

The Red Badge

of Courage

, in the young Thomas Mann of

Buddenbrooks

, and the even younger Raymond Radiguet of

Le

Diable au corps

and

Le bal du Comte d'Orgel

. Mackenzie and

The Young Desire It

are of that company.

The novel has two points of focus.

One is the school as a social institution: in this case an English-style, all-male boarding school in what is still, in the twenties, an outpost of empire, an establishment devoted to the making, through classical studies, music, sport, and very British notions of manliness and public service, of young men.

The masters are imported Englishmen, the students for the most part country boys who have grown up close to the Australian bush and to Australian values and traditions. They are lively and well meaning enough, but from the masters' point of view uncultivated, even when, like Charles Fox, they are also sensitive and talented. In the course of the book the whole order and ethos of the school is tested by the suicide of a wounded, yet highly effective and revered headmaster.

It is worth recalling that at this time most boys of fourteen or fifteen were already out in the world earning a living. A good part of Charles Fox's impatience to be done with school, and free, is a belief that he is being held back from life, though he also acknowledges that he knows little of what life is. He has till now been a kind of âwild child' uncorrupted by society, armed only with âa dangerous innocence' and unaware of âthe necessity for doing evil'. How he comes throughâwhether in fact he does come throughâis the book's other and major concern.

On his first afternoon at the school he is sexually assaulted by a group of older boys, on the pretext of confirming that this pretty boy is not really a girl. What Charles discovers here, as a first line of defence, is a quality in himself, to this point unknown because unneeded, that will more and more become the keynote of his emerging character. This is resistance, which over time takes different forms in him, not all of them attractive. Resistance to others, and to events and influence; resistance to his own need for affection; a growing hardness that will protect him from being âinterfered with', and allow him the freedomâit is freedom of choice that the young so ardently desireâto be himself.

Several moments of revelation mark the course of Charles's adolescent progress, some of them so deeply interiorised and undramatic as to appear, by conventional novelistic standards, unrealised: a common complaint against

The Young Desire It

is that it is a book in which, as Douglas Stewart puts it, ânothing happens'.

Another way of putting this would be to suggest that Mackenzie, in a quite revolutionary way for an Australian writer in the late thirties, is doing all he can to preserve his narrative from any whiff of the âfictitious', and himself from any temptation to the fabrications of âplot'. What interests him is not what happens in the world of events but what happens in Charles Fox's erotically charged sensory world, where he is confronted at every turn with situations for which he has no precedent. It is Mackenzie's determination to stick with the interior view, and the bewilderments of young Charles Fox, that make

The

Young Desire It

perhaps the earliest novel in Australia to deal with the inner life in a consistently modernist way. Patrick White's

The Aunt's Story

is still a decade in the future.

The most significant of Charles Fox's discoveries is his meeting, on his first vacation at home, with the schoolgirl Margaret.

Essential to this is that it happens on Charles's home ground. The mystery of the occasion is bound up with the secret, half-underground quality of the place, with low-hanging pine branches, damp pine needles, misty rain, and the fact that it is grounded in the boy's sensuous inner world means he can take for granted that what is so shatteringly âfinal' for him is equally so for the girl. It is this that makes âimpossible' for Charles the next significant moment of the book, when, back at school, Penworth, the young classics master he has formed a bond with, kisses him.

Charles has suffered a fainting fit in the school gym, at the sight of his friend Mawley's twisted ankle. When he comes to he is in Penworth's room, on Penworth's bed, with Penworth sitting on the bed beside him clasping his feet in his âbroad hands'. Confused by this but not yet anxious, he allows himself to be drawn into a discussion of his dreams, then confesses his ignorance, beyond the crude schoolboy facts, of what such dreams might mean, and of all sexual matters. The kiss that follows turns the boy's confusion to alarm. He is in no danger, he knows that. This is a proposal, not an assault, and anything beyond this is to him an âimpossibility': he has already had his revelation with Margaret which is definitive and of another kind. What concerns him is how he should act so that his response, while clearly a rejection, will also allow him to retain Penworth's affectionate interest, and Penworth his self-esteem. The man is gently reassuring: âIt's all right, dear ladâ¦Don't be frightenedâI shan't hurt youâ¦Were you frightened ofâsomething that might have happened?' But it is the boy who shows the greater care. âI may not know it all, but even if I am so young,' he tells Penworth, âI do know that you're unhappy; and if I could help I would.'