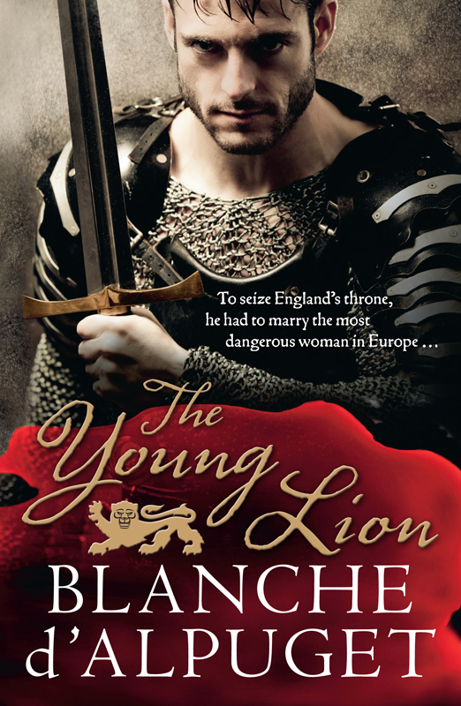

The Young Lion

Authors: Blanche d'Alpuget

MATILDA, daughter of Henry I, widow of the Emperor of Germany, wife of Geoffrey, Count of Anjou. She is the legitimate heir to the English throne

GEOFFREY ‘The Handsome’, Count of Anjou, later Duke of Normandy

HENRY, eldest son of Matilda and Geoffrey

FATHER BERNARD, monk, politician, mystic, founder of Chartres Cathedral

GUILLAUME, illegitimate son of Geoffrey and his concubine, Isabella

LADY ISABELLA, concubine of Geoffrey

LOUIS VII, King of France

ELEANOR, Duchess of Aquitaine and Queen of France, wife of Louis

XENA, Eleanor’s maid

ABBOT SUGER, Regent of France, monk and politician

BARON ESTIENNE DE SELORS, Seneschal of France

STEPHEN ‘The Usurper’, King of England

EUSTACE, Crown Prince, elder son of Stephen

WILLIAM, Prince and scholar uninterested in the Crown, younger son of Stephen

CONSTANCE, wife of Eustace and sister of King Louis

AELBAD, linguist and code-breaker for Eustace

HENRY BLOIS, Bishop of Winchester, brother of Stephen, politician, second-wealthiest man in England (after the King)

THEOBOLD, Archbishop of Canterbury

GEOFFREY THE YOUNGER, second son of Geoffrey and Matilda

WILLIAM, youngest son of Geoffrey and Matilda

DOUGLAS, Highland warrior and shaman

DAVID, King of Scotland

EARL RANULF, English magnate, supporter of King David

LADY EDITH WALTER, supporter of King David

SIR WILLIAM WALTER, husband of Lady Edith

BARON ROBERT DE CHOLET, friend of Geoffrey the Handsome

ERASMUS, Greek philosopher and physician to Eleanor

BERNARD DE VENTADOUR, Aquitaine troubadour

THOMAS OF LONDON, also known as Becket, Archdeacon of Canterbury

NATIONAL GUARDIANS IN THE SPIRIT WORLD

SAINT DENIS, Guardian of France

SAINT ANDREW, Guardian of Scotland

ANCESTORS

WILLIAM I ‘The Conqueror’, also known as ‘William the Bastard’

WILLIAM II ‘Rufus’, Elder son of William I

HENRY I ‘The Lion’, younger son of William I, father of Matilda and grandfather of ‘The Young Lion’

LOUIS VI ‘The Fat’, father of Louis VII

FOULQUES ‘The Black’, Count of Anjou, ancestor of Geoffrey the Handsome

MELUSINE, a witch, ancestress of the Counts of Anjou

LA DANGEREUSE, grandmother of Eleanor, later her stepmother, said to be a sorceress

WILLIAM IX, Duke of Aquitaine, troubadour and father of Eleanor

ANIMALS

BASTET AND SEKHMET, Eleanor’s cats

HAMBRIL, Matilda’s pet monkey

JASON, King Louis’s Arabian stallion

SELAMA, Eleanor’s Arabian mare

PRINCESS, Eleanor’s falcon

Two and a half years after leaving for Jerusalem, in the winter of 1149 the humiliated remnants of the army of the second crusade traipsed home to the Île de France. A leaden December sky made spirits sink into deeper gloom. The vanguard was ten leagues from Paris but dusk was already upon them, so the coming night would be spent in the only available accommodation, a monastery. The infantry would pitch tents in fields nearby. The cavalry would sleep in monks’ cells, the monarchs in the apartments set aside for the use of bishops.

‘It’s freezing, Princess,’ the Queen complained. She addressed the falcon she carried on her gauntlet. Through the weeks of miserable homeward travel, she’d cast the bird many times each day, whooping with excitement when it brought down a young crane or a duck. She’d schooled her favourite, a maid from Byzantium, in how to swing the lure to call Princess from the sky. But this day there had been no prey, and no excitement. Just dreary plodding through a grey winter forest. ‘Absolutely freezing,’ she muttered.

One of her knights offered to return to the sumpter horses and wagon, about an hour away, to fetch her miniver cloak. As he wheeled his horse, a rider slightly to the right of the Queen and her knights spurred his mount towards her. Approaching, he dropped

the reins, controlling his horse with his knees as he swept from his shoulders a cloak of green wool lined with soft grey badger fur.

‘Your Highness, please take it,’ he called. Her knights, men of Aquitaine and Poitou, gave him hard looks, but let him through.

The Queen passed her falcon to the maid, ripped off her gauntlet and fastened the cloak at her neck. The fur was warm from the man’s body and smelled pleasant.

‘You won’t be cold?’ she asked. Her tone indicated she did not care if he were.

‘I’m never cold, Your Highness.’ He gave her a bold, white smile and doffed his velvet hat. She noticed a sprig of broom decorated its brim. Amusing, she thought.

The knights jerked their chins at him, letting him know the audience was over and that he and his manservant, carrying his pennant of yellow leopards on a blue ground, were to fall back. Away from the Queen.

‘Find out who he is,’ Eleanor said to her maid. She had noticed him two weeks earlier, when he had first ridden over from the west to welcome home the army and the King. Many vassals were doing the same. Louis had received most of them in his tent, but there were a few he had refused an audience. Eleanor suspected her cloak-giver to be among the latter: he was vaguely familiar, for some scandal.

Xena, the maid, cantered back to the main body of the army, excited to have something to do. They were all so bored and miserable any diversion was welcome. She returned in less than an hour, her face alight with gossip.

‘He’s Geoffrey Foulques,’ she announced.

Eleanor said, ‘Ha! The Wicked Duke! I thought I recognised those leopards. He captured Normandy from the English and the Vexin from us. When he came to court to do homage for Normandy, Louis wanted to kick his head.’ She gave a delicate snort. ‘Not that my husband would be so undignified.’

Glancing at Xena, she added, ‘You’re wearing your enigmatic face, my lovely. There’s something else, isn’t there?’

Xena had skills as a beautician and she could write – unusual for a woman, even among the nobility. Observing her talents, Eleanor had pressed the Empress of Byzantium to give her the girl.

‘I paid a fortune for that little Greek,’ the Empress had declared. She didn’t want to part with her slave’s nimble wit and fingers. ‘Her writing —’

Eleanor cut her off. ‘My dearest, as Christian women we must allow this poor child to follow her dream to reach northern Europe and visit the shrine of St Ursula.’ The Empress knew French courtiers asserted their Queen had the persuasive skills of a bishop and the guile of cardinals. She had no idea where St Ursula’s shrine was. Neither did Eleanor: she had just invented it. ‘The gold you spent buying her you’ll receive in heaven multiplied a thousand-fold,’ she’d added. She kissed the Empress tenderly.

When she told Xena how she’d freed her, tears of laughter ran down the girl’s cheeks. ‘Saint who?’ she’d squealed.

In the winter forest now, the Queen gave her a playfully fierce look. ‘Tell me what else about the Duke!’

The girl, aged almost sixteen, had a beautiful broad face, large brown eyes and skin that in the hotter months in Outremer turned the colour of dark honey. Her hair was a mass of black ringlets she kept beneath a tight veil. She knew both Latin and Greek to speak, read and write and had already learned French.

Xena hesitated. ‘You won’t be angry?’

‘I’ll have you whipped, you wicked child!’ They laughed.

Over the course of the journey home the Queen’s ladies had spread stories about Xena: she was a spy; she reported to the Turks. ‘She’s bewitched Her Highness.’ When these whispers reached Eleanor she gave her ladies a tongue-lashing that left them white-faced.

‘I asked one of the milking maids who lay with him,’ said Xena.

Eleanor flared her small, fine nostrils. The royal physician, also a Greek from Outremer, had prescribed these special female servants to keep the King’s humours in balance.

Xena continued, ‘She said he gave her such pleasure she bit his shoulders so hard the marks of her teeth will stay for a month.’

The Queen’s expression was both contemptuous and avid.

His Majesty’s Masturbators, as Eleanor called them, were another cause for argument between Louis and his wife. Louis had assured her, ‘I find no pleasure in what they do.’

‘How strange, sire, the physician does not prescribe a similarly unpleasant physic to keep me strong and healthy,’ she’d replied.

‘You are deliberately unreasonable, lady. You know men and women differ in their bodily needs.’

‘I know no such thing. I know you and the physician assert it.’

He had stalked away, muttering the ‘Ave Maria’ to calm himself.

But there had been no arguments about the maids or anything else in the past several weeks because the King and Queen were not speaking to one another. Since the Pope had forbidden divorce when Eleanor in person had petitioned him in Tusculum, they had not exchanged a word – not since that night when the Holy Father had tricked them into sleeping in the same bed.

Eleanor wrote to her sister, ‘The Bishop of Rome imagines that one night together for a man and woman can undo twelve years of ill-starred union.’

When they had departed Tusculum she had sent Xena to listen for gossip.

‘They say that under the Pope’s roof you refused to lie with your husband and you threw a slipper at him. And His Highness wept, saying France would never have an heir. Then you tore his silken sleeping robe with your teeth,’ Xena reported.

The Queen nodded.

‘They say your blood is too close to King Louis’s, therefore God has closed your womb to an heir.’

It was on the ground of consanguinity that Eleanor had requested divorce: one daughter in twelve years could not be considered a blessed union. If Louis were to die there was no heir to inherit France. Wolves from every quarter – from Burgundy, Germany, Flanders and Normandy; perhaps even from England – would tear it to pieces.

‘They’re wrong in one respect,’ Eleanor had replied. ‘I did lie with my husband that night. I made my body as stiff as a plank and glared at him.’ He became incompetent, she remembered vividly, and said France would never have an heir.

Now she asked, ‘Which of the masturbators lay with Normandy?’

Xena’s broad face dimpled at her cheeks. ‘I spoke to Alys, Your Highness, but …’

‘So more than one?’

Xena reddened. ‘All, Your Highness.’

How bold, Eleanor thought. Her grandmother had a favourite saying: ‘Fortune favours the bold.’ La Dangereuse, as this great lady was known to the world, was painted naked on her grandfather’s shield. ‘She’s won me more castles than a hundred knights!’ he liked to boast. In warm and fragrant Aquitaine, where Eleanor was born, and which she owned, people were not so stuffy, nor so in awe of Mother Church, as in the north.

Louis and about twenty cavalry rode up fast behind them. The Queen, Xena and the men from Aquitaine and Poitou pulled their horses off the roadway beneath the bare branches of the oak forest. The King went by at a canter. As he passed his wife, Louis gestured with a gloved hand for her to join him so they could arrive at their destination side by side. When her grey Arab drew alongside the King’s mighty black stallion, he whinnied softly. He

was bred in Outremer, a gift from the Emperor of Byzantium. His eyes radiated waves of gentle light towards the mare, tempting Eleanor to say, your stallion wants to seduce my mare, but that could lead to another argument, and there was not time for one. The monastery’s white stone walls were already in view.

‘You have your miniver cloak,’ she said.

‘What’s that rag you’re wearing?’ her husband replied.

‘I had to borrow something.’

Louis knew that already, and from whom she had borrowed it. His men had been watching the Duke of Normandy since he first arrived.

Emerging from the forest, the King and Queen saw lined up in front of the monastery an assembly of monks, black gowns flapping in the cold, all chanting ‘

Laudamus Deus!

’ Foremost among them, dressed in white and gold, an ermine cape about his stooped shoulders, stood Abbot Suger, Regent of France while Louis was abroad and the cleverest man in Europe. He alternately clasped his hands and flung them apart in welcome to his earthly ruler.

Four young monks swung incense burners in the wintry air. Perfumed smoke seeped through the brass fretwork in lazy, fragrant coils, its scent evoking for the Queen the glories of Constantinople – here, on this cold, grey plain outside a city she loathed.

‘Not like the day we left,’ she said to Louis as they ambled to a halt before their welcome party.

He turned to her to smile, grateful she was pretending they were on speaking terms. He wondered if, when they dismounted, she would flinch at his touch.

‘We have experienced many challenges,’ he replied.

Challenges, Eleanor thought. Catastrophes was the word for what had happened since that glorious summer day in 1147 when thousands upon thousands of knights, infantrymen and ordinary

pilgrims had gathered on the plain at Vézelay, red crosses on their white tunics, the nobles’ scarlet-caparisoned destriers snorting and prancing. Pennants fluttered on a warm breeze. The Queen’s retinue of noble ladies, gold-booted ‘Amazons’ as they called themselves, cantered around her; some, laughing, even revealed for a moment a naked breast. How thrilling an adventure it had seemed back then!

Now the blood and treasure were spent. The might and morale of the Army of the Cross were broken. Companions were dead of fevers; warhorses of thirst, of hunger, of heat. The pride of Christendom had blown away on the gritty wind of Outremer.

Eleanor thought: And here am I, the caged Queen, thanks to the Pope.

She glanced around and smiled to herself. The Cluny monks – Our Pious Sodomites, as she called them – had the miraculous power of being unable to see women. Even the Abbot, as he advanced towards her, appeared to be greeting some person who stood just behind her left shoulder. Weeks earlier he had heard of the bedchamber events in Tusculum. Every cathedral, every abbey, every monastery, every priory and church had men who reported to him. Earlier there had been stories of her disgraceful behaviour in Tripoli. But the King, still love-smitten, rushed to her rescue from shipwreck, her adultery and incest with an uncle in Tripoli forgotten.

‘Your Highness is even more glorious, if that be possible,’ the Regent said.

‘No satin is as smooth as your tongue, Father,’ she replied.

For a moment they looked straight at each other. He was the most intelligent diplomat and strategist alive. But observing his bent back and the shortness of his breath, Eleanor thought, not for much longer. Yet she needed him to live – for Abbot Suger, unlike the Pope, would weigh her marriage against Louis’s need for an heir. And such was the Abbot’s stature he could sway a college

of bishops. Once the bishops of France gave way, so would the Bishop of Rome. ‘Father,’ she said, ‘we fear for the health of your body. Please do not stand in the cold.’

Suger loathed the Queen. ‘Her one virtue,’ he would say to friends, ‘is her extraordinary beauty.’ More exquisite than an Egyptian cat, he thought. A collector of antiquities, Suger liked to run his hand along the curves of a gleaming onyx statue of Bastet, goddess of felines, but would sometimes pause and slap her face. ‘That’s for you! Harlot Pussy,’ he’d exclaim. It became a drollery among the brothers to call each other ‘Harlot Pussy’.

The Abbot had hoped that in the two and a half years she was away, the privations of the journey would have diminished the Queen’s loveliness: she had been shipwrecked, captured by pirates, exposed to strange customs and food … He was disappointed. Her Highness was as spirited and vital as before and, if anything, more beautiful, more confident, more sophisticated. And, impossibly, more imperious.

He noted that while the Queen looked better than ever, the King’s long, elegant face was etched with two deep lines that had not been there when he took the cross. They ran down his cheeks, from under his dark eyes to the crisp black beard that outlined his jaw. A deep wound of soul showed in every movement of Louis’s presence. Had he been allowed to enter holy orders as he had wished, he could even, Suger believed, have become a saint. ‘But such are God’s mysteries,’ he’d said the day the Crown Prince died after tripping over a hog, leaving no one from the House of Capet but a shy novice monk named Louis to take the throne of France.

The tall monarch and the short Regent walked side by side towards the monastery chapel. Trailing them, the Queen allowed herself to fall further behind, until she could signal Xena to her side.

‘I notice that among many others who did not take the cross, the Duke of Normandy is now with you,’ Suger remarked to the King.

‘I refused to receive him. He’s been harassing my servants for the past two weeks.’