The Zombie Combat Manual (29 page)

Read The Zombie Combat Manual Online

Authors: Roger Ma

3.

Repeat:

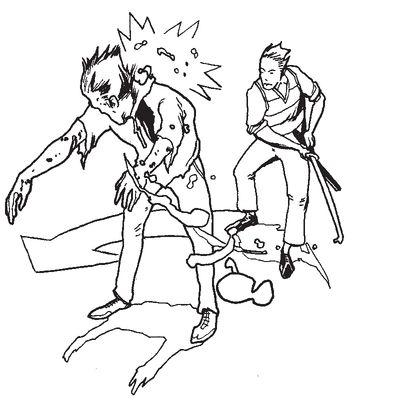

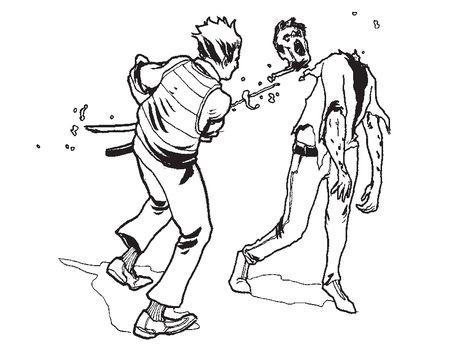

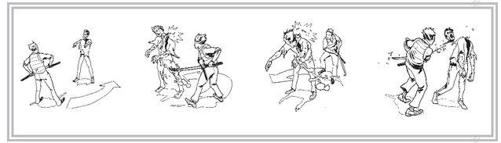

If your initial blow does not sever the head from its torso, do not panic. Circle approximately twenty-five degrees and strike your target a second time.

4.

Finish:

Repeat the preceding sequence of maneuvers until your undead opponent’s head is separated from its body.

Using this technique, most individuals are able to finish the engagement within two to three strikes. Should you find yourself unable to completely separate the head from the undead body, you have at least seriously compromised the ghoul’s ability to retaliate. Most important, you have kept yourself out of danger during your offensive attack. Remember, the severed head of a zombie requires a final, terminating blow to the brain.

COMBAT REPORT: LEE ZHEN

Shaolin Monk, Mount Song, Henan, China

I’m escorted up a craggy mountain trail by a brigade of warrior monks armed with Chinese long-pole weapons. Along the route, we hear the moans of several roaming zombies that have sensed our oncoming presence. Before I can even see the ghouls in the distance, the scouts in our party dash ahead and eliminate them before they are within a hundred yards of our position. Finally, we come upon a clearing that looks to be a large, well-tended vegetable garden. Monks and villagers work side by side to help cultivate the young, delicate shoots. It is here I am greeted by Lee Zhen, the Shaolin monk chosen to speak with me because of his command of English, which is remarkably good. Lee explains that he learned the language mostly by watching rebroadcasts of the American television show

Hunter

on CCTV. “Growing up, I wanted to be Fred Dryer,” Lee tells me as we sit down for tea while watching the work in the fields continue.

LZ

: Most people in the outside world, even within the main-land, had a misunderstanding of the Shaolin lifestyle. Many believed it to be an austere existence, one filled with fetching water, tending wheat fields, and hours of meditation, similar to what they saw on film and television. They thought it was, how you say, that phrase young people say meaning traditional, established?

ZCM:

Old school?

LZ

: Yes, that’s it. They did not realize that, just like the rest of China, the monastery had adapted with the changing times. We had cell phones, an e-commerce website, even a reality television show. Though many did not completely agree that this open adoption of modernism fit well with the historical spirit of Shaolin, no one argued that it brought additional funds to the temple, helping us prosper. It was not technology, however, that brought the living dead to our attention, but the will of the Henan people.

As you can imagine, the spread of information by public broadcast was somewhat restrictive in those days. Early outbreaks were attributed to dissidents, radical factions, Falun Dafa, and the like. It was at this time when we began receiving individuals at our gates, fearful of what they had been hearing from family and friends in other cities. It was a trickle at first: the lone farmer, a street vendor or two. This trickle slowly began to expand into a river. At this point, there were still limited actual sightings of any walking dead. But there was a feeling in the air; the people sensed it. Something terrible was soon to be upon them.

Finally, the dam burst. People by the dozens arrived daily, some already with their heads shaved, women and children included, wearing bedsheets tied into makeshift robes to show their devotion and commitment, anything to allow them to enter. We took them all in. At this point there was no covering up the situation—reports of infection were reported in Beijing and Shanghai and quickly spreading to the smaller outlying cities. Those with money—and there were many—fled the country to take refuge in the neighboring islands—Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines. But those who came to us for help, these were the ones without the funds, without any means of escape.

ZCM: Why not reach out to the government, or approach the local officials?

LZ:

You’re not very familiar with how things work here. There’s an old proverb that says

“Qiang da chu tou niao”

—“The bird that sticks out its head gets shot.” In this particular case, there was fear that the phrase would be taken literally. Besides, the government was too focused on major urban areas. They had no time or desire to help those left in the countryside. Soon, the temple’s sleeping quarters, training rooms, and courtyard were filled with crude tents, structures, and bedding from the hundreds who came to us for help. Many of them were

ganranzhe

,

15

weakened and frail. There was a concern among many of the monks that we would not be able to feed or care for everyone, especially those who were already sick. When confronted with this situation, the abbot simply replied, “Many of these people were forgotten by our country once already. Let us not have it happen to them again.”

Early on, before any of us realized what he was doing, the abbot was laying the foundation for his plan to manage the dire situation he knew would be coming our way. When villagers first began arriving at the temple, he quietly delivered messages to former students who were now employed in surrounding cities as bodyguards, security officers, and policemen. He also sent envoys with messages to the heads of kung fu schools within a two-hundred-mile radius of the temple. I am unsure of the specific content of the communication, but within days, many of the top students of various schools arrived. The abbot assembled all of the guests and the most skilled and senior of our monks together to articulate his plan.

ZCM: His plan?

LZ:

For half a fortnight, the abbot met long into the evening with various groups within the temple. At the time I was busy doing as I was told—feeding and tending to all the incoming refugees—so I was oblivious as to what exactly was happening. I did see many groups of monks coming and going from the temple at all hours of the night, many carrying tools and supplies. This went on for several weeks as we continued to receive countrymen by the wagonload.

One day when I awoke, nearly all of the villagers were gone, as were the guest students and roughly a quarter of the monks. It was after morning prayers that we were all finally told of what was to happen over the next several days. Roughly forty kilometers north of the temple lies a vast, open field where we often would assemble, meditate, and train. To the north of the field is the Yellow River. Mountains lie to the west, and fifty kilometers to the east, the city of Zhengzhou. The field is an idyllic place, an ideal location for the abbot’s intentions. We set out on foot and horseback just after breakfast, and arrived just before nightfall.

There was an odd smell in the air as we approached our destination. When I set eyes upon the field, I could hardly believe what I saw. A large bamboo platform had been erected, upon which sat two of the large meditation bells from our temple. Alongside the bells were racks upon racks of weapons from our armory. Each of the top instructors from the temple and neighboring schools was responsible for dividing us all into groups based on a single weapon class. We had teams wielding spades, axes, spears, broadswords, and a multitude of other weapons. It was then I noticed that most of the villagers were also present and separated into their own group, including many of the sickly ones. Given their lack of formal training, they were given their own choice of weapon, many selecting a simple cudgel or broadsword. Some preferred to wield a farming tool they brought with them. Everyone then sat down to dinner. When the meal was finished and the tables cleared, one of the bells was rung three times, and we all began to chant.

Our chanting continued unceasingly throughout the night, pausing only to punctuate the repetition with the deep gong of a meditation bell. The sounds echoed off the mountain ranges to the west and south. Then, just before daybreak, we began to hear them. The sounds were faint and low at first, barely audible above the sound of the wind gusting through the trees. Slowly, they began to grow louder in volume, as the air began to fill with a pungent odor. They were approaching from the east, just as the abbot had planned. The moans began to crescendo as they drew closer, blending with our chants into a single, horrific chorus. As hundreds of walking corpses began to wander onto the field, we rose from our

zazen

positions and prepared for battle.

The abbot summoned onto the field the first wave of monks equipped with polearms: spears, spades, and axes. Of all the hours we spent on the battlefield that day, this initial moment was the most dangerous. We heard many rumors about how to deal with this unknown enemy, none of which we knew whether or not to believe. Strike the head, strike the heart, remove the head from the body—all of these techniques needed to be tested during these critical first minutes. Several of the monks ran through their opponents with the seven-foot long

qiang

, only to have the creatures pull themselves down the length of the shafts to continue their attack.

We soon realized that head strikes and decapitation were the most effective. Those armed with

yuèyáchán

16

and broad axes were well prepared to sever heads from torsos. I witnessed Li Baobao, the monk most skilled among us all with polearms, decapitate seven bodies with a single whirl of his

guandao

,

17

as if he were channeling General Guan Yu himself! The monks needed to watch where they stepped, as the heads of the creatures continued to snap at them from the ground. The abbot then set loose other waves armed with shorter broadswords and bludgeons to follow alongside their long-range brethren. A rhythm began to develop between the ranks, where a polearmed monk would decapitate an attacker and then kick its head back to the short-range ranks to deal a final blow. It was quite a spectacle—rows of fighting monks, whirling, flailing, and striking. Our flowing, brightly colored robes presented a fiery contrast against the dulled landscape of thousands of walking dead.

The most impressive, however, were the

ganranzhe

. What they lacked in technique, they more than made up for in tenacity, especially the women. The abbot was cautious about sending them into the fray, but once engaged in battle, it is with no exaggeration that I say they fought with the fury of a thousand dragons. I believe it was because of the frustration they felt; not about having to leave their homes or their livelihood, or even about the living dead, but the faith they held that their country would help them in their time of need. That belief was tested twice in their lifetimes, and twice they were let down. They battled with a reckless abandon, with no concern for their safety or survival, and suffered greatly for it. Many I saw simply dove straight into a mass of creatures, flailing away until they were bitten, and then continuing to fight until completely overcome. Maybe that was their intention all along. Perhaps losing your life is less of a concern when you ultimately feel in control of your fate. Whatever the case, it was an epic battle, the most spectacular since Wengjiagang. Truly a valiant loss.