There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me (21 page)

Read There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me Online

Authors: Brooke Shields

Mom had insisted on a body double, and everybody was made aware of this fact. For the full-nudity scenes I would have a double, but for the seminude ones I would be somehow covered. I wore an extremely long wig, made from real hair, and it was long enough to cover my breasts. Even though my boobs were nonexistent, by the age of fifteen I had become self-conscious. The hair was long enough to cover them, but because of the wind, we had to secure the pieces to my skin with toupee tape. I called it tuppy tape, and every day when I took it off I’d stretch each strip as far as it would go. Toupee tape has a fun elasticity, and this activity became a tradition, bordering on an OCD tick for me. I’d have to stretch every strip or I got superstitious. I developed various mini-habits or neatening actions over the years and realize now that they were reactions to the frustrations and helplessness I felt toward Mom’s drinking.

After all the controversy surrounding

Pretty Baby

, I am sure that Mom was even more adamant about not having her daughter be nude. Mom loved reiterating this fact to the press. Even though the producers hated the press knowing I had a double, because they said it threatened the integrity of the film, Mom loved telling the world. She felt it proved to people that she had my best interests at heart. I always found it fascinating that a Hollywood producer’s idea of “protecting the integrity of a film” involved having a minor do her own nude scenes.

The company had trouble finding a suitable body double, so they ended up using thirty-year-old diver Valerie Taylor, who, with her husband, Ron, was responsible for filming the underwater shots. The couple had filmed all the water scenes for the movie

The

Day of the Dolphin

and could hold their breath calmly and for minutes at a time. The first time Valerie dove into the water wearing my long, natural

wig, the hair almost instantly matted up in a big mess. She came out of the water with a matted clump of hair worthy of Rastafarian status, and the shot had to be postponed. The wig, which came from England, was quite thick and cost thousands of dollars, and we had only one. Until we found another identical wig from England, we couldn’t film any of my scenes. They ended up having to get a synthetic wig for all the underwater shots. Mom loved highlighting how ignorant these people were not to know a natural-hair wig should not get soaked.

• • •

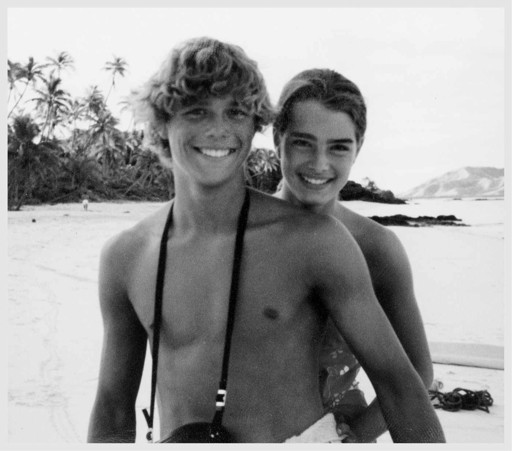

As filming continued, Chris and I went through a myriad of phases in our friendship. It began with my resenting the pressure I felt from the director to actually fall in love; then we actually had short crushes on each other; then he annoyed me and I’d not talk to him for a while except on film; then we’d forget all about the fight and act like friends again. Maybe it was love! We were more like siblings, and midway through the filming I remember Chris even moving into our bure.

Mom insinuated that she saw something she thought inappropriate, and thought it best if he stayed closer to us because nobody would mess with him if she were around.

Then I had to face the relationship between the director and

his

tanned, blond boy. I am not saying it was romantic, but the director was seemingly infatuated. The boy was, of course, Chris, and it made me crazy. I was less jealous than I was frustrated by how obviously enamored the director was with this Adonis. I felt constantly disregarded. No matter what I did, or what my mom said to me to make her feel better, I hated it. The attention remained on Chris. Chris would be doing a take and the director would marvel at how extraordinary his talent was.

He’d say, “You, Brooke, you’re the pro, but look at him; he’s a natural!”

I could feel my jaw clenching and the jealousy mounting. I’d

complain to my mom, saying he was a rookie and thought he knew everything and the director just played into this behavior. She’d tell me to forget it, adding that the director was probably in love with the kid. Mom often made quick judgments about things like this. She would often say somebody was probably jealous of me or that that director “had a thing for” that actor or actress. She wanted to be the one who saw everything and knew everything. She was confident that I would believe her wholeheartedly.

At one point the tension got so bad for me that I began disliking how Chris even held his hands. I became competitive with him. I wanted the director to approve of my work as much if not more than he approved of Chris’s. It was obvious that I was not going to succeed in this way. I found little ways to bug him and prove I was better than

he was. I’d follow him around on set and sing the lyrics to Supertramp’s “Take the Long Way Home.”

“So you think you’re a Romeo, playin’ a part in a picture show. . . .”

While filming water scenes, I tried to hold my breath longer underwater than he did and find more black coral than he did. I declared that I could drink more kava than he could and crack open a coconut faster. Truth be told, though, he could swim better and climb coconut trees faster than I could. I memorized my lines faster and I would correct him on his own if he messed up. I was basically being a brat. It never got ugly, thank God, and, over time, I got over needing constant approval from the director. Our angel cinematographer also noticed my needs and chose specific and necessary times to praise me.

Chris and I were never romantic, and because most of the intimate scenes in the film were between Chris and my body double, our relationship stayed platonic. They had to be nude together, but all I had to do was kiss him a few times.

I find it interesting that, once again, I was able to uphold a certain sense of innocence in what had been considered a provocative environment. My mom was with me on the island, but I was older than I was in

Pretty Baby

and I was rather self-assured. People really loved my mother on this movie. She was not viewed as a threat as if she had been by Polly Platt, and we were in a very contained space. She may have unsettled Randal by her mere attitude and proximity, but for the most part they all got along. There was a raw quality to this movie. We were all isolated together and in it for the long haul. It was safe and we were all connected and we were a team. Because people genuinely embraced her, I think she put up fewer defenses. There was something about the Aussies. They just knew how to meet people where they were, without judgment but with humor and a sense of adventure. Because they overlooked Mom’s deeper insecurities, they were a perfect group for both of us.

Plus, the Aussies knew how to party, so my mom fit right in. Even

on this location, Mom was able to find ways to keep busy. She’d often try to make calls to the mainland or help organize parties and themed events for the cast and crew.

God knows Mom loved a party and enjoyed being a part of any event where drinking was practically a prerequisite. A few times she took a seaplane to the mainland and delivered mail or brought back film, magazines, and even pizzas. Although the pizza delivery came to a quick halt when we turned over a slice only to find rat droppings embedded in the dough!

By this time Mom was drinking as if she had never stopped. It was like it had all been a dream. It was such a shame, but there was so much alcohol at base camp and around this crew that it was evidently just irresistible to her. Excessive consumption was not out of the norm for this lot, and it was very accepted. It’s amazing I never started then. I hated that Mom got drunk with the crew as much as she did, and I could not believe that after all the angst we went through for her treatment, it felt as if nothing had changed. Mom had

started back up again as easily as she had gotten into that car on the curb waiting to take her to the airport to go to a facility. I tried to just remove myself emotionally and, when I could, physically.

• • •

But by the end of August, I had hit a limit with island life. As much as I had submersed myself in that sandy oasis, I was ready to go home. Mom was equally ready to leave. She never went in the sun and I don’t remember her ever even going in the water. We were both ready for some of the tastes and comforts of home. We had become an incredibly tight-knit team, who experienced and suffered a great deal with one another, but I was homesick for New York. Shooting this movie had had an impact on all of us based purely on the long hours and sometimes intensely tough weather and living conditions, and we were all exhausted. We had lived through sicknesses, injuries, breakups, and even deaths of loved ones during filming. I still have scars lining my Achilles tendon from cuts that had ulcerated from swimming in water near a coral reef. It had been an intense, wonderful, and sometimes surreal experience, but it eventually got to all of us. Being away from home and from modern conveniences took its own toll, and we all needed an extended break from the island and from each other.

The first time I actually wrapped production, we were all packed and had taken off for and landed on the mainland of Suva. Mom and I went to a hotel to rest and wait the five hours necessary before catching our flight back to the States. After about an hour, we were contacted at the hotel and informed that some of the film had been damaged, and I was needed for an additional two weeks of filming. My heart sank. I cried when I realized I had to wait two more weeks before returning home. Cutting my hair all off would have had no impact on this movie because I wore a wig, so I felt even more helpless.

I’ll never forget the real last day, when we were finally able to leave.

We were doing one last scene on the beach. Before it was over, the seaplane arrived. It coasted to the dock and waited. I remember looking at it and thinking that no matter what happens, the moment I start walking on that dock, I am not stopping. I told Mom I didn’t care if the film blew up; I was going home. She concurred.

There was a part of me that also did not ever want to leave Nanuya Levu. Not because it had been paradise, but because on this island it felt easier to keep my mother alive. Losing Mom was a constant fear of mine, but these four months the panic surrounding her possible death had waned slightly.

We took off for the mainland, and as I saw our island getting smaller and smaller, my mind wandered to the impending future of my mom’s drinking. Dread began creeping back into my stomach. Without the containment of the island and the protection of the crew, I would be alone with her alcoholism yet again. Mom and I had been in somewhat of an unrealistic bubble in the middle of nowhere, but once back in New York City she would be on the loose again. I would no longer easily know her whereabouts. The island and the crew and the tough schedule had provided me with a huge safety net, but now that this protective zone was receding, my heart began to grow heavy. Before long, I would be resuming my hypervigilance. Intervention and rehab had been a mere apparition. I was going back to square one in the battle to survive my mother’s disease.

We got to the mainland and would have to wait for the 2:00

A.M.

connecting flight. We would have dinner at the hotel plus a few hours of rest. Then we’d fly back to the United States and it would begin to feel like it had all been a dream.

• • •

The Blue Lagoon

had a huge premiere a year later, in June 1980, at the famous Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles. It was my first time at this theatre and it was quite exciting. The building seemed immense and

I was blinded with light and by the sight of Chris’s and my face covering the entire side of the building. There was excitement and anticipation in the air. My stepsister, Diana, came out to be with me for the press junket and kept me laughing the entire time. This was something that Mom had negotiated into my contract. This was unprecedented—getting the studio to pay for a companion for me during a junket. But it kept me contented, so they couldn’t fight it. It was good for everyone.

Mom even had a friend flown in to the island to visit. I’m not sure if the studio paid for the ticket but she always negotiated multiple tickets so I could have a friend or Diana come to visit. Mom felt it important for me not to feel lonely or stressed by the press, who as we knew could be unkind. I needed a partner in crime. This was an unheard-of request, but I had no agents or publicists for the studio to pay for, so Mom could justify the expense. According to her, they were getting off easy. My mother and Diana were my entire entourage. Diana understood Mom’s battle with booze and she also loved and laughed with my mom. She was on our side.