Things Invisible to See (17 page)

Read Things Invisible to See Online

Authors: Nancy Willard

I’m supposed to be keeping up with my schoolwork. The math is beyond me; it’s also beyond Nell and Mother. So much for math. I read a little French but not very energetically. And novels, though all we have in the house are Poe and Dickens. I haven’t been to the library in ever so long.

I do a lot of drawing. I did a good portrait of Nell, but she didn’t like the little lines around her mouth and the shadows under her eyes, and last night she sneaked into my room and erased them.

Mr. Knochen hasn’t been back, but I think about him a lot. Ben, be careful. I will ask my Ancestress to help you when I see her again, but when will I see her? Maybe she won’t come anymore. Mother told me she lost most of her power over the invisible after she fell in love with Papa. You have to give up one for the other, she said. Most people don’t have room for both.

I love you. So perhaps the Ancestress won’t come, ever again.

On the other hand, she might. She comes when she’s needed. But I can’t ask her. She comes in her own way.

Love,

Clare

Sol Lieberman to Ben Harkissian

February 15, 1942

Dear Ben,

No doubt Clare has already written you that I’m teaching her baseball. I think if she gets to know the game, maybe she’ll move a little faster down the road to a cure.

I wish the news from home were all good, but it’s not. Durkee was killed in action in the Philippines. I feel just awful about it. And now that everybody on our old team has enlisted but me, I have to keep reminding myself that when the war is over, people are still going to need doctors.

Tell Clare that you’re the one responsible for putting her in a wheelchair. If you get killed, God forbid, and somebody else tells her, how do you think she’ll feel? It’s more important to ask her forgiveness than God’s. God will always be there, He can wait. But you and me and Clare and the rest of us—who knows when we’ll be taken?

Take care of yourself—

Your old pal,

Sol

Ben Harkissian to Clare Bishop

Fort Hood, Texas

February 20, 1942

Dear Clare,

This is the hardest letter I’ll ever have to write. And I hope I don’t lose you for writing it. I couldn’t bear that right now. The chance of seeing you again is what keeps me going.

I’m the one that hit you with the ball. A bunch of us were fooling around on the golf course, across from Island Park. George Clackett pitched me a ball and I hit it. I never saw where it went. But I read about you in the paper and I wanted to tell you but I kept putting it off. If I get killed, I want you to know the truth, and I want you to know it from me.

Write. Write soon. Or call. It’s awfully hard for me to get a call through to the outside. Every night there are a hundred men in line for the telephone. We’ll be going overseas soon. They don’t tell you where you’re going till you get there. I’ve learned to kill in a hundred different ways. I’ve learned how we kill and how the enemy kills. Steel darts, butterfly bombs, personnel mines, castrators (you step on one, it blows your groin out). Oh, God, I wish I could ask forgiveness for everything I’m going to have to do. I don’t want to kill. I wish I could bandage the wounded or set the broken wings of birds.

Love,

Ben

P.S. You keep working out with Sol. That tingling is a good sign.

Clare Bishop to Ben Harkissian

Ann Arbor, Michigan

February 28, 1942

Dear Ben,

When I read your last letter, I nearly fell out of my chair. I won’t tell you all the thoughts that raced through my head. What matters is this. If you hadn’t hit that ball, we’d never have met. And I think my real life started from that moment. Oh, I ate and slept and walked around, but I was asleep. When I think about my life B.B. (before Ben), the days are all the same color, they run into each other like water. There’s so much that slipped over me, so much I didn’t notice or remember.

Meeting you the way I did was an awful way to wake up. But I’d rather be awake than asleep.

We hear a lot about keeping awake now. Keep awake! The enemy never sleeps! In Meeting one of the elders made my heart stop when he stood up and spoke a passage from George Fox’s journal: “Now was I come up in spirit through the flaming sword, into the paradise of God. All things were new, and all the creation gave unto me another smell than before, beyond what words can utter.” I believe the flaming sword is double-edged—it wakes you and it wounds you, and I thought of you and me, and if life is being taken from us, I want to be awake when it happens. I want to know what I’ve lost.

If you want to save things, you should be here. We’re saving scrap. Paper, old tires, iron. I’d like to scrap this chair. I wish somebody would come up to me and say, “Take up your chair and walk.” Are there still people around who can say that and mean it?

My baseball lessons go on. Sol is a wonderful teacher. And I love you.

Clare

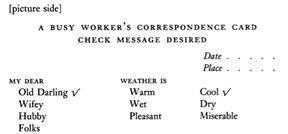

Davy McGuinley to Hal Bishop

[postcard]

A Greedy Eye

A

FTER BEN LEFT, WILLIE

and his mother began every morning with a discussion of Marsha.

“It’s just as well he’s rid of her,” said Willie.

“Just as well,” agreed Wanda. “Such a terrible girl.”

Willie said, “Terrible,” and thought of Marsha’s tearstricken face and her white rabbit coat and her money and remembered how her head felt against his shoulder and the sly look she gave him, as if she were reading the future in his face.

One morning Willie observed that his mother was growing tired of this subject, and he feared that unless he mentioned Marsha first, they might not discuss her at all, and he would lose the pleasure of parading Marsha’s faults, a pleasure oddly akin to prayer, for it seemed to bring him into the very presence of her to whom all this talk and energy were directed. A new morsel of information would sustain his appetite for weeks.

“Her stepfather is Dr. Deller,” said Wanda. “Did you know that? Don’t forget to drink your orange juice.”

Willie drank it very fast.

“His specialty is eyes. He has a big wooden eye in his examining room with Arabic writing on it.”

“Who told you that?”

“Mr. Nesbitt. Dr. Deller operated on him for cataracts.”

“What does the writing mean?”

“I don’t know,” answered Wanda.

“Maybe Mr. Nesbitt could find out.”

“What do you want to know for?”

“It’s nice to know things like that,” Willie answered.

A week later she told him what it meant: Don’t have a greedy eye.

“He overcharges,” she added.

In his mind Willie kept a compartment marked “Marsha, Priority,” in which he filed the most casual remarks and tried to assemble them into a larger picture of their subject, while he listened for new tidbits of information floating in the stream of his mother’s talk. One evening over supper his mother said, “Dr. Deller came in today.”

“What for?” asked Willie.

“He brought a bunch of Marsha’s dresses to be cleaned.” Willie felt himself go weak. Wanda went on relentlessly. “He used to go down the street to Spotless and Cheap, but they lost a pair of his trousers, so he’s switching to us. I never saw a girl with so many clothes. He told me she never gets rid of a single outfit.”

When Willie stopped by Goldberg’s Cleaners & Tailors at noon and offered to take her to lunch, his mother was surprised and pleased. “But I can’t leave the counter till Joe comes back from his lunch break. We’re awfully busy at noon.”

“Is there anything I can do to make myself useful?” asked Willie.

“You can keep out of the way,” she said. “I have more work than I can handle.”

She brushed him aside and took an armload of shirts from a man who was drumming his fingers on the counter.

“No starch, Mr. Siegl, right? And you want ’em on hangers.”

Mr. Siegl nodded. “My wife’s pink dress is in that pile,” he warned her. “She wants you should get the sweat out of the armpits.”

Wanda filled out another slip. At the bottom she scrawled, “Sweat Under Pits.”

“When will it be ready?” asked Mr. Siegl.

“Saturday, unless you want to put a rush on it.”

Willie lifted the gate in the counter and closed it behind him and slipped into that vast, noisy nation of steam presses, whirling drums, women old before their time pushing bins of dirty clothes, and garments rustling on racks that stretched into infinity. He watched a girl unroll giant bags from a spool over her head and ease them down over the finished dresses that scooted down the rack toward her like obedient children waiting to be checked. A call from the far side of the room sent her running.

Mr. Siegl was gone, but another man, with an armload of tablecloths, had taken his place.

“Mother, let me bag some of the finished dresses,” said Willie. “You can trust me.”

He knew from the way she glanced at him over her shoulder as she wrote out a slip for the tablecloths that he was in her way.

“I could do Dr. Deller’s suits. Or Marsha’s dresses, if they’re ready.”

She shrugged, and he thought she gave him an odd look, but she said nothing, only pointed to the rack behind her.

“Marsha’s dresses are at the far end. They’re all marked.”

The white rabbit coat told him he’d found what he wanted. He leafed through the clothes on the rack as if turning the pages of a powerful book. There was only one copy of this book in existence and only one opportunity to turn its pages. A white satin blouse. A gold lamé skirt so narrowly cut that Willie, accustomed to the sight of Wanda’s stocky figure, could hardly believe that any flesh-and-blood woman could fit into it. Ah, here was an old friend: the strapless evening gown, tagged with Marsha’s name and the date her mother, or Dr. Deller, or perhaps Marsha herself, would call for it. He took out his pocket notebook and tore out the page on which he had copied with great care:

When as in silks my Marsha goes

Then, then (me thinks) how sweetly flows

That liquefaction of her clothes.

He added a single line of his own: “You looked wonderful in this dress.” With trembling hands he pinned it into the bodice and noticed that it was lined with stays and a stiff, heavily padded bra. He drew a white bag over the dress and pushed it along the rack.

Only after he had bagged thirty-two dresses, all Marsha’s, did he remember lunch.

He spent the next week seesawing between repentance and anticipation, both of which peaked when Wanda came home from work. In vain he waited for a cryptic confession of love on small perfumed paper, or a note saying he might call. Had he forgotten to sign his message? Had it fallen off? Had Marsha put the dress away for the duration without inspecting it? Or had she found the note ridiculous, even offensive? Angry, first at her and then at himself, he thumbed through his

Encyclopedia of Etiquette: What to Do, What to Say, What to Write, What to Wear

for a letter to copy, a rule to follow. He found a useful heading, “Accidents,” but the only disasters acknowledged were accidents at the dinner table. Nevertheless, he scanned the section for useful phrases:

Mishaps will overtake the best-regulated diner, who, however, when anything flies from the plate or the lap to the floor, should allow the servant to pick it up.

If an ill-starred individual [Willie turned the page hopefully] overturns a full wine or water glass at a dinner table, profuse apologies are out of place. To give the hostess an appealing glance and say, “Pray forgive me, I am very awkward,” or, “I must apologize for my stupidity, this is quite unforgiveable, I fear,” is enough.

Willie read the last paragraph over twice and wrote, on stationery bearing the gold embossed crest of the Episcopal church:

My dear Miss Deller,

Forgive me, I am very awkward, I must apologize for my stupidity. My pinning that poem to your dress was unforgiveable.

Believe me sincerely yours,

Willie Harkissian

Two days passed before her answer came, on a sheet that carried her name in huge block letters at the top and below it, a brief message: “Don’t worry about it.”