Thirty Rooms To Hide In (8 page)

Read Thirty Rooms To Hide In Online

Authors: Luke Sullivan

Tags: #recovery, #alcoholism, #Rochester Minnesota, #50s, #‘60s, #the fifties, #the sixties, #rock&roll, #rock and roll, #Minnesota rock & roll, #Minnesota rock&roll, #garage bands, #45rpms, #AA, #Alcoholics Anonymous, #family history, #doctors, #religion, #addicted doctors, #drinking problem, #Hartford Institute, #family histories, #home movies, #recovery, #Memoir, #Minnesota history, #insanity, #Thirtyroomstohidein.com, #30roomstohidein.com, #Mayo Clinic, #Rochester MN

Jesus.

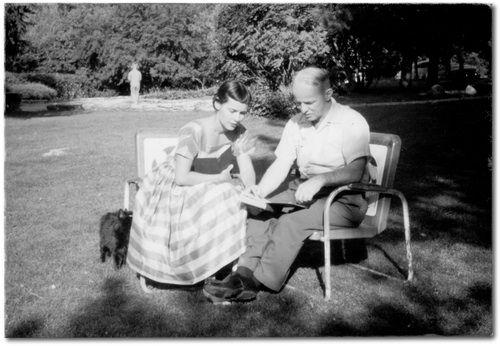

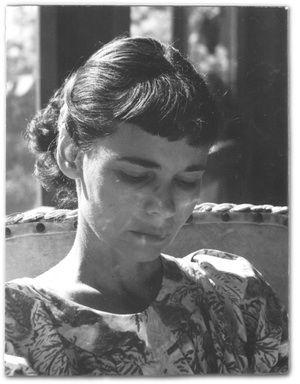

Myra and the short haircut she hated. Circa 1960.

“You-know-who came home in a foul mood tonight.”

That sentence, in one of Mom’s 1958 letters, was the lump in the breast, the iceberg off starboard bow.

In 1958, the term “chemical dependency” didn’t exist. “Boozer” might have. “Party guy,” definitely. But alcoholic? Chemically dependent? Forget about it. Alkies flew under the radar. You could smack the wife, wreck the car, take a shit in the neighbor’s bird bath, and as long as you showed up for work on time all anybody did was roll his eyes.

“Having a delicious highball or two is a great way to unwind,” read the magazines. Even today when drinkers get shit-faced and do horrible things, people give them yards and yards of slack. But in the ‘50s and ‘60s, America was an especially confused culture on the subject of drunkenness. Dean Martin slurred his way to prime time and all the Dads in suburbia laughed while pouring another one. Drunk jokes are still common; and they’re

funny

.

So this drunk staggers into the church, okay? He sits down in the confession booth but says nothin’. The bewildered priest coughs to attract his attention, but the man says nothin’. The priest knocks on the wall a couple of times in a final attempt to get the man to confess. The drunk replies, “No use knockin’, buddy. There’s no paper in this one either.”

Couple the cultural confusion about alcohol with a woman’s place in 1950’s America and you have something like checkmate. My mother didn’t see checkmate coming and even if she had she couldn’t have done a thing about it. Mention to Roger his drinking was starting to scare her? It wasn’t in the realm of possibility.

As I sort through Mom’s letters, I wonder exactly when Roger became an alcoholic. Was it the drink Mom mentions in a letter on January 30th, 1958: to “unwind” after his boss cut the time he needed to prepare a presentation on pediatrics?

Perhaps it was the one he poured on May 30th, 1956: the night she wrote how he came home angry at a medical technician in the O.R. I imagine Roger putting the stopper in the neck of the bottle, then maybe popping it off again to pour that extra half-inch over the ice, talking over his shoulder about how the idiot technician didn’t move fast enough and this is an

operating

room, for crying out loud.

Maybe it was his very first drink.

The one on that marvelous night 12 years ago. You remember, in medical school, back when the war was over and Irene was no longer just down the hallway listening for heresies, and it was just you and Mack and Kupe and Tunk, you all had your booth at the Town Taverne and – damn – the wine really warms your chest from the inside out, doesn’t it though? And the words, they just come so fast and easy and everybody seems so happy and Jesus how you laughed and you all fit in so well and the cigarettes tasted better and even though it was late you didn’t wanna go you didn’t wanna stop you just wanted more of that same good feeling and more and more of it.

Going through the photos and letters, I begin to realize that trying to carbon-date the exact hour of the monster’s appearance is futile. It wasn’t a moment anyway, but the slow dawn of a long era. Alcoholism crept into the Millstone so quietly no one noticed.

In fact, as I re-read Mom’s early letters I begin to see where she was writing about Roger’s alcoholism without realizing it.

Mom, January 30, 1958

I seldom see Roger lose his patience with Clinic policy or pronouncements but he came home last evening in a monumental rage. His time to prepare for the presentation of his paper had been worse than halved! He goes to Chicago early to set up an exhibit he has planned but now has to be back Tuesday. His exhibit and paper prove a theory of his that the blood supply to the talus is not through a single artery but several. Says Roger, “It simply stands to reason. God wouldn’t have made it that way!!”

My mother says she thinks it was 1958 when bottles gradually began to appear on that shelf in the kitchen. Gradual also was the appearance, in my mother’s letters, of my dad’s souring temperament. She mentions a bit of snappishness here, an angry moment there. Reading the letters again, the pattern seems clear but at the time it wasn’t. The first attacks were mostly put-downs, jibes at Mom’s character calibrated to make her feel bad about herself. If Mom bought a new Erroll Garner album of jazz piano it was “Why did you waste money on

this

?” Everything she did that wasn’t housekeeping was cause for eye rolling, derision or contempt. The worst thing was that, for a long time, Myra believed him. In a letter to her father, she wrote, “Call me a crazy fool if you like – I am! What poor man other than Roger has to suffer a wife who takes horseback riding lessons and string bass lessons, and builds model ships! Poor Roger.”

Poor Roger also expressed contempt for Myra’s love of reading, a subject he would return to again and again: “Why are you wasting money on books?”

Looking back today, Mom says, “Even my Greek studies were seen as further proof of my inadequacies. And my beautiful instrument, the cello? Given up to avoid more recriminations from you-know-who. He was unappeasable. In college days when I wore my homemade Florida dresses and big white pearly button earrings, he was embarrassed that his roommates called me ‘El Gitano’ – the Gypsy. But then by 1957, I was disapproved of for wearing my hair in a

conservative

bun.”

When the bun wouldn’t do, she acquiesced to a shorter hairstyle in front, confessing in a letter, “I hate it – but my husband likes it – so what else can I do?”

I go back through the family photographs and find the September ’57 shot of Mom in the shorter hairstyle. For the first time, I discern she was angry when the picture was taken. When I show her the picture, she says yes she remembers trying to ignore Dad and his camera, looking down at her book, embarrassed at having to pose like a shorn prisoner of war. When I mention I’ve had trouble figuring out exactly when dad’s drinking went nuclear, she says, “I’m not sure, but one incident does come to mind.”

She was pregnant with Collin when she had her first look into the lupine eyes of Roger’s true rage – which would make it 1957. In the summer of that year my parents hosted a Mayo Clinic party at the Millstone. The festivities were winding down to a very late end and at 2am only a single guest remained, drinking and talking loudly with Roger. She doesn’t remember his name, only that he was the kind of saloon fixture who’d quickly show up on my father’s radar

(“I hail from Texas. Where the ‘hail’ you from? HA-HA-HAAAA!”)

: the too-hard laugh, the high-and-tight haircut, the florid skin of the veteran drinker. With five of his children sleeping upstairs and his pregnant wife standing right there to hear it, Roger began telling this sodden stranger what a horrible wife Myra was. She stood there puzzled, then insulted, then sick at hearing lies so cheerfully shared with this bar-stool tumor: “She’s frigid, Bob. Won’t have sex. Don’t make the mistake I did, Bob. Don’t marry a woman like this.”

It was the eyes, she said, the eyes that were the worst. There was nobody back there anymore; not a person anyway but something else, a sort of predatory cunning that peered out and looked for things it disagreed with, looked for things to FUCK WITH.

One night she was just about to lead her four youngest boys upstairs for the customary bedtime story. Dad walked out of his study where he’d been drinking since 5:00. He stood at the foot of the stairs and calmly put his leg out across the staircase, blocking her ascent.

“You are not going to turn those boys into sissies by reading them to sleep,” he told her. “Let them go to sleep on their own.”

No further explanation. No discussion. Just the eyes.

It wouldn’t be until May of 1964 when Myra began writing openly to her parents about how life really was at the Millstone. For now, instead of saying Roger came home drunk and yelled at the kids, she wrote “the kids caught you-know-what from their father.” She wasn’t ready to open the furnace door and let them see into the Millstone, to witness their daughter burning. So she said nothing.

But Myra’s parents picked up on some of the trouble at the Millstone anyway. Myra and RJL had planned a trip in 1958. Mom was to come visit her parents in Florida.

It was a trip talked about in their letters, planned there, and warmly anticipated. Then Grandpa RJL received a Western Union telegram from Minnesota; a dozen apologetic words glued in a strip on yellow paper: “FORGIVE ME. HAVE BEEN TOO HASTY. SOMETHING MAY YET WORK OUT. – LOVE MYRA.”

In 1959, she guardedly mentioned to Roger renewed plans for another trip to Florida. Surprisingly, he agreed but then began to sulk, sitting alone in his study. Later, as the drink took effect, his eyes would get the look and he’d rage.

“How in God’s name do you think we have the money for this? For you to run off and see Mommy and Daddy? Huh? You make me buy this goddamned house and fill it with kids just so you can go waltzing off?? Grow up, will you? Just GROW UP!”

Rage is different than anger.

Rage is the inferno firemen don’t even try to put out. There’s no talking to rage. Anger is explosive; rage is nuclear. Rage is the end of hope – Armageddon. In this new nuclear landscape Myra realized fighting back meant unleashing her own anger which, in the parlance of the times, was “mutually assured destruction.” All she could do was to keep silent. Anything she said in her defense would only escalate the attack. She just had to wait it out.

By morning the rage would be gone but Roger’s silence and the way he slammed the door on the way to work made it clear any trip to Florida would cost more than money. At the Clinic he was still the charming, brilliant doctor and giver of care to all. Back at home his wife was sending yet another telegram with another excuse just vague enough to finally prompt Professor Longstreet to call his daughter “to see if everything was all right up there.”

Being a somewhat worse liar on the phone than in a telegram, Mom would back-pedal a bit, and say, “Roger thinks with money as tight as it is perhaps it’s best to wait.” (No mention of the nuclear rage, the fallout.) “But don’t worry, we will work something out.”

No matter how Myra tried to spin it, RJL suspected things at the Millstone were not entirely right. Still, as thin as her excuses were, at least she kept the cops from looking in the trunk.

Mom’s final letter from the ‘50s, New Year’s Eve, 1959

And so another year has passed, and on the whole it has been a good one. 1959, the last of another decade ends jubilantly! My only cause for remorse is my weakness in exposing you to unnecessary alarm and helpless concern [regarding the cancelled trip]. For which forgive me. The 1940s were a fateful ten years, bringing college days, tuberculosis, marriage, and two children before their close. The 1950s brought a mighty economic improvement, our beautiful home, and four more sons. Life has been lavishly kind to me these twenty years. God (and the politicians of this world) willing, “the best is yet to be.”