This Great Struggle (39 page)

Read This Great Struggle Online

Authors: Steven Woodworth

Meanwhile, Burnside had had a run-in with another prominent Copperhead. Wilbur F. Storey, the virulently Copperhead editor of the

Chicago Times

, enraged Burnside by his paper’s unrelenting hostility to the Lincoln administration and the Union war effort. On June 1 Burnside issued an order stating, “On account of the repeated expression of disloyal and incendiary sentiments, the publication of the newspaper known as the

Chicago Times

is hereby suppressed.” An immediate furor arose, and Lincoln revoked Burnside’s order.

MANEUVERING AGAINST THE ENEMY, LATE SUMMER, 1863

Meanwhile, back on the fighting fronts, the late summer of 1863 saw lulls in both regions that had been the scenes of heavy action during the late spring and early summer. In the Mississippi Valley, Grant’s army consolidated the vast gains of the Vicksburg Campaign, and the authorities in Washington diverted a significant portion of Grant’s strength, the Thirteen Corps, to Bank’s Department of the Gulf.

As Grant later noted ruefully, the troops were sent where they could do the least good. He would have liked to have resumed the offensive with a drive against Mobile, but Lincoln and his advisers in Washington were eager to establish a Union presence in Texas, where the French emperor Napoleon III was in process of setting up a subservient regime under the rule of puppet emperor Maximilian, a clear violation of the Monroe Doctrine. In theory, Napoleon would be impressed by the arrival of Union troops in the vicinity of the border and would abandon his Mexican adventure. As it turned out, all such efforts, like any other plans that placed troops under the command of the dismal Banks, were doomed to failure. The quickest way to get the French out of Mexico would be for the United States to triumph over the rebellion and then turn its undistracted attention to Maximilian and his French master.

The other sector that had seen heavy fighting during the early summer was the eastern theater, where Lee’s Pennsylvania gambit had failed at Gettysburg. Though somewhat reduced in numbers, Lee’s army was in a much better state of supply than it had been at the beginning of the summer thanks to the abundant booty it had plundered from the Pennsylvania countryside during the Gettysburg Campaign. On the other side of the lines, Meade was cautious as ever. Lee was first to take the offensive again, moving deftly around Meade’s flank and marching north to threaten Washington as well as Meade’s supply line. Cautiously but with equal deftness, Meade fell back, denying Lee the advantage he had sought. Hoping to catch and damage Meade’s army as it withdrew, A. P. Hill, commanding Lee’s Third Corps, struck incautiously at a Union column near Bristoe Station, Virginia. A brief reconnaissance would have revealed far more Federals present than Hill had imagined and in a very strong position. Hill’s corps suffered a bloody repulse, and Lee, seeing that the campaign would accomplish nothing, ordered his troops back to their camps south of the Rapidan and Rappahannock. Thus, for a fifth time since the eastern armies had established themselves on opposite sides of those rivers, an offensive foray by one side or the other had ended in a failure that left the strategic situation in Virginia unaltered.

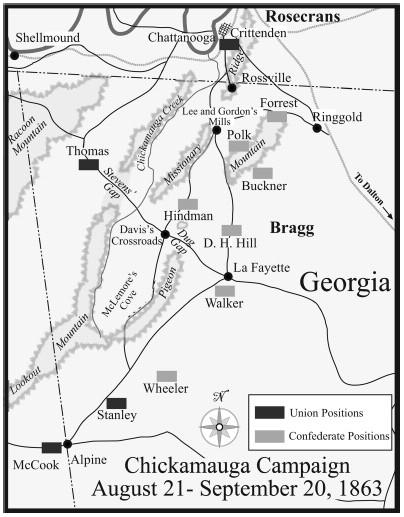

On the central fighting front, in Tennessee, where William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland faced Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, the situation was much different. Early summer there had brought no heavy fighting but rather the almost bloodless maneuvering of the Tullahoma Campaign, by which Rosecrans had expelled Bragg from Middle Tennessee. Handicapped by the near-mutinous state of his top generals, Bragg had fallen back all the way to Chattanooga, almost on the border with Georgia, while Rosecrans had halted his advance near Winchester, on the opposite (northwestern) side of the Cumberland Plateau.

Lincoln, Stanton, and Halleck had been almost at the end of their patience with Rosecrans over his six-month delay between the Battle of Stones River and the Tullahoma Campaign. When that campaign halted without a major battle and with Bragg’s army still intact, their annoyance began to grow once again. Rosecrans insisted on halting his army until its state of supply and equipment was once again as perfect as he could make it. Six weeks passed, and it was August 16 before the Army of the Cumberland once again marched out of its camps to follow up its previous advantage against Bragg.

While Rosecrans had used the six-week midsummer lull to refit his army, the Rebels too had been busy. For months a coterie of influential Confederates had been urging that the Confederacy’s best strategy was to concentrate its strength in the center for a decisive, war-changing blow that would crush Rosecrans and begin the unraveling of the Union’s effort to restore the southern states to their allegiance. Rosecrans’s success in the Tullahoma Campaign, with its inherent threat to Chattanooga, finally galvanized the government in Richmond into acting on that plan. Davis overruled Lee’s objections and ordered James Longstreet with two divisions of his First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia to reinforce Bragg for a counterstroke against Rosecrans.

By the time Longstreet’s detachment got under way, Union troops under Burnside, now leading a one-corps Army of the Ohio, had advanced from Kentucky and captured Knoxville, Tennessee, cutting the direct rail connection between Virginia and Chattanooga. Longstreet’s troops therefore had to ride the trains all the way down the East Coast and then back north through Atlanta to join Bragg. This delayed their arrival until the second half of September, but their presence, along with that of various reinforcements Davis ordered to Bragg from other corners of the Confederacy, would raise the Army of Tennessee to nearly seventy thousand men, its greatest ever numerical strength and enough to claim a moderate advantage over Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland.

The reinforcements were not with Bragg when on August 16 Rosecrans launched his new campaign. As usual, the Army of the Cumberland’s commander had prepared meticulously, and his plan demonstrated how powerful a factor it was to be allowed to choose the time and place of action. Although his army had to cross several formidable barriers, Rosecrans’s possession of the initiative turned each of them to his advantage. The first barrier was the Cumberland Plateau, and immediately behind it lay the broad Tennessee River. For Bragg the problem was that the plateau was a barrier sufficient to prevent cavalry reconnaissance—especially reconnaissance directed by Bragg’s rather mediocre cavalry commanders—but nevertheless contained more gaps than his army could possibly hold in strength. As Bragg put it, “A mountain is like the wall of a house full of rat-holes. The rat lies hidden at his hole, ready to pop out when no one is watching.”

Complicating the problem for Bragg was Burnside’s possession of Knoxville and potential threat to move down the Tennessee Valley and link up with Rosecrans, a threat so severe that Bragg simply could not afford to permit it. He had to play Rosecrans strong to the northeast of Chattanooga even at the expense of leaving a weak side to the southwest of the town, where a Federal passage of the mountains and river would be less immediately disastrous. In the end, that was exactly where Rosecrans made his move, feinting elaborately upstream of Chattanooga, then pushing his army quickly across mountains and river below (southwest of) the town. By the time Bragg learned of Rosecrans’s advance, the Army of the Cumberland was already across the Tennessee River and pressing east toward the final barrier, the long ridge known as Lookout Mountain. Towering as much as 1,400 feet above the surrounding terrain, Lookout extended several score miles southwest from Chattanooga, where it loomed over the town, across the northwestern corner of Georgia and well into Alabama. Surmounted by a rocky escarpment known as the palisades, Lookout could be crossed only by tortuous mountain roads and then only where gaps in the palisades allowed passage.

Once again the initiative and the corresponding advantage belonged to Rosecrans. Moving his army in three widely separated columns to take advantage of as many far-flung gaps, the Union commander made it impossible for Bragg to discern the exact points of advance until it was too late to counter. With that, Rosecrans had successfully turned Bragg’s position in Chattanooga, threatening his supply line back toward Atlanta and putting him in immanent danger of being trapped against the Tennessee River just as Pemberton had allowed Grant to trap him against the Mississippi at Vicksburg four months before. Bragg was too canny to let that happen, so he took the only other option and put his army in retreat southward out of Chattanooga.

While one of his three corps moved in and occupied the key rail junction town, Rosecrans, traveling with his center corps twenty-four miles to the south, stood atop Lookout Mountain and observed the long cloud of rising dust to the south of Chattanooga that could mean only that Bragg was in retreat. Rosecrans’s reaction was to pursue, and he ordered all three of his corps—the Twenty-First at Chattanooga, the Fourteenth with him twenty-four miles to the south, and the Twentieth another eighteen miles farther south—to press eastward as rapidly as possible and tear into the flanks of the fleeing Rebel column.

The problem with all this was that Bragg’s army was not fleeing. The wily Confederate had shifted south twenty-five miles from Chattanooga to the town of La Fayette, Georgia, in order to escape Rosecrans’s trap, but he and his army were as yet far from defeated. On the contrary, the Rebels were at bay, looking for an opportunity to strike at their tormentors—and the long-awaited reinforcements were beginning to arrive. By pressing his campaign beyond Lookout Mountain, Rosecrans was following the pattern he had set after the Battle of Corinth eleven months before, trying to exploit momentum he did not have. This time, however, Grant was not on hand to stop him.

As Rosecrans pressed forward, Bragg soon found the opportunity he sought. On the evening of September 9, scouts brought him word that a Union division had crossed Lookout Mountain via Stevens Gap, twenty-four miles south of Chattanooga, and descended the west slope into a side valley known as McLemore’s Cove. If Bragg could have written the orders on which this column of Federals was marching, he could not have arranged the situation any more favorably for himself and his army. The Union division was temporarily isolated from its comrades still atop the mountain but only an easy ten miles from Bragg’s main point of concentration at La Fayette. Confederate forces found themselves perfectly positioned to strike the Federals simultaneously in the front and flank with overwhelming force. Better still, McLemore’s Cove was open to the northeast, thus easily admitting Bragg’s flanking column, but the cove was closed on the south, forming a cul-de-sac as if perfectly designed for trapping overaggressive Yankees.

Bragg immediately issued the orders that should have brought his army clamping down like the jaws of a nutcracker on the front and flank of the Union division, and over the next day and a half he reiterated them with increasing emphasis—all to no avail. Once again the dysfunctional high command of the Army of Tennessee came to the aid of the advancing Federals. Two of Bragg’s generals, Daniel Harvey Hill and Thomas C. Hindman, balked; produced a string of excuses; and finally refused to carry out Bragg’s orders. The Federals, who were in fact the vanguard of the Fourteenth Corps, finally discovered their danger and withdrew unscathed to the crest of Lookout. Too many of the Army of Tennessee’s generals had in their self-seeking combined to convince each other and many of their comrades that Bragg was so hopelessly incompetent that any order he gave had to be a disastrous mistake just because he gave it. The result in McLemore’s Cove had been the loss of what one of Bragg’s staff officers described as an opportunity “which comes to most generals only in their dreams.”

1

Yet even with the opportunity in McLemore’s Cove gone, Bragg’s position was still amazingly good. With his army concentrated around La Fayette and steadily increasing as reinforcements arrived, he was closer to each of Rosecrans’s three separate corps than any of them was to one of the others. Centrally located and with good roads at his disposal, Bragg could strike at Union columns too weak to meet his massed troops and too widely separated to support each other. On September 12 Bragg accordingly issued orders for his troops to strike the isolated Twenty-First Corps, which had been moving south from Chattanooga as Rosecrans’s left wing. Again a Confederate general, this time Leonidas Polk, refused to carry out Bragg’s orders, and the opportunity went begging.

Over the course of the next week Rosecrans, at last aware of his danger, strove to draw his columns together and reunite his army, sidling the Twentieth and Fourteenth corps northward to join and ultimately leapfrog past the Twenty-First Corps’s position near Lee and Gordon’s Mill, where the main Chattanooga–La Fayette Road crossed Chickamauga Creek. Meanwhile Bragg awaited the rest of his reinforcements and did some sidling of his own, sliding his army north opposite Rosecrans’s. If Bragg could move faster than his adversary, he could get north of the Federals and then lunge west, blocking their path to Chattanooga and positioning his army to drive the outnumbered bluecoats southward toward the open maw of McLemore’s Cove, from which the Army of the Cumberland could not hope to escape.