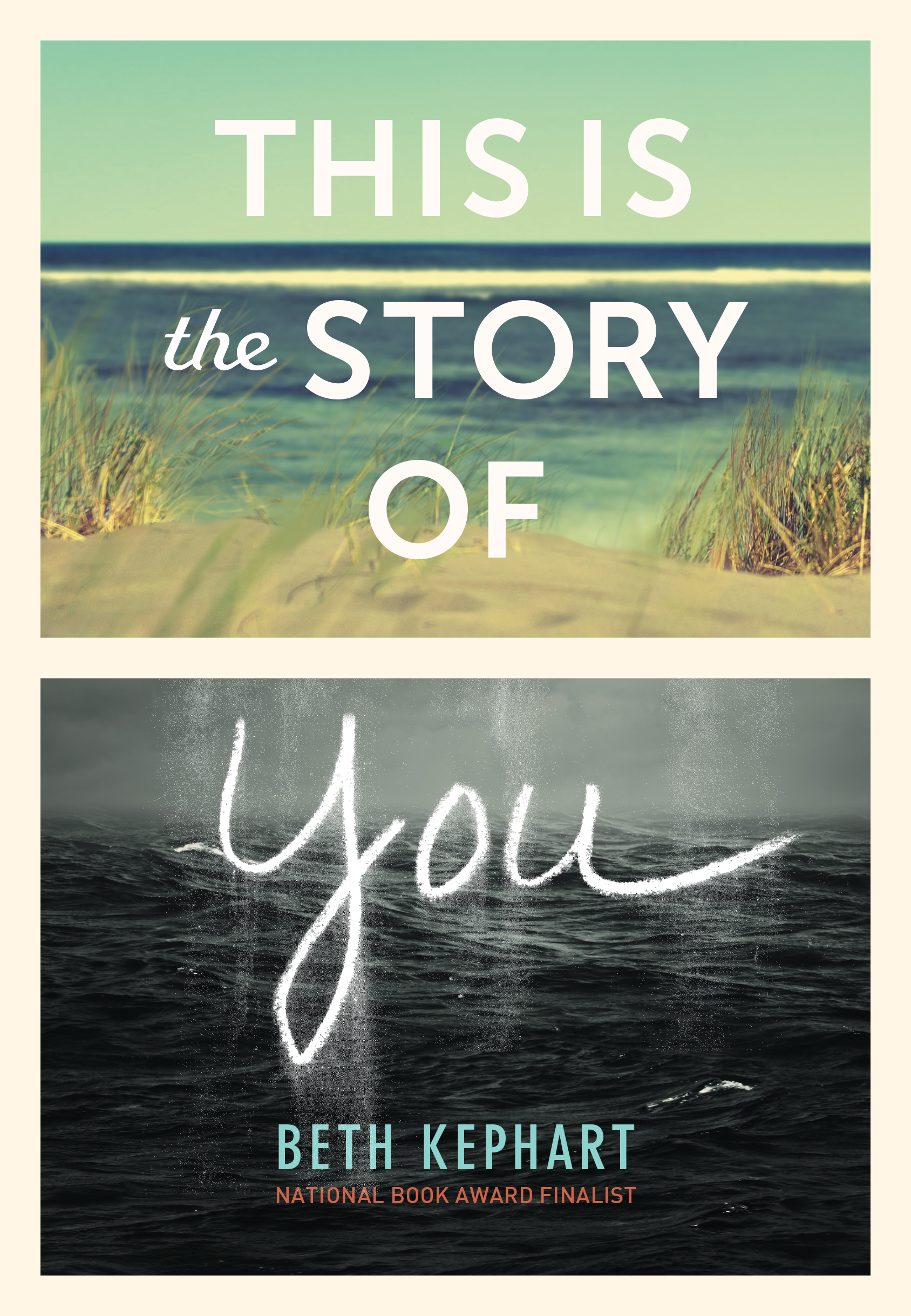

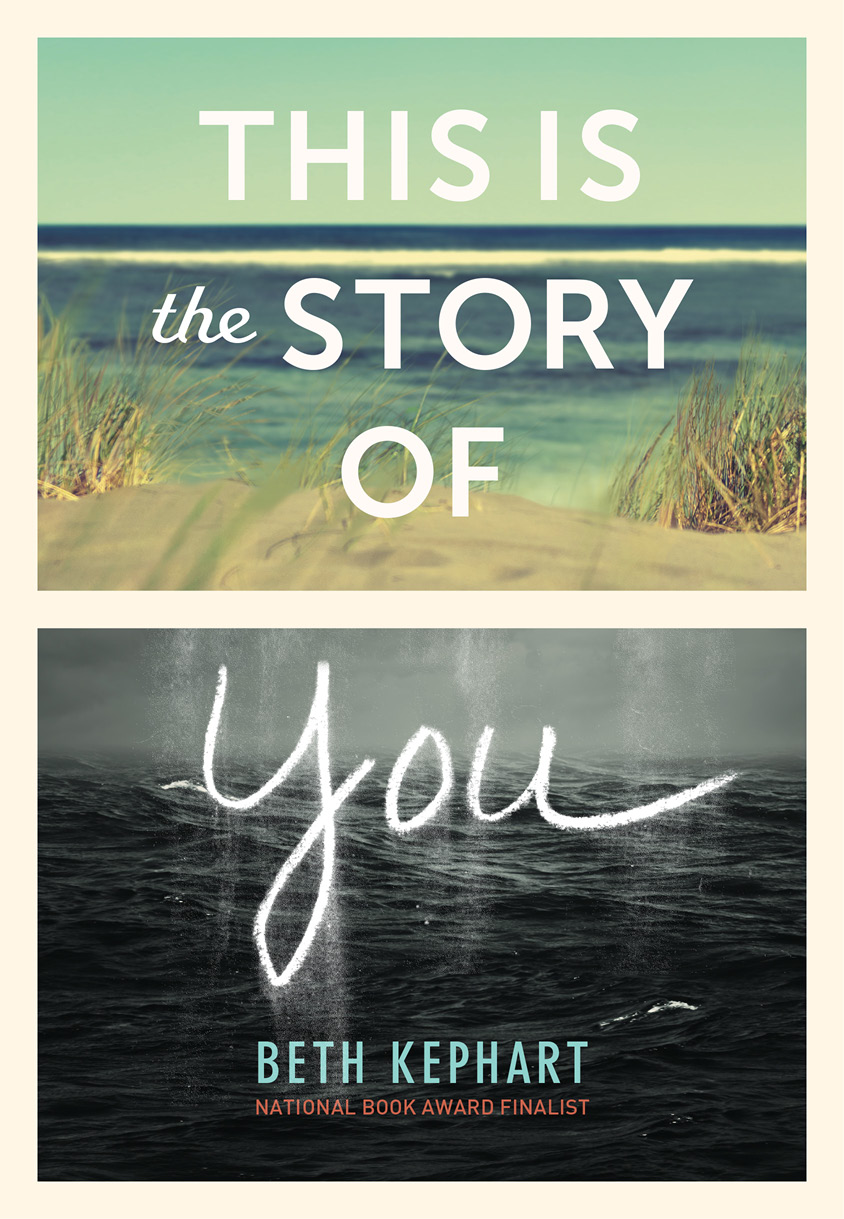

This Is the Story of You

Read This Is the Story of You Online

Authors: Beth Kephart

Copyright © 2016 by Beth Kephart.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Kephart, Beth, author.

This is the story of you / Beth Kephart.

pages cm

Summary: Seventeen-year-old Mira lives in a small island beach town off the coast of New Jersey year-round, and when a devastating superstorm strikes she will face the storm's wrath and the destruction it leaves behind alone.

ISBN 978-1-4521-4284-5 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4521-4652-2 (ebook)

1. HurricanesâNew JerseyâJuvenile fiction. 2. IslandsâNew Jerseyâ

Juvenile fiction. 3. SurvivalâJuvenile fiction. 4. New JerseyâJuvenile fiction.

[1. HurricanesâFiction. 2. IslandsâFiction. 3. SurvivalâFiction. 4. New

JerseyâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.K438Th 2016

813.54âdc232015003765

Design by Jennifer Tolo Pierce.

Typeset in ITC Giovanni.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History.

New York: Henry Holt, 2014.

Joyce, James. The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

New York: B. W. Huebsch, 1916.

“Pelorus Jack.” Lyrics by P. Cole, music by H. Rivers.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

Chronicle Booksâwe see things differently. Become part

of our community at www.chroniclebooks.com/teen.

For my father, brother, and sister,

and in loving memory of my mother,

my grandmother, and Uncle Danny.

Once the beach was ours.

Blue, for example.

Like the color the sun makes the sea. Like the beach bucket he wore as a hat, king of the tidal parade. Like the word

I

and the hour of nobody awake but me. I thought blue was mine, and that we were each ourselves, and that some things could not be stolen. I thought the waves would rise up, toss down, rinse clean, and that I would still be standing here, solid.

I was wrong about everything.

In the beginning it was just the beginning. The storm had no name. It was far away and nothing big, mere vapors and degrees. It was the middle-ish of September. Empty tables in restaurants, naked spaces in parking lots, cool stairs in the lighthouse shaft, no line for donuts, deer in the dune grass, padlocks and chains at the Mini Amuse, the Ferris wheel chairs tipping and dipping.

The beach belonged to Old Carmen and the campfire nobody stopped her from lightingâfour logs and a flame and the sea. The beach belonged to the retrievers and the one collie and the mutts who limped behind, yapping like they thought they could someday take the lead. You could watch the sky, and it was yours. You could stand on the south end of the barrier beach and see Atlantic City blinking on and off like a video game. You could ride your wheels home, and the

splat splat

on the wide asphalt was your sweet siren song.

Everything calm. Nothing headed toward crumble.

September, like I said.

Middle-ish. Skies so sweet and so Berry Blast Blue that Eva and Deni and I and the rest of us at Alabaster were taking most of our classes outside, our Skechers untied and our bodies SPF'd cloud high.

Science was bird-watching in the dunes. English was Trap the Metaphors. History was lessons on Pompeii under the shade of the schoolyard tree. Math was Algebra 2 taught at the picnic tables whose splintery legs were screwed in tight to the concrete pad in the school's backyard, the school that looked like a bank because once it

was

a bank, the big, round, metal eye of its abandoned vault still in the basement.

Our liberty projects were our Project Flowsâour four-year independent studies. Water: that was the category. Subtopic: anything we chose. Monsters of the Sea. Vanishing Cities. Shore Up. Glaciers on the Run. The Murder of Mangroves. We chose our topics. We wrote our books. We understood that on graduation day we would leave those books behind.

Let the process define you.

Our principal, Mr. Friedley, was mayor material, this guy with fresh ideas who believed in straying from the path.

We learn wherever we open our eyes.

That was his motto.

Know the possibilities.

He said that, too.

Don't give up on the future.

Give everything you have. Know who you are. Go forth and

conquer.

We were six miles long by one-half mile at Haven. We'd conquered the place infinities ago.

We were The Isolates. We were one bridge and a few good rules away from normal. We were casual bohemians, expert scavengers, cool.

Woo-hooo,

we said, when the last Vacationeers drove off, over the bridge, Labor Day Monday.

Rumble rumble.

See you next May.

And then out we'd come with our Modes, which were yard-sale vintage, to take back what was ours.

Eva's Mode was a 36-inch Sims Taperkick that she'd decoupaged-out with Betty Boop; that skateboard could flyâEva's three braids going up and down on her back, each like a stick on a marching band drum. Deni had a Gem Electric golf cart, circa 1999âa cute little two-seater that she'd painted gold as the eye of a tiger. Gem was a gift from Deni's uncle. She drove it everywhere, slipping her aviators to the top of her head, where they remained, like a helmet. Deni even swam with those glasses on. She wore them in the rain. She walked around with two pools of reflected sky on her head.

My Mode was a pair of old-time roller skates whose clanking key I wore at my neck like a charm. It was the prettiest jewel you'd ever seen, that key. It left a bruise on my chest from all the thonking, a proud purple thing.

I'm medium everythingâblond, built, smart. But with that key and those strap-them-on adjustables I was such pure speed that Eva would say, every fifth or seventh day, that I should pack for the Olympics already.

Yeah, right, is what I said. Yeah, right. I'm not going anywhere. Because I had my business in Haven. I had

responsibilities.

I had my mom, first of allâlong story. And I had a brother, Jasper Lee, who needed me. Seven years younger and perfect, except for one thing: The kid was born with no iduronate-2-sulfatase enzyme, which means he couldn't recycle mucopolysaccharides, which is another way of explaining this lysosomal disease called Hunter syndrome, which is why his face is shaped the way it is, and why he has trouble walking, and why he is losing his hearing and his seeing and I can't help it if you've never heard of it before, because there are only maybe two thousand people with Hunter in the whole wide world. My prime business in Haven concerned my brother, Jasper Lee, who was Home of the Brave to me, whose disease I knew all the long words to, because knowing the names of things is one small defense against the sad facts of reality.

Mid-September, like I said. Outdoor classes, mostly. Old Carmen watching the flickering sea, the moon in the water, the flames around her campfire logsâall sizzly. Old Carmen, a Haven legend: Someone should have done their Project Flow on her. Sitting like a sea lion on her patch of sand, the long line of her fishing pole tossed to the waves, a bucket at her side to help with the catch. Some people said Old Carmen was an heiress. Some people said she was outer space and alien. Some people said she was old. Vacation season, she disappeared. Labor Day through Memorial Day, she was present. Always the same age, the same clothes, the same fishing line, the same bucket. Old Carmen was Old Carmen. We just let her be.

I lived in a seaside cottage. I lived in the attic room on the topmost floor, my own private deck looking out toward the shore, a sliding door between me and the weather. This is how I'd copped a front-row Old Carmen seat and how I was first to see the dawn exploding and how I was the one for whom the dolphins came, slicing their fins through the waves, those dolphins like excellent friends, scientific name:

Delphinus delphis.

I was the first to see the bubble edge of the surf, where the baby clams and blue crabs and foraminifera (ten thousand kinds of foraminifera) sucked back into their hiding after the waves had knocked them through.

Monsters of the Sea. That was my Project Flow. That was me. I was on a first-name basis with the strange and lovely things. Kingdom through phylum through family, genus, species. I was the taxonomy queen.

I had the attic, which was two stories high, and the sliding doors that opened onto the crooked deck, and the deck itself. That deck was like a continental shelf. It stood on four pole legs, tossing a shadow across the yard below, a place we called the Zone. Every part and parcel of the attic and the deck had belonged, once, to my aunt. The tartan blanket, the drainpipe jeans, the penny loafers, the Marilyn Monroe tees, the faux tuxedo jacket, the curio cabinets, and the curiositiesâall hers, once, just as the cottage, once, had belonged to my aunt, until she left it to my mother. “Over to you, Mickey,” my aunt had said, according to legend, but I never knew for sure. I was

in utero

at the time.

Mickey inherited the cottage. I inherited the view, which is to say the sea and the sky, and the day I'm talking about had been spectacular, the air that kind of blue that snaps a shine into the sea and makes every speck of sand look like combusted mirror dust. Jasper Lee had set his alarm for a 7 a.m. he'd never honor. Mickey had been awake before that. I'd been up since five, watching the toss of the sea.

Out on the beach, the news was playing on Old Carmen's radio. The line off her pole glistened like a strand of dental floss. There was a mutt up to its belly fur in a slow wave, and the sea was behaving itself. There are 140 million square miles of ocean in this world. The oceans are mountains and craters and hot vents and tectonics and all uncountable creatures. That morning, I was pondering a time when there was no sea at all, billions of years before now. I was imagining the earth all hot and blustery, all feisty and flames, working like heck to cool itself down, but mostly spewing its hotness like a cauldron. The sea covers seventy-one percent of our planet, but it wasn't here at the planet's start. The sea fell from the skiesâany Alabasteran writing any Project Flow will tell you that. The sea arrived (most of the sea, that's how they teach it here) when the iced comets cometh, when the asteroids tore through the skies and shattered. The sea around us fell down upon us. It took billions more years before we showed up ourselves.

The sea comes and the sea goes.