This Is Your Brain on Sex (31 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

It’s All about Timing

Two months later, in sunny San Diego, I met Komisaruk and Wise at the Society for Neuroscience conference, which gathers approximately thirty thousand neuroscientists to discuss the newest advances in the field. Having created their orgasm time line, they presented the data from my time in the magnet, merged with data from eight other participants, in one of the conference’s poster sessions. And they were doing so with a three-dimensional movie highlighting the time line of brain activation. Call it brain porn—many of the neuroscientists who stopped by to check out the film had no problem doing so. I doubt Komisaruk or Wise would either.

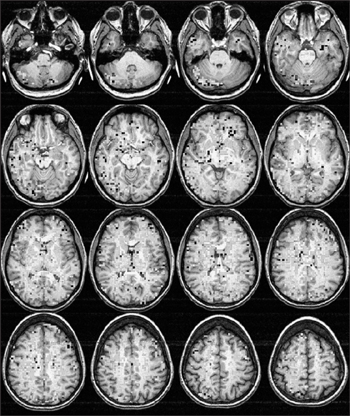

As I watched the film I was struck by the sheer amount of activation. There was a heck of a lot of it. I felt the same way I had when I viewed the composite image of my own brain during orgasm a few weeks earlier. A lot of areas were lit up, the warmest colors indicating the highest levels of activation. It was hard to decipher what it all meant. When I mentioned this observation to Wise, she laughed. “It’s true, there is a lot of activation,” she told me. “An orgasm really is a whole-brain kind of experience.”

My brain at the point of orgasm. As Nan Wise said, it’s a whole-brain kind of experience.

Photo adapted from data recorded by Barry Komisaruk, Rutgers University. Used with permission.

No kidding. The group identified thirty

discrete brain areas activated during self-stimulation to orgasm.

Thirty.

In women, at least, it seems we recruit a whole lot of our brain in order to get a little satisfaction. Given that extensive amount of activation, it can be a little complicated to assess exactly what all those brain areas are doing. However, Komisaruk was able to identify a few distinct areas that lit up before, during, and after orgasm.

What happened in my brain during orgasm? As I roughed up the suspect, so to speak, my genital sensory cortex, motor areas, hypothalamus, thalamus, and substantia nigra lit up. The hypothalamus was no surprise; it has consistently been implicated in all manner of reproductive behaviors, including arousal. The paraventricular nucleus, the part of the brain that produces oxytocin, is located there too. My motor areas controlled my fingers as I self-stimulated, and my genital sensory cortex registered that stimulation. My increasing heart rate could probably be attributed to that cerebellum activation. And the thalamus? It was integrating not only the activity of my wandering fingers but also the memories and fantasies I used

to help build up my arousal. The substantia nigra, an area rich in dopamine-producing neurons, paired with the PVN’s oxytocin release, had me feeling nice and relaxed.

Once I raised my hand to let the researchers know I was at the point of no return, my frontal cortex, that bastion of executive function, came online. Areas implicated in memory, integration of sensory information, and emotion also became active. As my orgasm came to a close, the hypothalamus turned back on, and reward areas like the nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus were now flooded with dopamine. That was what gave me that final rush. The long and the short of it was that Komisaruk and his colleagues saw distinct temporal activity, with different brain areas being recruited as I went from arousal to orgasm and then back around again to rest.

“So did the results end up like you thought they would?” I asked Komisaruk, as a handful of other neuroscientists checked out the poster.

He smiled. “Some things were expected. The sensory regions become activated early on, and then the nucleus accumbens gets activated much later than the other areas. I expected that. But it was interesting: Some areas become active quite suddenly at the onset of orgasm, while others come on very gradually.”

“Suddenly?” I asked.

“The inferior temporal gyrus is one area that comes on suddenly at onset,” he said. “Same with the cerebellum.”

Komisaruk went on to explain that the sudden cerebellum activation may have something to do with muscle tone. It is not a stretch—I tend to clench a bit at orgasm. Okay, maybe I clench a lot. But the inferior temporal gyrus? That is an area usually reserved for higher-level thinking and imagination, maybe fantasy. As far as I can remember, my eyes were shut tight, though I admit I was distracted and can’t say for sure. Even if they were open, there are not a whole lot of compelling items to see inside an fMRI tube. But I was certainly imagining a few things as I achieved climax.

“There’s some kind of cognitive process going on there, though we’re not sure what it is,” Komisaruk told me. “We saw a lot of cortical activation throughout the cortex which has not been reported in other studies.”

One suggestion Komisaruk has for this cognitive process is a kind of inhibition. Perhaps

those instructions to move as little as possible, any internal worries about my moans being overheard in the control room, all the little things I did to overcome my usual squirmy and loud orgasmic tendencies activated my frontal lobe. Or maybe, as I had no one else stimulating me to orgasm, that activation can be attributed to coordinating my own efforts. It is a puzzle yet to be solved.

Wise jumped in with her own revelations. “The process starts with very little activity and then gradually increases. That’s not a surprise. But what was curious to me was that within the brain stem, we saw a lot of different patterns across participants. But there looked like there was a lot of similarity in the cortex. There is something going on there.”

“We all have different kinds of touches that feel good to us,” she continued. “In the future, we need more information about what people are really thinking about while they stimulate and perhaps a little more about what they’re doing to get there.”

An orgasm is an intense experience. Getting to that point involves a variety of cognitive, emotional, and sensory components—even when it’s just you doing the work. Ultimately Komisaruk, Wise, and Whipple hope to understand enough about the different brain areas recruited to help individuals with anorgasmia, that unlucky percentage of women who never have orgasms. They openly admit, however, that we still have a long way to go before we understand the intricacies of it all.

“How do these different brain regions work together? How are they recruited differently in pleasure and pain? What can we learn from women who can think themselves into orgasm in order to help individuals who can’t have an orgasm?” Wise speculated, “I can envision a time when people can regulate their own brain chemistry through some kind of internal process. But we’re still in the infancy. Hell, we’re still in the prenatal in this field. But I can’t wait to see what will come in the next ten years. It’s going to be amazing.”

Though preliminary, the results astonished me. Orgasm is decidedly complex and affects multiple brain systems. I have no doubt researchers like Komisaruk and Wise will spend the rest of their careers trying to figure it out. Even if my postdivorce orgasm count remains on the low side, I can say I have done my part, no matter how meager, to help with the neuroscience.

Chapter 13

A Question of Orientation

The breaking headline as I journeyed

home from Rutgers University after having my orgasm in the fMRI scanner was the tragic suicide of one of the university’s own students, Tyler Clementi. His body had been recovered from the Hudson River that very morning, days after he had jumped to his death from the George Washington Bridge. His suicide was believed to be in response to his college roommate’s posting live webcam footage of him and another male student having sex. This invasive act was apparently the culmination of several bouts of cruel bullying Tyler had faced from classmates because of his sexual orientation.

While I waited in the airline lounge in the hours before my flight home, local and national news shows highlighted the tragedy, along with the recent suicides of several other young gay men across the country. Most of these shows focused on bullying and the role it played in these terrible suicides, but the odd conservative pundit on one show used his airtime to insinuate that Clementi’s death was nothing more than a bad (and perhaps expected) end to an immoral and unnatural lifestyle

choice

.

Joel Derfner is the author of

Swish: My Quest to Become the Gayest Person Ever and What Ended Up Happening Instead

and one of the stars of the Sundance Channel’s reality television show

Girls Who Like Boys Who Like Boys.

When I told him I could not believe that anyone would toss out such views at this time of mourning, he sighed and said, “Sometimes I don’t think they can help themselves.”

1

For decades the West

has debated whether sexual orientation is something you are born with or a lifestyle choice. It is a sensitive and politically charged subject, especially since marriage equality has made its way onto the ballot in several states. Everyone seems to have an opinion about sexual orientation based on religious views, personal experience, or, as more results are published and then publicized, scientific research.

So what does neuroscience have to say about sexual orientation? So far, research suggests that it is determined even before birth. (Please note that bisexuality will not be discussed in this chapter. There has been very little neuroscientific research into this particular orientation, likely because there is such wide variability in behavior across those who identify as bisexual, making it very difficult to study.) “I haven’t seen any evidence to suggest [homosexuality] is a choice at all,” said Qazi Rahman, a researcher who specializes in the psychobiology of sexual orientation at Queen Mary University of London. “Yet the debate goes on.”

To understand why debate continues, we need to take a closer look at the research—what little there is—that has been published. Historically the study of sexual orientation has focused on genes. Twin studies have long suggested that there is a genetic component to which gender a person ends up being attracted to; that is, genetic components are estimated to make up about 50 percent of the different possible variables that influence sexual orientation. However, as much as one might like to herald science as being completely objective, it is influenced by the culture and society of the day.

“People tend to think science is the truth, the end-all, be-all. It’s objective: scientists have a hypothesis and then test it,” said Steve Wiltgen. He is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior at the University of California, Irvine, and an openly gay man. When I met him he had recently presented a poster discussing the history of the neurobiological study of homosexuality at a neuroscience conference. “But the more you look back at the science that’s been done, you see how the questions and the studies fit into the beliefs when that research took place.”

2

Historically, the neurobiological emphasis on so-called gay genes existed because homosexuality was considered a psychiatric disorder; until 1973 it was even listed as one in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

. Remnants of the belief that homosexuality is a type of disease still linger, if not in the scientific studies themselves, certainly in the way much of the general public chooses to interpret them. Clearly, early genetic studies looking at sexual orientation were colored by the idea that homosexuality was a biological mistake that should be undone. With this backdrop in place, some of the earliest work in neurobiology was based on the idea that if a gene or group of genes could be implicated in sexual orientation, there was the possibility of treatment, perhaps even a cure.

“Fruity” Genes

Chances are, if you have ever left your bananas on the kitchen counter for too long, you have seen

Drosophila melanogaster,

the common fruit fly, up close and personal. Fruit flies do appreciate overripe fruit. Though you may think only about ways to exterminate these annoying little insects, they are an animal model of choice for many neurobiologists. Their simple brain offers a good gauge to test a host of neurobiological theories, on topics ranging from learning to memory to sexual function. The history of the neurobiology of sexual orientation begins with this prototype.