This Side of Jordan (24 page)

Read This Side of Jordan Online

Authors: Monte Schulz

“I was discouraged from even considering it,” the dwarf replied. “I'd given thought to writing stories for the

Hadleyville Journal

when I was as young as thirteen, but Auntie told me if I sold even one, my photograph would be published by the paper the next day and she'd become the laughingstock of the community, and might even draw attention from the Eugenics Society. I did grow many wonderful tomatoes and green beans in my garden that Auntie sold at market, but Bessie and Pleasance told me later that she always maintained they'd come down river by steamboat from her cousin Percival J. Miner's garden in Festus. I didn't care. More important to me was that people had actually thought enough of what I had grown to buy it and serve it in their homes. The very idea pleased me no end.”

Alvin walked ahead maybe a dozen yards or so, studying the sky for rain clouds and crows, tracing with his shoes wagon ruts in the old dirt road. He figured they had walked a couple miles now since leaving the tourist camp. Though the air was cool in the wake of the storm's passing, the sun was rising higher on the morning sky and before long the road would be warm and the walking more difficult. He was surprised that no truck or automobile or haywagons had come by for so long. He looked back for the dwarf and saw him resting on the suitcase. Rascal wasn't like anyone Alvin had ever met before. He seemed to be some character out of a tall tale spun around a campfire at night when everyone had drank too much corn liquor. Sometimes when they were lying out under a tree in the dark beside Chester's automobile, trying to get a little sleep, Alvin would look over and see the dwarf staring up at the stars, a silly sort of grin on his face, his lips curled back exposing his big teeth, and Alvin would wonder if the dwarf knew more about driving around to strange towns and doing what they were doing than he ever let on.

The farm boy slowed his walking to a casual stroll. Allenville was still a mile or so ahead and the sun was rising higher in the summer sky. He watched the dwarf strain to lift his small suitcase. A day ago, Alvin would have been happy to see him suffer, but this morning he felt sorry for him. He called back to Rascal, “Want me to carry that?”

“No, thank you,” the dwarf replied. “It's my responsibility, although I believe I'm developing a blister on my palm.”

“Those'll kill you.”

“I've had my share, thank you. I'm sure I'll survive.”

“Suit yourself.”

Â

Half an hour later, the farm boy and the dwarf reached the south side of town. The dirt road gave way to plank sidewalks and tall leafy poplars providing shade. Most of Allenville looked plain and ugly, bleached of life and color by the wind and weather off the Iowa prairie.

“I don't believe I can walk any farther this morning,” the dwarf said, dropping his suitcase. His red face was sore with fatigue and sweat beaded up on his brow and stained his romper about the armpits. He looked bedraggled. “Perhaps we ought to rest a while.”

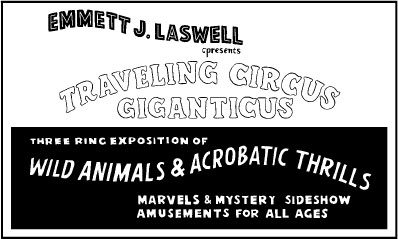

Alvin saw a circus poster nailed to a telephone pole across the street in front of a motor garage and a telegraph office, and went over to have a look.

The poster was still grimy and damp from the evening rainstorm and the dates had been torn away, so Alvin was left to guess when the traveling circus had actually made its appearance in Allenville.

“A circus,” the dwarf remarked, circling the pole. “How wonderful.”

“It ain't here no more,” Alvin said, trying to get the poster off the pole. He put his own suitcase down and stuck his fingernails under the wire staples and popped one of them loose.

“I love the circus,” Rascal said. “Uncle Augustus took me to Hagenbeck-Wallace when I was young. We were given a tour behind the scenes to see how the performers actually lived while on the road. I remember being quite impressed. Everybody was very kind to me and presented both Uncle Augustus and myself with souvenirs before we left.”

“What kind of souvenirs?”

“I don't exactly recall, but I'm sure they were lovely.”

“Well, I won me a prize once at a carnival throwing darts when I was six years old,” said Alvin, prying free another section of the poster. “I still got it, too. A genuine Injun tomahawk from Custer's Last Stand.”

“That's nice,” said Rascal, as he bent down to collect one of the staples Alvin had popped off the pole. He stuck it into his romper and snapped the pocket closed. “Actually, now that you mention it, I do recall winning a fine crystal vase on the midway by pitching lead slugs into several open milk bottles. The circus people told me that nobody had ever done so well at that particular game. I might've been given a ribbon as well, but I couldn't say for certain. I felt quite proud, regardless.”

“Sure you did,” said Alvin, tearing loose the last two corners of the poster from the telephone pole. He read it over carefully once more, then folded the poster into quarters and slipped it under his shirt. “Well, I'd sure like to go see the circus again. I ain't been to one since I was a kid. I remember my daddy telling me how them bearded ladies give you the evil eye if you look at 'em wrong, and once they give it to you, your brains are scrambled the rest of your life and you ain't good for nothing but raking leaves. Maybe we ought to find out where this circus went and follow it down the road. It couldn'ta gone too far.”

“Perhaps we could make the suggestion to our companion. Everybody loves a good circus,” the dwarf said. “Why, even Auntie shared a belly laugh during the clown act last time we went, and ordinarily she has no sense of humor at all.”

“I'd like to go,” said the farm boy, growing an enthusiasm for the idea. “I won't deny it.”

“Then I vote we ought to. It's settled.”

“We'll see.”

They headed down to the end of the alley at the fenceline that bordered the fields surrounding Allenville, then turned west and walked on for another quarter of a mile or so down a long country lane until they heard hymns from the church at the crossroads just outside of Allenville. In a bell tower atop the steeple, a flurry of sparrows chattered. Whitewash had flaked away from the siding, and a quarter of the shingles were missing on the main roof. Sections of the stained glass along the upper windows were also cracked and in danger of falling out.

“They ought to at least paint it,” Alvin remarked, giving the church a good once-over from across the road. “Don't seem right to let it go like that.”

“I suppose they haven't the resources,” the dwarf replied. “I painted our back porch one day when Auntie was off on errands and was shocked to discover how much everything cost. Had Auntie seen the bill, I doubt she'd have allowed it.”

“I guess a church'd be able to afford it,” Alvin said. “They don't do nothing except collect money.”

“Do you attend often?”

“Not if I can help it.” He hated church and didn't ever read the Bible. It was all baloney.

Alvin listened to the singing.

Â

There's a land that is fairer than day, and by faith we can see it afar

For the Father waits over the way, to prepare me a dwelling place there

In the sweet (in the sweet) by and by (by and by)

We shall meet on that beautiful shore (by and by)

Â

Rascal said, “Auntie and I attended services every Sunday morning together until I turned twenty. We went by hired carriage and greeted each of our fellow Christians by name along the route. It made for quite a spectacle, I must admit.”

Â

To our bountiful Father above, we will offer our tribute of praise,

For the glorious gift of His love, and the blessings that hallow our days.”

Â

The dwarf added, “It was also one of the few occasions where she allowed herself to be seen with me out of doors. At the church, we had our own special place reserved in the front pew and two fine leatherbound volumes of the hymnal.”

Â

In the sweet (in the sweet) by and by (by and by)

We shall meet on that beautiful shore (by and by).

In the sweet (in the sweet) by and by, (by and by)

We shall meet on that beautiful shore.

Â

“Singing's the worst part of going to church,” said Alvin, listening to the hymn. “Any old bunch of billygoats'll sound about as good as most folks trying to carry a tune.”

“I was elected to the choir,” Rascal said, “though, of course, Auntie did not permit me to perform for fear I'd embarrass myself in front of our neighbors.”

“I hope you thanked her.”

“In fact, her fears were quite unfounded. My voice back then possessed near perfect pitch and I'd long since committed all our hymns to memory. I'm sure my performance would have been memorable.”

Â

We shall sing on that beautiful shore, the melodious songs of the blest

And our spirits shall sorrow no more, not a sigh for the blessings of rest.

In the sweet (in the sweet) by and by (by and by)

We shall meet on that beautiful shore (by and by).

Â

Alvin stuck his suitcase in the weeds and crossed the road to the side of the church and looked in through the yellow windowpanes. The pews were packed with people dressed in their Sunday finest. At the pulpit, the preacher was lecturing hellfire and brimstone while the choir behind him nodded grimly. It didn't seem all that different from services Alvin had attended in Farrington. Singing and shouting. Lots of old people acting drowsy, small children getting pinched by their mothers for fidgeting too often. Who paid any mind to what some dumbbell preacher had to say? When Alvin first caught the consumption, Reverend Newbury came to the farm and took his hand and told him Jesus dwelt in his lungs and if he kept faith in the Lord, Jesus would do his breathing for him until the Holy Spirit healed that awful disease. A month later Alvin was in the sanitarium, nearer to heaven than health.

The farm boy stepped down from the window and looked around. He and the dwarf seemed to be the only people nearby not inside the church. Somehow it made him feel truant and guilty, like he ought to go indoors and sit down, maybe sing along for a few minutes or so. Rascal walked along the road a little further, studying a patch of Arkansas rose growing at the foot of the fence that bordered the fields next to the church. Probably the dwarf wouldn't be allowed inside a church with normal folks, Alvin thought, on account of a case like his would make the Lord look bad. Then again, maybe the preacher would just hold Rascal up as an example of what can happen if you don't go to church or say your prayers at bedtime. Being born a dwarf might even be the mark of Cain, for all anyone knew, God's judgment on a wicked man or woman for sins unforgiven. Aunt Hattie always said the Lord worked in sly and secretive ways. He knew everything you ever did, and everything you planned to do, and though you might fool Him now and then, when the last card got thrown down, you'd always know His hand was the strongest. Alvin watched the dwarf pick a handful of purple asters and fold them into his fist for carrying alongside the small suitcase. Somewhere along the line, Rascal's family must have earned the Lord's attention in a powerful way.

How well we bear our burdens

, Aunt Hattie had told Alvin,

marks us in the Lord's countenance, for it was He who bestowed them, after all.

“It's a beautiful day, don't you agree?” said the dwarf, walking toward Alvin. He offered a wildflower, but the farm boy declined.

“I already told you, I'm allergic.”

“Then I'll keep them myself for luck,” Rascal said, tucking a blossom into his romper before scattering the remaining handful into the wildrye next to the church. “God smiles on Sundays. I can hardly recall one where it rained.”

“Maybe we ought to go inside,” Alvin said, tired of waiting around outdoors. He'd like to have been able to stretch out in the back row on a long pew and have a nap. Truth was, he was beginning to think he would have to see a doctor sooner than later.

“Do you think that would be wise? Chester was most specific in his request that we wait until service lets out.”

“Well, I ain't standing here all morning.”

“I don't mind waiting,” the dwarf replied. “Impatience is the devil's lure.”

“Shut up.”

The dwarf crossed back over the road and picked up his suitcase. Alvin walked around to the rear of the church to look for the back door. Most of the conveyances people had used to travel to the church were parked there, scattered about in no particular order, old buggies and motorcarsâincluding Chester's tan Packard. There was only a short section of fence along the north end of the church separating the lot from the surrounding fields, and most of the horses hitched to the buggies stood in the morning sun, grazing where grass was long enough. As Alvin drew nearer, he saw a homely young girl with stringy brown hair sitting on a wooden fifteen-gallon water bucket, a tattered Bible in her lap. She was fiddling with a partially unraveled ball of lavender yarn, a cat's cradle. The girl's plain thin face was pale as powder and her print dress thread-worn and dull.