This Side of Jordan (5 page)

Read This Side of Jordan Online

Authors: Monte Schulz

Chester shut the engine off and climbed out. “You thirsty, kid? There's a lunchroom right around the corner. Come on, I'll set you up to an ice cold dope.”

Alvin grabbed his cap and stepped out of the car. The sun was warmer than ever. Most of his family had the constitution for heat; his sisters sat indoors in the kitchen until high noon, then went out past the barn to play dolls in the tall grass meadows while he'd be hiding under an old shagbark hickory whenever he wasn't working, keeping to the shade. The family said it was his red hair that made him burn. Fishing at the river with Frenchy, he had to wear a floppy hat and a long-sleeved shirt buttoned to the collar. The hat made the girls along the shore think he was bald. He already suffered his affliction; now he had the hat, too. It was humiliating.

My dear son, we all have our crosses to bear,

his mother told him, but what did she know? She worked in her garden everyday and hardly ever needed a sunbonnet.

The attendant came out of the filling station, a freckle-faced towhead hardly older than Alvin himself. “What'll it be, fellows?”

“Shoot some gasoline into our tank,” Chester said, handing the boy a couple of dollar bills.

“Yes, sir.”

“We'll be back in about ten minutes.”

“Yes, sir.”

Chester gave Alvin a nudge. “Let's go, kid.”

They entered a narrow one-room building across the street where three men in suspenders and blue overalls sat hunched over a game of checkers at a table by the front window. The one kibitzing was smoking a three-for-a-nickel stogie and held a punchboard on his lap. Except for the old fellow in the white chef's hat, reading box scores from the morning sport sheets beside the cash register, they were the only people in the building. Six empty tables were arranged along one wall parallel to a short order counter that ran from the front of the building to the rear. Chester chose a seat at the table next to the back door. Alvin took the chair across from him and studied the lunch program hung on the wall behind the cash register: meatloaf, lamb, beefsteak, roasted chicken, baked ham and tomato soupâeach dinner for 50¢.

“Do we have time to eat?” he asked, feeling a queasiness in his stomach that was either nervousness or hunger, probably both. He'd crammed down five hardboiled eggs, smoked bacon, a plate of toast and three cups of coffee for breakfast, but was already hungry again. His appetite was strange since he had gotten sick. Some days he never felt like eating a bite; the next day he couldn't keep his belly quiet.

“Nope.” Chester took a package of Camel cigarettes from his vest pocket. He called to the man at the cash register. “Say, dad, how about a couple of Coca-Colas?”

The old fellow nodded and went to get the drinks from an icebox under the counter. They had drawn the attention of the men playing checkers. Chester lit his cigarette and gave them a friendly wave. The old fellow in the chef's hat brought two opened bottles of Coca-Cola and set them down in front of Chester. “That'll be ten cents, please.”

Chester dug into his trousers and came up with a nickel and a handful of pennies which he sprinkled out onto the counter. “Take your pick.”

After the fellow had gone, Chester took a sip from one of the Coke bottles. “See those three onionheads over there by the window?”

Alvin nodded. In fact, he had been trying to ignore them. He didn't know much about folks in Missouri and what they thought of strangers. Were they friendly here?

“Well, I'll lay they're trying to figure out whether we're bootleggers or drugstore cowboys,” Chester continued, “and we both know they couldn't tell a bootlegger from Hoover's grandmother. But what they're worried about are their birdies. That is, whose we'll be loving up this afternoon and whose we'll be ignoring. Trust me, kid. Losing their dames is the first thing folks get muddleheaded over when fellows like us come into town. We could go out and rob them blind, and while they'll be plenty sore, they'll start forgetting about it in a month or so. But if we were to drive off into the sunset with a couple of Hadleyville's sweeties, they'd hunt us down like animals, shoot us full of holes, and cut our carcasses up for the hogs.”

Four more men wearing denim overalls came into the lunchroom and said hello to the old fellow at the cash register and took the table beside the checker players. One of them looked over at Alvin and Chester, and murmured a few words to the fellow beside him. The others seated at the table began talking among themselves.

Chester leaned across to the next table and grabbed an ashtray for his cigarette. Alvin felt a bellyache coming on. Chester had brought him here to Hadleyville to help him take some money out of the First Commerce Bank on Third Street. He'd told him so just after breakfast when he paid the bill. “

It'll be easy as pie,

”

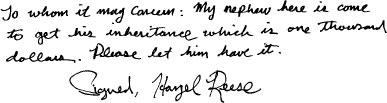

Chester said, handing Alvin a note that read:

“

You're going to present this to one of the tellers,

”

he said.

“

Don't joke me,

”

Alvin replied.

Chester laughed and told him to get into the car because they had to reach Hadleyville by noon.

“

Don't worry, kid,

”

Chester said, while they were driving along the highway.

“

You'll make the grade, all right.

”

Alvin asked, “You sure we ain't got time for a couple of pork chop sandwiches? I'm awful hungry.”

Chester took a quick drag off the cigarette. “I'm sure.”

His eyes were bluer than any Alvin had ever seen. He shaved each morning. Smelled like cologne. Wore fresh collars and a swell suit. Had his shoes shined before breakfast. Smiled at everyone he met. Never seemed scared, neither, Alvin thought. Now that was something worth learning. He could do a lot worse than taking after a smart fellow like Chester Burke.

A raucous cheer came from the checker game as somebody won. The old fellow at the cash register clapped. Out on the sidewalk, two rag-tag boys on bicycles rode past carrying fishing poles. Alvin felt envious; that's where he ought to be going. He could probably show 'em a good thing or two. The twelve o'clock whistle at the shingle mill across town shrieked, signaling the noon hour.

Chester snuffed out his cigarette, then drained the last of his Coca-Cola. “Let's go, kid.”

Alvin studied the men at the checker game. Did they have any suspicions? Before today, he hadn't done more than carry Chester's suitcases for him and sit around the hotel lobby in New London while Chester finished his appointments; after changing a flat tire at Hannibal, Alvin didn't even have to leave his room. Ten dollars a day he'd earned, seventy dollars since the dance derby, more dough than he'd had in his hand all year. Once he hit a thousand dollars, he could buy his own motor and get a shoeshine every morning, too.

Out on the sidewalk, Alvin asked Chester, “You ain't going to cut me out, are you?”

A black Essex sedan rushed by toward the downtown.

Chester smiled. “Of course not, kid. I'm a square shooter. Trust me. There'll be kale enough for the both of us, you'll see.” He stared up the street toward the middle of town while lighting another cigarette.

Alvin watched a group of women come out of Bogart's Grocery Emporium, burdened with packages. They were smiling brightly. Another automobile went by and a dog chased across the street, barking in its dusty wake.

The farm boy followed Chester back up the sidewalk to the Dixie filling station where he bought a stick of chewing gum to settle his stomach. When he came out again, Chester reached into the backseat of the Packard for a gray brim hat and gave it to Alvin. “Here, put this on.”

Alvin frowned, but took off his checked cap and tried the hat on. It felt tight. He looked across at the garage window to see his reflection. He shook his head. “It don't fit. I prefer my own better.”

He took it off.

Chester said, “Put it back on. You'll wear it to the bank. Throw the other one in the car.”

“Well, what's it all about?”

“It's part of the gag.”

“Oh.”

Chester grabbed Alvin's cap and tossed it into the Packard, then climbed in behind the wheel. Before Alvin could get around to the passenger side, Chester stopped him. “You're going to have to walk there. It's only a few blocks or so. This is First Street. Follow it to Chapman, take a left, go to Sixth, take another left. You'll see it on the corner by the town square. First Commerce Bank. You can't miss it.” He checked his pocketwatch. “We'll meet inside at a quarter till. Don't be late.”

Then Chester put the car into gear and drove off.

The freckle-faced towhead inside the filling station watched through the plate glass. Alvin gave him the bad eye so he would mind his own business. He hated people staring at him. For half a year after Alvin had come back from the sanitarium, he'd felt like a sideshow freak, people looking at him wherever he went like they'd never seen someone return from the dead. When the towhead pulled a linen shade down against the sun, Alvin really felt alone, so he began walking down the sidewalk past the corner of the lunchroom and across the intersection into the next block of shade trees and modest lumber houses and smaller shanties of corrugated iron that looked more like fancy car garages. He took the stick of gum out of his shirt pocket and stuck it into his mouth. A couple of Fords rattled by. People across the street walked in and out of stores. He ignored them all, pretending like he walked down that sidewalk each day of his life and had every right in the world to be there.

Don't act like a hick that ain't never been to town,

he reminded himself.

Folks notice that. They can tell when you're somewhere you never been before and don't belong.

He chewed vigorously while he walked and held his head up so nobody would think he was timid. He smelled the blossoming home orchards behind the houses and spring flowers that grew beneath butterbean vine along picket fencelines in the shade where the dark earth was damp from recent rainshowers. The concrete sidewalk was cracked here and there, and tufts of grass grew in the fractures. Towering elm trees and poplars and cottonwoods arched overhead. More motorcars passed and the I.G.A. store across the street gave way at Williams Street to a neighborhood of elegantly fretted wood houses and gardens. Alvin heard hose nozzles hissing, piano scales from sunlit parlors, a hammerfall on steel echoing across the warm noon air.

It ain't so bad,

he thought.

Why, a fellow could get used to a new place like this in a hurry if he needed to.

To hell with the farm and everybody treating him like an invalid. He'd thrown all of that over and was done with it. His confidence growing by the minute, the farm boy walked ahead with a fresh bounce in his step.

Two blocks on, Alvin paused in front of a large two-story framehouse whose dry, ratty lawn covered most of the square lot. A lovely magnolia out front, a thick white oak in the side yard, and two black cherry trees toward the back fence provided shade for a lot where nearly everything had died from neglect. Even the paint on the fence pickets out front had peeled and vanished in a drier season, somebody's initials carved into the wood. The place looked abandoned and it wasn't only the lawn. Nearer the house, just under the shade of the magnolia, dozens of children's toys lay broken and scattered in the scruffy weedsâalphabet building blocks, tin bugles, wooden soldiers, wingless aeroplanes. Back along the side of the house where coralberry grew beneath the window boxes, an old tire hung down from the branch of the oak tree on a short length of rope. When they were kids, Alvin and Frenchy would go twirling in a tire they had hung inside Uncle Henry's barn. The stunt was to get as dizzy as possible, then play wirewalker along the tops of the stalls from one end of the barn to the other without falling off. Strolling out of the barn without stinking head to foot from horse manure was considered the game's supreme merit badge.

Feeling adventurous, Alvin opened the gate, keeping an eye on the front door whose screen was still closed, and crossed into the yard, staying under the overlapping shade of the blooming magnolia and the old oak. As he moved along the fence to the rear of the house, the farm boy saw more junk thrown about: cushions, shoes, an old lamp, a wicker chair without its seat, a rusted bed frame, torn pillows. He decided that either somebody had been doing spring-cleaning and had forgotten to bring everything back inside or the people living in the house were hillbillies. He came up to the swing and gave it a shove. The rope curled above the tire and twisted into a mean knot where it looped over the branch. Alvin stared at the house. Lace curtains were hung in the window frames, hiding the interior like a shroud. Back of the house, the trashcan had fallen over, spilling its contents all over the walkway between a tool shed and a weed-eaten vegetable patch.

Now he was curious what the indoors looked like, how high the garbage was piled elsewhere throughout the house. A short porch led up to the back door. If it wasn't locked, well, he might just take a quick peek inside. He walked up to the door and reached for the knob, then stopped to reconsider. If someone came to the door, how would he explain his presence in the back yard? Thinking on his feet was not one of Alvin's greatest strengths. All he could say was that he was lost and needed a drink of water and he'd already tried the front door and nobody had answered so he had come around back. Who could get bitter about a fellow asking for help? Alvin reached for the knob again.