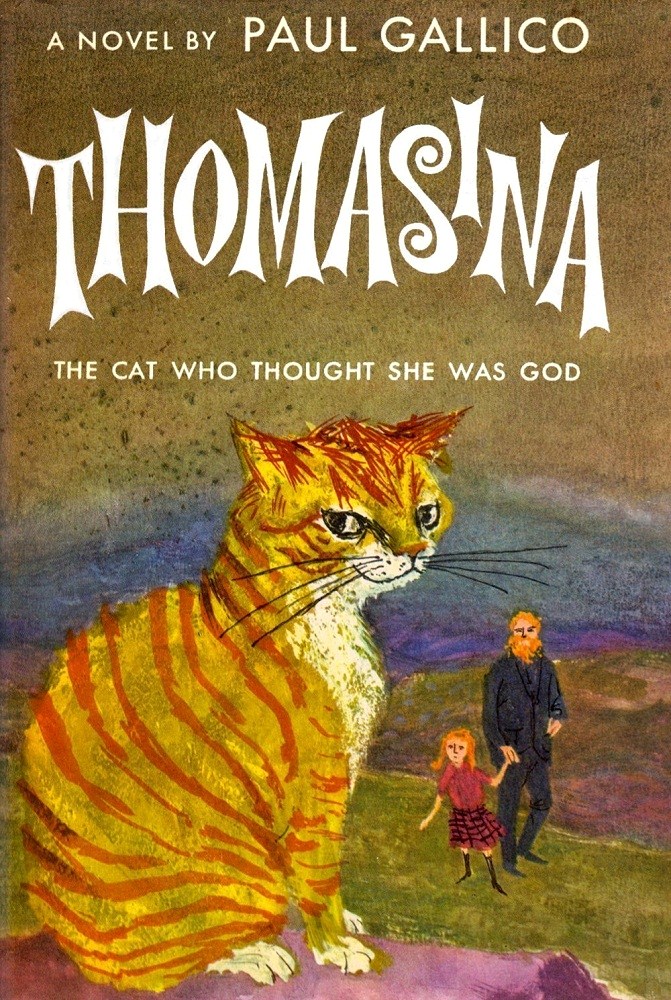

Thomasina - The Cat Who Thought She Was God

Read Thomasina - The Cat Who Thought She Was God Online

Authors: Paul Gallico

Perhaps Thomasina did not really have divine powers. Possibly she was only an ordinary cat. But it cannot be denied that she changed three lives in a near-miraculous manner . . .

There was Andrew MacDhui, Scottish veterinarian, whose bristling manner matched his fiery beard. Dour and withdrawn since his wife’s death, he had little patience with wooing sick animals back to health and was said to be a wee bit too quick with the chloroform.

There was Andrew’s seven-year-old daughter, who brought her ailing cat, Thomasina, to her father to be cured—only to be bitterly disappointed by Andrew’s hasty and unfeeling disposal of her beloved cat.

And there was Lori—beautiful, “daft Lori,” whose gentle and mysterious powers of healing caused some of the villagers to call her a saint—or a witch.

How Thomasina, taking full advantage of a cat’s nine lives, brought these three together is a story which may be enjoyed for its face-value excitement and whimsey, but in which the more discerning reader will find both trenchant allegory and spirit-lifting philosophy.

Set in the rugged and picturesque Scottish highland, Paul Gallico’s latest and finest work, while it retains the elements of faith and enchantment which have long delighted his many devotees, is primarily a novel of romance, character, and high adventure. With superb artistry, the author of The Snow Goose and The Small Miracle blends fantasy and warm humanity into a poignant tale of the natural and the supernatural in

the Enchanted Cat.

Books by Paul Gallico

FAREWELL TO SPORT

ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY

THE SECRET FRONT

THE SNOW GOOSE

LOU GEHRIG—PRIDE OF THE YANKEES

GOLF IS A NICE FRIENDLY GAME

CONFESSIONS OF A STORY WRITER

THE LONELY

THE ABANDONED

TRIAL BY TERROR

THE SMALL MIRACLE

THE FOOLISH IMMORTALS

SNOWFLAKE

LOVE OF SEVEN DOLLS

All of the characters in this book

are fictitious and any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead,

is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 57-13018

Copyright © 1957 by Paul Gallico

Designed by Diana Klemin

Cover and Frontispiece by Gioia Fiammenghi

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

TO VIRGINIA

T H O M A S I N A

1

M

r. Andrew MacDhui, veterinary surgeon, thrust his brick-red, bristling beard through the door of the waiting room adjacent to the surgery and looked with cold, hostile eyes upon the people seated there on the plain pine, yellow chairs with their pets on their laps or at their feet awaiting his attendance.

Willie Bannock, his brisk, wiry man of all work in dispensary, office, and animal hospital had already gossiped a partial list of those present that morning to Mr. MacDhui, including his friend and next-door neighbor the minister, Angus Peddie. Mr. Peddie, of course, would be there with or because of his insufferable little pug dog, whose gastric disturbances were brought on by pampering and the feeding of forbidden sweets. Mr. MacDhui’s glance dropped to the narrow lap of the short-legged, round little clergyman, and for a moment his eye was caught up in the unhappy, milky one of the pug, rolled in his direction, filled with the misery of bellyache, and yet expressing a certain hope and longing as well. The animal had come to associate his visits to this place, the smells, and the huge man with the fur on his face with relief.

The veterinary disentangled himself from the hypnotic eye and wished angrily that Peddie would follow his advice on feeding the animal and not be there wasting his time. He noted the rich builder’s wife from Glasgow on holiday with her rheumy little Yorkshire terrier, an animal he particularly detested, with its ridiculous velvet bow laced into its silken topknot. There was Mrs. Kinloch over the ears of her Siamese cat, which lay upon her knee, occasionally shaking its head and complaining in a raucous voice, and, too, there was Mr. Dobbie, the grocer, whose long and doleful countenance reflected that of his Scots terrier, who was suffering from the mange and looked as though a visit to the upholsterer would be more practical.

There were a half dozen or so others, including a small boy whom he seemed to have seen somewhere before, and at the head of the line he recognized old, obese Mrs. Laggan, proprietress of the newspaper and tobacco shop, who, with her aged, wheezing, nondescript, black mongrel, Rabbie, his muzzle grayed, his eyes rheumy with age, was a landmark of Inveranoch and seemingly had been so for years.

Mrs. Laggan was a widow and had been for the past twenty-five years of her seventy-odd. For the last fifteen of them her dog Rabbie had been her only companion, and his fat form draped across the doorsill of Mrs. Laggan’s shop was as familiar a figure, to natives as well as visitors to the Highland town, as that of the fat widow in her Paisley shawl. Since the doorsill was Rabbie’s place, nose between forepaws, eyes rolled upward, clients of the widow Laggan had learned to step over Rabbie when entering and departing. It was said in the High Street that descendants of these clients were already born with this precaution bred into them.

Mr. MacDhui looked his clients over and the clients looked back at him with varying degrees of anxiety, hope, deference, or in some cases a return of the hostility that seemed to be written all over the well-marked features of his face, the high brow, the indignantly flaring red-tufted eyebrows, commanding blue eyes, strong nose, full and sometimes mocking lips, half seen through the bristle of red mustache and beard and the truculent and aggressive chin.

His eyes and, above all, his manner always seemed cold and angry, perhaps because, it was said in Inveranoch, he was on the whole a cold and angry man.

A widower of the stature and flamboyance of Mr. Veterinary Surgeon MacDhui was subject enough for gossip in a Highland town the size of Inveranoch in Argyllshire, where he had been in practice for only a little over eighteen months. By the nature of his profession he was a figure of importance there, since he looked after not only the personal and private pets of the townspeople, but was responsible also for the health of the livestock raised in the outlying farms of the district, the herds of Angus cattle and black-faced sheep, pigs, and fowl. In addition, he was the appointed veterinary of the district for the inspection of meat and milk and sanitary husbandry as well.

The gossips allowed that Andrew MacDhui was an honest, forthright, and fair-dealing man, but, and this was the opinion of the strictly religiously inclined, a queer one to be dealing with God’s dumb creatures, since he appeared to have no love for animals, very little for man, and neither the inclination nor time for God. Whether or not he was an out-and-out unbeliever, as many claimed, he certainly never was seen in Mr. Peddie’s church, even though the two were known to be good friends. Others claimed that when his wife had died his heart had turned to stone, all but the corner devoted to his love for his seven-year-old child Mary Ruadh, the one who was never seen without that ill-favored, queer-marked ginger cat she called Thomasina.

Mind you, said the tattlers, no one denied that he was a good doctor for the beasties, and efficient. Quick to cure or kill, and a mite too handy with the chloroform rag, was the word that went around. Those who felt kindly toward him held that he was a humane man, not disposed to see a hopelessly sick animal suffer needlessly, while those who disliked him and his high-handed ways called him a hard, cruel man to whom the life of an animal was as nothing, and who was openly contemptuous of people who were sentimentally attached to their pets.

And many of those who did not encounter him professionally were inclined to the belief that there must be some good in the man else he would not have had the friendship and esteem of Mr. Angus Peddie, pastor and guide of the Presbyterian flock of Inveranoch. It was said that the minister, who had known MacDhui in their student days, had been largely instrumental in persuading his friend, upon the death of his wife Anne, to purchase the practice of Inveranoch’s retiring vet and move thither, leaving behind him the unhappy memories that had bedeviled him in Glasgow.

Several of the inhabitants of Inveranoch remembered Mr. MacDhui’s late father John, himself a Glasgow veterinary, a dour, tyrannical old man with a strong religious bent, who, holding the purse strings, had compelled his son to follow in his footsteps. The story was that Andrew MacDhui had wished to study to become a surgeon in his youth but in the end had been compelled for financial reasons to yield to his father’s wishes and likewise become a veterinary.

One of these inhabitants had once paid a visit to the gloomy old house in Dunear Street in Glasgow where for a time father and son practiced together until the old man died, and had nothing good to say about it, except that it was not much to wonder at that Mr. MacDhui had turned out as he had.

Mr. Peddie had known MacDhui’s father as a psalm-singing old hypocrite in whose home God served merely as an auxiliary policeman. Whatever seemed healthy or fun, old John MacDhui’s God was against, and Andrew MacDhui had grown up first hating Him and then denying Him . . . The tragedy of the loss of his wife Anne, when his daughter, Mary Ruadh, was only three, had confirmed him in his bitterness.