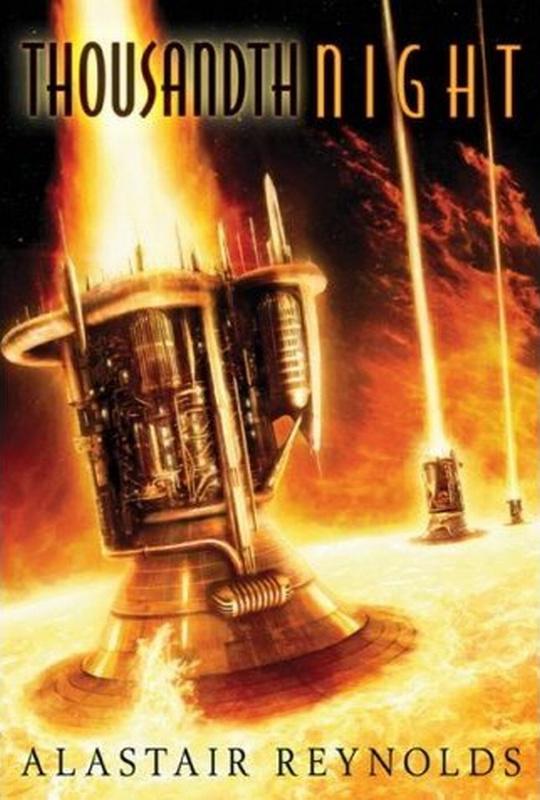

Thousandth Night

Authors: Alastair Reynolds

Thousandth Night

Alastair Reynolds

Originally published 2005

Alastair

Reynolds is a frequent contributor to

Interzone,

and has also sold to

Asimov’s Science Fiction, Spectrum SF,

and elsewhere. His first novel,

Revelation Space,

was widely hailed as one of the major SF books of the

year; it was quickly followed by

Chasm City, Redemption Ark, Absolution

Gap,

and

Century Rain,

all big books that were big sellers as well,

establishing Reynolds as one of the best and most popular new SF writers to

enter the field in many years. His most recent book is a novella collection,

Diamond Dogs, Turquoise Days.

Coming up is a new novel,

Chasing Janus (

published

as

Pushing Ice).

A professional scientist with a Ph.D. in astronomy, he

comes from Wales, but lives in the Netherlands, where he works for the European

Space Agency.

Here

he takes us to a distant future where our remote descendants have become

immortal supermen who possess the powers of gods, for a riveting tale of murder

and intrigue that proves that even for those who have everything, there’s

always a little bit

more

to reach for that’s hanging just out of reach.

. .

It

was the afternoon before my threading, and stomach butterflies were doing their

best to unsettle me. I had little appetite and less small talk. All I wanted

was for the next twenty-four hours to slip by so that it could be someone

else’s turn to sweat. Etiquette forbade it, but there was nothing I’d have

preferred than to flee back to my ship and put myself to sleep until morning.

Instead I had to grin and bear it, just as everyone else had to when their

night came around.

Waves

crashed a kilometre below, dashing against the bone-white cliffs, the spray

cutting through one of the elegant suspension bridges that linked the main

island to the smaller ones surrounding it. Beyond the islands, the humped form

of an aquatic crested the waves. I made out the tiny dots of people frolicking

on the bridge, dancing in the spray. It had been my turn to design the venue

for this carnival, and I thought I’d made a tolerable job of it.

A

pity none of it would last.

In

little over a year machines would pulverise the islands, turning their spired

buildings into powdery rubble. The sea would have pulled them under by the time

the last of our ships had left the system. But even the sea would only last a

few thousand years after that. I’d steered water-ice comets onto this arid

world just to make its oceans. The atmosphere itself was dynamically unstable.

We could breathe it now, but there was no biomass elsewhere on Reunion to

replenish the oxygen we were turning into carbon dioxide. In twenty thousand

years the world would be uninhabitable to all but the hardiest microorganisms.

It would stay like that for the better part of another hundred and eighty

thousand years, until our return.

By

then the scenery would be someone else’s problem, not mine. On Thousandth

Night—the final evening of the reunion—the person who had threaded the most

acclaimed strand would be charged with designing the venue for the next

gathering. Depending on their plans, they’d arrive between one thousand and ten

thousand years before the official opening of the next gathering.

My

hand tightened on the rail at the edge of the high balcony as I heard urgent

footsteps approach from behind. High hard heels on marble, the swish of an

evening gown.

“Don’t

tell me, Campion. Nerves.”

I

turned around, greeting Purslane—beautiful, regal Purslane— with a stiff smile

and a grunt of acknowledgement. “Mm. How did you guess?”

“Intuition,”

she said. “Actually, I’m surprised you’re here at all.”

“Why’s

that?”

“When

it’s my turn I’m sure I’ll still be on my ship, furiously re-editing until the

last possible moment.”

“That’s

the problem,” I said. “I’ve done all the editing I need. There’s nothing

to

edit. Nothing of any consequence has happened to me since the last time.”

Purslane

fixed me with a knowing smile. Her hair was bunched and high, sculpted like a

fairytale palace with spires and turrets. “Typical false modesty.” She pushed a

glass of red wine into my hand before I could refuse.

“Well,

this time there’s nothing false about it. My thread is going to be a crashing

anticlimax. The sooner we get over it, the better.”

“It’s

going to be that dull?”

I

sipped at the wine. “The very exemplar of dullness. I’ve had a spectacularly

uneventful two hundred thousand years.”

“You

said exactly the same thing last time, Campion. Then you showed us wonders and

miracles. You were the hit of the reunion.”

“Maybe

I’m getting old,” I said, “but this time I felt like taking things a little bit

easier. I made a conscious effort to keep away from inhabited worlds; anywhere

there was the least chance of something exciting happening. I watched a lot of

sunsets.”

“Sunsets,”

she said.

“Mainly

solar-type stars. Under certain conditions of atmospheric calm and viewing

elevation you can sometimes see a flash of green just before the star slips

below the horizon . . . ” I trailed off lamely, detesting the sound of my own

voice. “All right. It’s just scenery.”

“Two

hundred thousand years of it?”

“I’m

not repentant. I enjoyed every minute of it.”

Purslane

sighed and shook her head: I was her hopeless case, and she didn’t mind if I

knew it. “I didn’t see you at the orgy this morning. I was going to ask what

you thought of Tormentil’s strand.”

Tormentil’s

memories, burned into my mind overnight, still had an electric brightness about

them. “The usual self-serving stuff,” I said. “Ever noticed that all the

adventures he embroils himself in always end up making him look wonderful, and

everyone else a bit thick?”

“True.

This time even his usual admirers have been tut-tutting behind his back.”

“Serves

him right.”

Purslane

looked out to sea, through the thicket of hovering ships parked around the

tight little archipelago. A layer of cloud had formed during the afternoon,

with the ships—most of them stationed nose down—piercing it like daggers. There

were nearly a thousand of them. The view resembled an inverted landscape: a sea

of fog, interrupted by the sleek, luminous spires of tall buildings.

“Asphodel’s

ship still hasn’t been sighted,” Purslane said. “It’s looking as if she won’t

make it.”

“Do

you think she’s dead?”

Purslane

dipped her head. “I think it’s a possibility. That last strand of hers . . . a

lot of risk-taking.”

Asphodel’s

strand, delivered during the last reunion, had been full of death-defying

sweeps past lethal phenomena. What had seemed beautiful then—a whiplashing

binary star, or a detonating nova— must have finally reached out and killed

her. Killed one of

us.

“I

liked Asphodel,” I said absently. “I’ll be sorry if she doesn’t make it. Maybe

she’s just delayed.”

“Why

don’t you come inside and stop moping?” Purslane said, edging me away from the

balcony. “It’s not good for you.”

“I’m

not really in the mood.”

“Honestly,

Campion. I’m sure you’re going to startle us tonight.”

“That

depends,” I said, “on how much you like sunsets.”

That

night my memories were threaded into the dreams of the other guests. Come

morning most of them managed to say something vaguely complimentary about my

strand, but beneath the surface politeness their bemused disappointment was all

too obvious. It wasn’t just that my memories had added nothing startling to the

whole. What really annoyed them was that I’d apparently gone out of my way to

have as dull a time as possible. The implication was that I’d let the side down

by looking for pointless green flashes rather than adventure; that I’d

deliberately sought to add nothing useful to the tapestry of our collective

knowledge.

By

the afternoon, my patience was wearing perilously thin.

“Well,

at least you won’t be on the edge of your seat come Thousandth Night,” said

Samphire, an old acquaintance in the line. “That

was

the idea, wasn’t

it?”

“I’m

sorry?”

“Deliberate

dullness, to take you out of the running for best strand.”

“That

wasn’t the idea at all,” I said testily. “Still, if you think it was dull. . .

that’s your prerogative. When’s your strand, Samphire? I’ll be sure to offer my

heartfelt congratulations when everyone else is sticking the boot in.”

“Day

eight hundred,” he said easily. “Plenty of time to study the opposition and

make a few judicious alterations.” Samphire sidled a bit too close for comfort.

I had always found Samphire cloying, but I tolerated his company because his

strands were usually memorable. He had a penchant for digging through the ruins

of ancient human cultures, looting their tombs for quaint technologies, grisly

weapons, and machine minds driven psychotic by two million years of isolation.

“So anyway,” he said, conspiratorially. “Thousandth Night.

Thousandth Night.

Can’t wait to see what you’ve got lined up for us.”

“Nor

can I.”

“What’s

it going to be? You can’t do a Cloud Opera, if that’s what you’ve planned. We

had one of those last time.”

“Not

a very good one though.”

“And

the time before that—what was it?”

“A

re-creation of a major space battle, I think. Effective, if a little on the

brash side.”

“Yes,

I remember now. Didn’t Fescue’s ship mistake it for a real battle? Dug a ten

kilometre wide crater into the crust when his screens went up. The silly fool

had his defence thresholds turned down too low.” Unfortunately, Fescue was in

earshot. He looked at us over the shoulder of the line member he was talking

to, shot me a warning glance then returned to his conversation. “Anyway,”

Samphire continued, oblivious. “What do you mean, you can’t wait? It’s your

show, Campion. Either you’ve planned something or you haven’t.”

I

looked at him pityingly. “You’ve never actually won best strand, have you?”

“Come

close, though . . . my strand on the Homunculus Wars . . . ” He shook his

head. “Never mind. What’s your point?”

“My

point is that sometimes the winner elects to suppress their memories of exactly

what form the Thousandth Night celebrations will take.”

Samphire

touched a finger to his nose. “I know you, Campion. It’ll be tastefully

restrained . . . and very, very dull.”

“Good

luck with your strand,” I said icily.

Samphire

left me. I thought I’d have a few moments alone, but no sooner had I turned to

admire the view than Fescue leaned against the balustrade next to me, swilling

a glass of wine. He held the glass by the stem, in jewelled and ringed fingers.

“Enjoying

yourself, Campion?” he asked, in his usual deep-voiced, paternalistic, faintly

disapproving way. The wind flicked iron-grey hair from his aristocratic brow.

“Yes,

actually. Aren’t you?”

“It’s

not a matter of enjoyment. Not for some of us, at any rate. There’s work to be

done during these reunions—serious business, of great importance to the future

status of the line.”

“Lighten

up,” I said under my breath.

Fescue

and I had never seen eye to eye. Among the nine hundred and ninety-three

surviving members of the line, there were two or three dozen who exerted

special influence. Though we had all been created at the same time, these

figures had cultured a quiet superiority, distancing themselves from the more

frivolous aspects of a reunion. Their body plans and clothes were studiedly

formal. They spent a lot of time standing around in grave huddles, shaking

their heads at the rest of us. They had the strongest ties to external lines.

Many of them were Advocates, like Fescue himself.

If

Fescue had heard my whispered remark, he kept it to himself. “I saw you with

Purslane earlier,” he said.

“It’s

not against the law.”

“You

spend a lot of time with her.”

“Again

. . . whose business is it? Just because she turned her nose up at your elitist

little club.”

“Careful,

Campion. You’ve done well with this venue, but don’t overestimate your

standing. Purslane is a troublemaker—a thorn in the line.”

“She’s

my friend.”

“That’s

clear enough.”

I

bristled. “Meaning what?”

“I

didn’t see either of you at the orgy this morning. You spend a lot of time

together, just the two of you. You sleep together, yet you disdain sexual

relationships with the rest of your fellows. That isn’t how we like to do

things in Gentian Line.”

“You

Advocates keep yourselves to yourselves.”

“That’s

different. We have duties . . . obligations. Purslane wouldn’t understand

that. She had her chance to join us.”

“If

you’ve got something to say, why not say it to her face?”

He

looked away, to the brush-thin line of the horizon. “You did well with the

aquatics,” he said absently. “Nice touch. Mammals. They’re from . . .

the

old place,

aren’t they?”

“I

forget. What is this little pep talk about, Fescue? Are you telling me to keep

away from Purslane?”

“I’m

telling you to buck up your ideas. Start showing some

spine,

Campion.

Turbulent times are coming. Admiring sunsets is all very well, but what we need

now is hard data on emergent cultures across the entire Galaxy. We need to know

who’s with us and who isn’t. There’ll be all the time in the world for lolling

around on beaches after we’ve completed the Great Work.” Fescue poured the

remains of his wine into my ocean. “Until then we need a degree of focus.”