Threshold Resistance (15 page)

Read Threshold Resistance Online

Authors: A. Alfred Taubman

I was also comfortable with our breakfast because I had a clear understanding of and deep respect for our nation's important antitrust and fair trade laws and regulations. The Sherman Antitrust Act was no mystery to me. I had benefited from its enforcement.

Without such government intervention, specialty storesâthe lifeblood of my shopping centersâwould never have been able to compete with department stores for resources.

Back in the 1970s, when I was attending the annual convention of the International Council of Shopping Centers, I stopped in on a session about rents. I was floored to learn that developers were exchanging details of the leases they were signing with national retailers in their malls. When someone asked, “Hey, Al, what's the Gap paying you in your Bay Area centers?” I made quite a scene. I left the meeting, I told everyone about the illegality of their actions, and resigned from the ICSCâprohibiting participation by my companyâfor more than a decade. I am told this illegal sharing of information never happened again at an ICSC conference, in large measure because of my forceful protest.

I also understood the meaning of “conscious parallelism,” a concept in law that explains why it is acceptable for two gas stations on opposite corners of an intersection to offer gasoline at exactly the same price per gallon. Conscious parallelism also allows essentially every residential real estate broker in the country to charge sellers a 6 percent commission to market a home. As long as the parties do not reach an agreement to establish and hold to these prices, the fact that they arrive at the same price is okay with the law. If real estate brokers and gas station owners met to discuss pricing, that would go beyond conscious parallelism and enter the dangerous world of price-fixing.

Traditionally, Sotheby's and Christie's operated with identical commission schedules. That was nothing new. For decades, one house would adjust its rates for buyers and sellers, and the other would follow within weeks to stay competitiveâjust as the Shell station matches the Mobil station's price for unleaded within a few minutes of an adjustment. And they do it for the same reason: to stay competitive. I knew that it would be both unethical and illegal

to discuss pricing with Anthony Tennant or anyone else from Christie's (even though price-fixing was a civil, not criminal offense in the UK). So I welcomed Sir Anthony to my London flat on February 3, 1993, with tea, orange juice, scones, and a clear conscience.

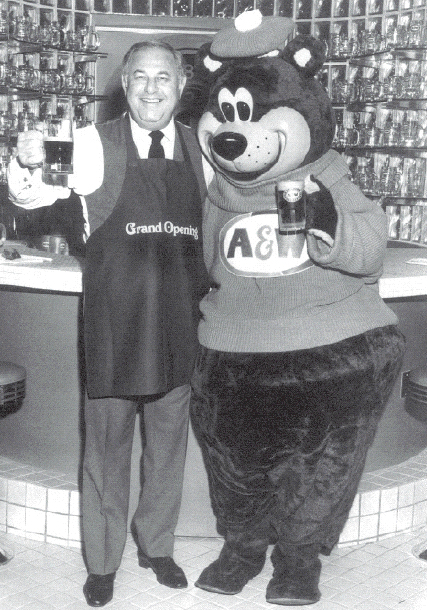

We exchanged pleasantries and discussed the fascinating art market for about an hour. Sir Anthony and I shared a deep respect for the Royal Academy, an expertise in marketing beverages (Guinness for him, A&W root beer for me), and a love for the English countryside. Beyond that, we had little in common. Unlike most of my British friends, Sir Anthony was not an avid sportsman and rarely went on shoots (a polite term for killing birds).

I remember an occasion in the late 1990s when I was walking through an exhibition of Audubon bird prints in Sotheby's New York galleries. Diana Phillips, head of our press office, came around the corner with a group of visiting art journalists. I took advantage of the occasion to opine as to the idiosyncrasies of the various feathered species illustrated on the prints.

One of the reporters asked, “Mr. Taubman, do you collect Audubon prints?”

“No,” I replied, “I don't think I have ever purchased an Audubon.”

“Then how is it that you have come to know so much about these birds?”

“I've shot every one of them.”

Diana abruptly terminated the impromptu interview and skillfully shepherded the journalists away.

When my breakfast discussion with Sir Anthony turned to the spirited and often underhanded competition between our two firms, I took a moment to explain the antitrust laws under which we operate in the United States. Sir Anthony, no stranger to international business, agreed immediately with my insistence that we stay far away from the subject of pricing. That was off the table.

Instead, we agreed that things like bad-mouthing each other in the press, misstating market share, poaching each other's experts, and not following regulations regarding the disclosure of guarantees (a practice we at Sotheby's referred to as “Christie's guarantees”) were damaging to both companies and our clients. On a more positive note, we agreed to work together to open the lucrative French market to international auction houses. Because neither Sotheby's nor Christie's was a French company, neither could conduct auctions in France. Political support for this arcane prohibition had been fading, and we had operated an office in Paris for yearsâa major investmentâto demonstrate our commitment to France and keep pushing for change. Christie's had not been as active, and I made it clear to Sir Anthony that we would appreciate their help.

I suppose if Christie's and Sotheby's had formed a trade association for international auction companies, we would have been discussing the same subjectsânot in my flat, but in a hotel conference room with PowerPoint presentations and lousy food. Looking back, that certainly would have been smarter for both of us. In the absence of such an organization, Sir Anthony and I met intermittently in London and New York over the next several years. Twelve times in four years, to be exact. Sir Anthony called my office every time to set these up. I never called him. Not once. I must admit that after the first few meetings, I really did not understand why he found the sessions useful. I certainly didn't. Oh, they were pleasant enough, but we had little to talk about (other than the Royal Academy's programs and strategies to overcome political threshold resistance in France).

I would brief Dede Brooks on my discussions with Sir Anthony, and he informed me that he was briefing Christopher Davidge as well. There was no reason to keep our thoughts from them, and with several issues it was important that they follow through on our understandings. For example, our agreement to tone down the public

bad-mouthing between the two companies would have been pointless without the CEOs passing our notice of détente on to the troops.

Now, I do not pretend to know what Sir Anthony and Christopher Davidge talked about in reference to these meetings. I do know, however, what Dede and I discussed. And never once did we address the subject of pricing or commissions in this context. It hadn't come up in my meetings with Sir Anthony, so there was no reason to re-hash the issue with Dede. Nevertheless, Dede and Davidge at some point (allegedly in 1995, almost two years after my first breakfast with Sir Anthony) decided to go well beyond the legitimate subjects Christie's chairman and I discussed. They proceeded to collude on the setting of new, nonnegotiable commission schedules for sellers at both houses. Dede participated in this illegal act without my knowledge, and certainly without my instructions.

When caught by the authorities in 2000 (and confronted with the fact that her accomplice, Davidge, would testify against her) Brooks would insistâafter a number of rejected proffersâthat she had been directed by me to break the law. Cleverly, she and Davidge would use the meetings between Sir Anthony and me as proof of my involvement. Certainly, one did not necessarily lead to the other. But the mere existence of the meetings (which I readily admitted to and documented in the voluminous personal diaries and daily office records I turned over to authorities) provided an enticing nexus for the perpetrators looking for an out and the prosecutors looking for a trophy to hang on their wall.

So on the evening of March 10, 1994, as the Scots Guards were marching and the trumpets were sounding in celebration, storm clouds were gathering high above New Bond Streetâclouds as dark and ominous as any the company had weathered in its illustrious 250 years. The forecast didn't look too promising for me, either.

T

he headline on the front page of the January 29, 2000,

Financial Times

changed a lot of lives around the world: “Christie's Admits Fixing Commissions: Auction House Tells the U.S. Justice Department That It Made Deal with Sotheby's.” A photograph of Dede Brooks accompanied the story.

The shocking revelation hit on a Saturday, the day I was celebrating my seventy-sixth birthday in Palm Beach. I heard the news for the first time from my friend art dealer Bill Acquavella, when he and his wife, Donna, arrived at my home that evening for the dinner party Judy had arranged.

“Al, have you heard what's going on? Christie's is admitting to price-fixing with Sotheby's,” Bill announced in a low, concerned voice. “It's front-page news in the

Financial Times.”

I remember being shocked and thinking how irresponsible it was for a respected publication to print such an accusation that was so inaccurate and, for Christie's, self-serving. Impossible. Inconceivable. The U.S. Justice Department had been investigating the art market since 1997, but the consensus was that the probe was going nowhere. And besides, we would never make such a “deal” with Christie's, our archrivals. I know I didn't. And certainly Dede, one of the most

competitive people I had ever met, would not have anything to do with such an illegal and destructive arrangement.

My first thought was that those bastards at Christie's, which had been acquired by a private French company in 1998 must have been nailed by the U.S. Justice Department in something sinister and were now throwing false charges at Sotheby's, a publicly held American company, to damage us and negotiate a lesser penalty. I called Dede the next day to hear what she knew about this mess. Instead, I got her husband, who explained that Dede would not be able to speak with me. That's when I really started to be concerned.

Early the next week, I kept a previously arranged appointment with Dede to discuss other matters. When I arrived at our headquarters at 1334 York Avenue, Sotheby's respected in-house general counsel, Don Pillsbury, accompanied me to Dede's conference room, where we could meet in his presence. He thought it best that he sit in on our conversation. Given the circumstances, I agreed. Dede assured us that there was no truth to the charge that Sotheby's had fixed prices with Christie's. She dismissed the

Financial Times

story with subdued confidence. I felt much better hearing her denials.

To break the tension, I held up a copy of the

Financial Times,

pointed to the headline, and said, “I don't think I'd look good in stripes!” (Later in court, testifying under oath, Dede would twist this story to say I had threatened her by saying

she

would look good in stripes. Don Pillsbury testified to the accuracy of my account, but no perjury charges were ever brought against Dede, the government's star witness.) The lighthearted aside, which prompted nervous but audible laughter from Dede and Don, was intended to dismiss the unthinkable outcome of my going to jail. I was relieved to hear Dede's assurances that there was nothing to worry about.

When we met about a week later at my home in Palm Beach, Dede again failed to come clean. She acted as if it were business as usual with Don, Max Fisher, Jeff Miro (on the phone), and me, and

left the meeting early to fly to Paris on business. What she didn't tell us was that she had arranged an unauthorized meeting to offer the company for sale to Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH Moët HennessyâLouis Vuitton. Arnault had recently acquired Phillips, a second-tier London-based auction house. Years earlier, Arnault had inquired through his bankers if we were interested in selling Sotheby's. He visited with me in New York and made a verbal offer for my shares. I informed Dede of Arnault's offer, and she encouraged me not to sell, insisting that Sotheby's stock was worth $100 per share. I turned him down, and the discussions never went beyond that preliminary, exploratory stage. Evidently, Dede, acting on her own, felt the time was right to rekindle Arnault's interestâjust as the U.S. Justice Department was preparing to charge us with price-fixing!

Over the next few days, it became clearer that Dede had indeed conspired with Christie's CEO, Christopher Davidge, and was prepared to testify that she had done so on my orders. While I knew these charges against me were false, there was mounting pressure on the company for me to step down as chairman. As much as it hurt me to take this step, which I was concerned would be misinterpreted by the board, employees, and the Justice Department as an admission of guilt, I agreed to resign my post. Dede stepped down from her position on the same day, February 21, 2000. Bill Ruprecht, who had worked his way up at Sotheby's through expert, marketing, and senior management positions, stepped in as president and chief executive officer. (He has done a terrific job guiding the company back to strength and profitability.)

At the time, I considered firing everybody on the board (as majority owner, I could technically do that) when they lost confidence in my innocence and me. Who the hell did they think they were? They knew my character. Isn't everybody innocent until proven guilty?

My wonderful parents, Fannie and Philip

A steel crew taking a break on a Federal's Department Store site in Detroit in the mid-1950s. I'm the young guy with the fancy hat seated in the center of the first row.

This September 4, 1971 issue of

Business Week

focused on the wave of regional mall development in America. I was lucky enough to be featured on the cover.

I designed this innovative (for the 1960s) fascia treatment for Max Fisher's Speedway 79 gas station chain. We created what was, essentially, a large plastic light box along the front of the service station using just-introduced outdoor fluorescent lighting. Motorists took notice, and Max became my lifelong friend.

The closing of our Irvine Ranch acquisition in 1977. Joan Irvine Smith is seated in the center, and Milton Petrie is the first gentleman standing on the left. Next to him is Don Bren, and second from the right is Herbert Allen.

That's the Great Root Bear on the right. I've been told there is a striking resemblance.

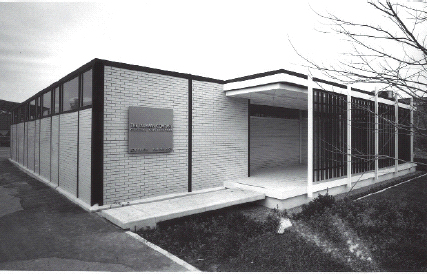

I designed The Taubman Company's office building in Oak Park, Michigan, which served as our headquarters from 1955 to 1968.

Ed Hoffman of Woodward and Lothrop, Taubman Company president Bob Larson, and me visiting a shopping center in the mid-1980s.

The Wall Street Journal

was the first to shorthandâand in the process distortâthe intended message of a speech I delivered to the Harvard Business School in 1985. Regrettably, “selling art is like selling root beer” became my slogan and was repeated (and often defended) by journalists around the world despite my best efforts to correct it, or at least place it in context.

This ancient Persian fabric bazaar effectively illustrates the fact that enclosed shopping centers were not invented in the twentieth century. Note the center-court fountain, the skylight, and the corridors housing multiple shops. Sketch in a Starbucks, and you'll have a great- looking contemporay mall.

I went in front of the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in London in 1983 to share my vision for Sotheby's. They approved and we acquired the venerable auction house soon after.

Dede Brooks and I posed for this photograph during the renovation of Sotheby's New York office and auction facility on York Avenue. The sparks flying in the background were a sign of things to come.